Menu

“Hydrostatic hydraulic pressure” isn’t a standard technical term in fluid mechanics. This phrase conflates two distinct concepts: hydrostatic pressure (the pressure exerted by a stationary fluid due to gravity) and hydraulic pressure (the pressure applied by pumps or pistons in hydraulic systems). Understanding the difference between these two types of fluid pressure is essential for applications ranging from basement waterproofing to industrial machinery design.

Hydrostatic pressure refers specifically to the pressure created by a fluid at rest under the influence of gravity. This pressure increases linearly with depth because more fluid weight accumulates above any given point.

The formula for calculating hydrostatic pressure is straightforward:

P = ρgh

Where:

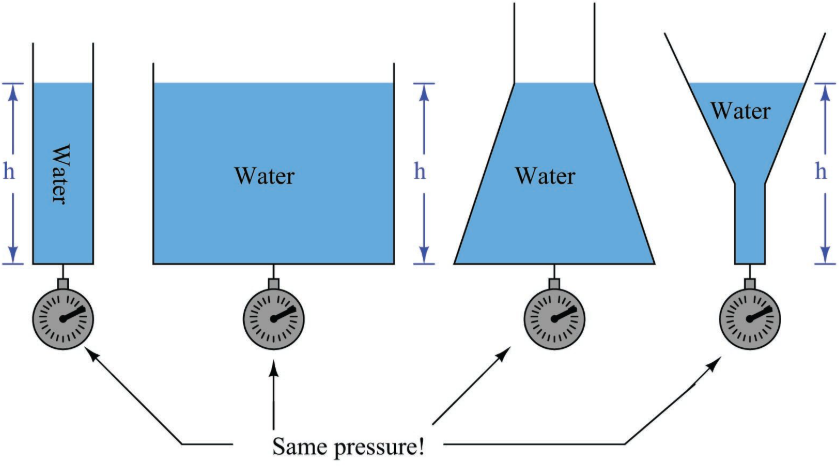

This relationship reveals a crucial characteristic: hydrostatic pressure depends only on depth, density, and gravity—not on the shape or volume of the container. A tall, narrow column of water and a wide, shallow reservoir exert identical pressure at the same depth, a phenomenon known as the hydrostatic paradox.

Unlike solid objects that exert force in one direction, fluid pressure acts equally in all directions at any given depth. This isotropic nature means that hydrostatic pressure pushes perpendicular to any surface it contacts—not just downward. A vertical wall submerged in water experiences horizontal pressure from the fluid, which is why dams must be engineered to withstand massive lateral forces.

Pascal’s Law, formulated by Blaise Pascal in 1647, describes this behavior: any change in pressure applied to an enclosed fluid transmits uniformly throughout the fluid in all directions. This principle underlies countless applications, from hydraulic brakes to deep-sea submersibles.

Hydrostatic pressure affects numerous everyday situations. Scuba divers experience approximately 1 additional atmosphere of pressure (14.5 psi or 1 bar) for every 33 feet (10 meters) of depth they descend. Concrete basement walls face hydrostatic forces when the surrounding soil becomes saturated with groundwater, potentially leading to structural damage or water infiltration. Underground storage tanks must account for soil moisture pressure to prevent deformation.

In medicine, hydrostatic pressure plays a vital role in capillary function. At the arteriolar end of capillaries, hydrostatic pressure (typically around 35 mmHg) exceeds osmotic pressure, forcing plasma and nutrients into surrounding tissues. This pressure differential facilitates nutrient delivery and waste removal at the cellular level.

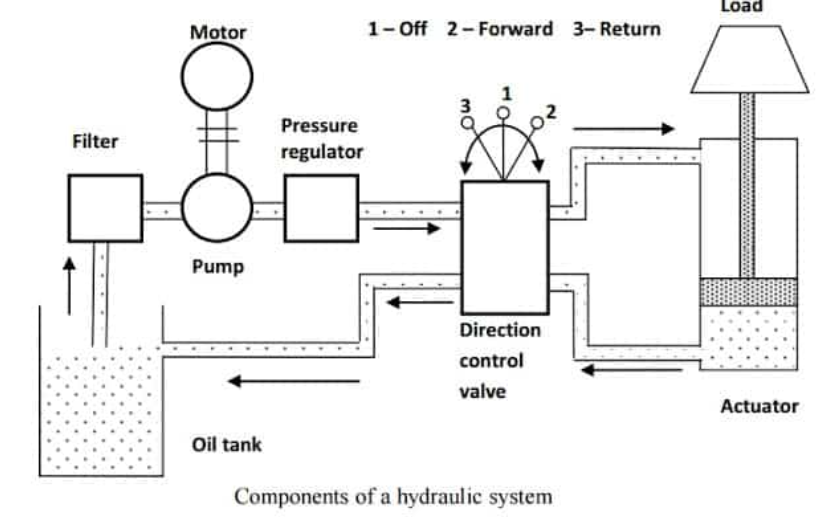

Hydraulic pressure, by contrast, is pressure generated by mechanical means—typically pumps, pistons, or motors—within a hydraulic system. This pressure enables force transmission through incompressible fluids to perform work.

Several characteristics separate hydraulic systems from hydrostatic conditions:

Active vs. Passive Generation: Hydrostatic pressure arises passively from fluid weight under gravity. Hydraulic pressure requires active mechanical input to create and maintain pressure.

Motion vs. Stillness: Hydrostatic principles apply to fluids at equilibrium with no flow. Hydraulic systems involve fluid movement, though the incompressibility of liquids allows near-instantaneous pressure transmission.

Purpose and Application: Hydrostatic pressure is a natural phenomenon that engineers must accommodate or mitigate. Hydraulic pressure is deliberately created to amplify force and perform mechanical work.

Modern hydraulic systems exploit Pascal’s Law through a different mechanism. When force is applied to a small piston in a hydraulic system, the resulting pressure distributes uniformly throughout the fluid. A larger piston elsewhere in the system experiences this same pressure across its greater surface area, producing proportionally greater force.

This force multiplication makes hydraulic systems invaluable for heavy machinery. A small input force can generate enormous output forces—excavators lift thousands of pounds, hydraulic presses shape metal with pressures exceeding 10,000 psi, and aircraft brake systems convert pedal pressure into wheel-stopping force.

Industrial applications distinguish between hydraulic and hydrostatic transmission systems based on pump design. Fixed-displacement hydraulic pumps move a constant fluid volume per revolution, generating continuous pressure when driven. Variable-displacement hydrostatic pumps adjust their output, providing

more precise control and efficiency by pumping only the volume needed.

This distinction matters for machinery design. Construction equipment with hydrostatic drive systems offers smooth speed control without mechanical transmissions. Agricultural tractors use hydrostatic pumps for infinitely variable speed adjustment. The terminology can be confusing since all hydrostatic transmissions are technically hydraulic systems, but not all hydraulic systems use variable-displacement (hydrostatic) pumps.

Although hydrostatic and hydraulic pressures differ in origin and application, they occasionally interact in engineering scenarios.

In a sealed hydraulic system, fluid at rest exhibits hydrostatic pressure distribution based on height differences between components. When the system activates, hydraulic pressure from the pump adds to or overcomes these existing hydrostatic pressures. Engineers must account for both when designing vertical hydraulic systems, such as elevators or multi-story manufacturing equipment.

Drilling operations provide a practical example of this interaction. Drilling mud circulates through the well bore to remove cuttings and prevent blowouts. The mud column creates hydrostatic pressure that must exceed formation pressure to prevent oil or gas influx. Simultaneously, pumps generate additional hydraulic pressure to circulate the mud. Operators must calculate both components to maintain safe drilling conditions.

Hydrostatic testing uses water (creating hydrostatic pressure) to verify the integrity of pressure vessels, pipelines, and hydraulic components. Test procedures pressurize systems beyond normal operating pressures using pumps (hydraulic pressure generation) while monitoring for leaks or failures. This application deliberately combines both pressure types: the test medium’s weight contributes hydrostatic pressure while pumps add hydraulic pressure to reach test levels.

The phrase “hydrostatic hydraulic pressure” likely emerges from several sources of confusion about fluid mechanics.

Construction and waterproofing professionals often use “hydrostatic pressure” broadly to describe any water pressure problem affecting structures. When discussing basement flooding caused by saturated soil, they might say “hydrostatic pressure from groundwater,” even though the water may be slowly moving (making it technically hydrodynamic pressure) or subject to additional forces from swelling clay soils.

Similarly, mechanical engineers might refer to “hydraulic testing” when they mean hydrostatic testing—using water to pressure-test equipment. The reverse confusion also occurs, with people calling pump-generated pressure “hydrostatic” because a liquid is involved.

The hydrostatic paradox—that pressure at a given depth is independent of container shape—sometimes leads people to believe that volume doesn’t matter. While true for pressure calculation, the total force on a surface does depend on surface area. A dam holding back a deep, narrow reservoir experiences the same pressure at its base as one holding a vast, shallow lake at equal depth, but the total force differs dramatically because the surface areas differ.

Pascal’s Law states that pressure change transmits uniformly through fluids, leading some to confuse pressure transmission with pressure generation. Hydrostatic pressure generates from fluid weight; hydraulic pressure generates from mechanical input. Both transmit according to Pascal’s Law, but their origins differ fundamentally.

Foundation design must account for hydrostatic pressure from the water table. Soils below the water table exert both lateral earth pressure and water pressure on retaining walls and basement structures. Modern construction addresses this through drainage systems (French drains, weep holes), waterproof membranes, and structural design that withstands combined loads.

Dams represent perhaps the most dramatic application of hydrostatic principles. The Hoover Dam’s base concrete endures hydrostatic pressures exceeding 45,000 pounds per square foot from Lake Mead’s 500-foot depth. Dam engineers use triangular cross-sections because hydrostatic pressure increases linearly with depth, requiring more structural mass at lower elevations.

Hydraulic systems dominate heavy industry because they provide high force density—substantial force from relatively compact components. Injection molding machines use hydraulic pressure exceeding 20,000 psi to force molten plastic into molds. Metal forming presses generate forces measured in thousands of tons through hydraulic cylinders.

Industrial robots increasingly use hydraulic actuation for applications requiring high force or operating in harsh environments. The incompressibility of hydraulic fluid provides rigid position control despite varying loads.

Submarines must withstand enormous external hydrostatic pressure while maintaining near-atmospheric internal pressure. At 800 meters depth, external pressure reaches approximately 80 atmospheres (1,176 psi). Hull design, viewport engineering, and penetration seals all account for this pressure differential.

Remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) for deep-sea exploration face even greater challenges. The Mariana Trench, at nearly 11,000 meters depth, imposes hydrostatic pressures exceeding 1,000 atmospheres. ROV hydraulic systems must function under these conditions, with pressure-compensated housings preventing system failure.

Blood pressure measurement relies on hydrostatic principles. When a blood pressure cuff inflates on the upper arm, hydrostatic pressure from the heart’s pumping action opposes the external cuff pressure. The height difference between the heart and measurement site affects readings—blood pressure measured at the ankle differs from arm measurements due to the additional fluid column height.

Capillary filtration and absorption depend on the balance between hydrostatic pressure (pushing fluid out) and oncotic pressure from plasma proteins (drawing fluid in). Disruptions in this balance lead to edema. Congestive heart failure increases venous hydrostatic pressure, forcing excess fluid into tissues.

High hydrostatic pressure (HHP) processing has emerged as a non-thermal food preservation method since its commercialization in the 1990s. Foods packaged in flexible containers undergo pressures of 400-600 MPa (58,000-87,000 psi) for several minutes. This pressure inactivates pathogens and spoilage organisms while preserving nutritional content and fresh characteristics better than heat pasteurization.

The global HHP market has grown substantially, with applications including cold-pressed juices, guacamole, deli meats, and seafood. Recent research explores combining HHP with biopreservatives for enhanced food safety, with particular growth in Asian and European markets where consumers demand minimally processed foods.

Different industries use various pressure units, sometimes causing confusion:

For water, a useful approximation is that every 10 meters of depth adds roughly 1 bar (or 1 atmosphere) of hydrostatic pressure. More precisely, freshwater at 4°C has a density of 1000 kg/m³, yielding approximately 98.1 kPa (0.981 bar) per 10 meters.

Several variables influence real-world pressure calculations beyond the basic hydrostatic formula:

Fluid Density Variation: Temperature and dissolved substances alter density. Seawater (density ≈ 1025 kg/m³) generates slightly more pressure than freshwater at equal depths. Hot fluids exert less pressure than cold ones due to thermal expansion reducing density.

Atmospheric Pressure: Open systems must add atmospheric pressure to hydrostatic pressure for total (absolute) pressure calculations. At sea level, atmospheric pressure contributes approximately 101.3 kPa. Gauge pressure readings exclude atmospheric pressure, measuring only pressure above atmospheric.

Compressibility: The hydrostatic formula assumes incompressible fluids, valid for liquids under most conditions. Gases, however, compress significantly under pressure, requiring different calculation approaches. Even water becomes slightly compressible at extreme depths—ocean bottom pressures reduce water volume by about 1.8%.

Designing hydraulic systems requires calculating required pressures, flow rates, and component capacities. The force available from a hydraulic cylinder equals pressure multiplied by piston area:

F = P × A

Where F is force (Newtons), P is pressure (Pascals), and A is piston area (m²). A cylinder with a 5 cm diameter piston (area ≈ 0.00196 m²) operating at 10 MPa (100 bar) can theoretically generate 19,600 N (approximately 4,400 pounds-force).

Flow rate requirements depend on desired actuation speed and cylinder volume. Pump capacity, measured in liters per minute (LPM) or gallons per minute (GPM), must exceed maximum system flow demand while maintaining pressure.

Uncontrolled hydrostatic pressure poses several risks:

Structural Failure: Buildings constructed without proper drainage or waterproofing can experience foundation cracking, basement wall bowing, and floor heaving when groundwater levels rise. Retaining walls without adequate drainage may overturn or slide as water pressure builds behind them.

Flotation: Empty underground storage tanks or swimming pools can float out of the ground when the water table rises, creating hydrostatic uplift forces exceeding the structure’s weight. This phenomenon has lifted swimming pools several feet above ground level after heavy rainfall.

Diving Accidents: Rapid ascent from depth without proper decompression allows dissolved gases in blood and tissues to form bubbles as ambient pressure decreases, causing decompression sickness (the bends). Pressure-related injuries also include barotrauma affecting air spaces in ears, sinuses, and lungs.

High-pressure hydraulic systems present distinct hazards:

Fluid Injection Injuries: Hydraulic fluid escaping through small leaks under high pressure can penetrate skin, causing serious tissue damage. Pinhole leaks are particularly dangerous because the high-velocity jet is nearly invisible but can inject fluid deep into tissue, requiring immediate medical treatment.

Hose and Component Failure: Hydraulic hoses eventually degrade from pressure cycling, temperature exposure, and abrasion. Catastrophic hose failure can spray hot hydraulic fluid at high velocity, causing burns and injuries. Regular inspection and replacement per manufacturer specifications prevents such failures.

System Over-Pressurization: Pressure relief valves protect hydraulic systems from over-pressurization that could damage components or cause explosions. These valves must be properly sized, regularly tested, and never blocked or bypassed.

Fire Hazards: Hydraulic fluid mist from high-pressure leaks can ignite when exposed to heat sources. While petroleum-based hydraulic fluids are not highly flammable, fine mists are. Fire-resistant fluids exist for applications near ignition sources.

Both hydrostatic and hydraulic systems require regular testing to ensure safety:

Hydrostatic Pressure Testing: Pressure vessels, pipelines, and firefighting equipment undergo periodic hydrostatic tests at pressures exceeding normal operation (typically 1.5× to 2× design pressure). These tests verify structural integrity and reveal leaks before equipment enters or returns to service. Testing standards from ASME, DOT, and other regulatory bodies specify test procedures, durations, and acceptance criteria.

Hydraulic System Maintenance: Proper maintenance extends system life and prevents failures. Critical tasks include fluid analysis (checking for contamination and degradation), filter replacement, hose inspection, seal replacement, and pressure setting verification. Many industrial facilities implement condition-based maintenance using vibration analysis, thermography, and fluid sampling to detect problems before failures occur.

Modern materials and engineering enable structures to operate at remarkable depths. Commercial submarines typically operate at 200-400 meters depth (20-40 atmospheres), though military vessels may dive deeper. The pressure hull of a submarine at 400 meters depth must withstand approximately 40 bar (580 psi) of external pressure difference. Scientific research submersibles have reached the Mariana Trench bottom at nearly 11,000 meters, where pressure exceeds 1,000 bar (1,100 atmospheres or 16,000 psi). These deep-diving vehicles use titanium or specialized steel alloys with spherical pressure hulls, the shape most efficient for resisting external pressure.

Yes, with appropriate engineering. Underwater hydraulic systems are common in offshore drilling, ROVs, and subsea production equipment. These systems use pressure-compensated reservoirs that allow the hydraulic fluid to equilibrate with ambient water pressure, preventing housing collapse while maintaining pressure differential for actuation. In space, hydraulic systems face challenges from temperature extremes and lack of gravity for fluid management, but they remain viable. The Space Shuttle used hydraulic systems for flight control surfaces and landing gear, with heaters and accumulators managing fluid behavior in vacuum and microgravity.

Concrete has excellent compressive strength but relatively weak tensile strength (typically 8-15% of its compressive strength). Hydrostatic pressure creates bending forces in foundation walls that put one side in compression and the other in tension. When tensile stresses exceed concrete’s tensile strength, cracks form. Additionally, concrete is porous, allowing water to penetrate through capillary action. If this water freezes, the expansion generates internal pressure exceeding concrete’s tensile capacity, causing spalling and cracking. Proper foundation design includes reinforcing steel to resist tensile forces, waterproof coatings or membranes, and drainage systems to manage groundwater and prevent hydrostatic pressure buildup.

High-pressure hydraulic oil presents serious safety hazards. Even small leaks can inject fluid through skin into underlying tissue, causing severe injury that may lead to amputation if untreated. These injection injuries occur when workers check for leaks by passing their hands near pressurized lines—the fluid jet can be invisible but capable of penetrating skin. Modern hydraulic systems operate at 2,000-5,000 psi (140-350 bar), with some industrial applications exceeding 10,000 psi (690 bar). At these pressures, even a pinhole leak creates a fluid jet capable of injection injury. Safety protocols require using cardboard or paper to detect leaks, never bare hands. Additionally, hydraulic fluid mist from high-pressure leaks can ignite near heat sources, and hot hydraulic fluid can cause severe burns.

While “hydrostatic hydraulic pressure” combines two distinct fluid mechanics concepts, understanding both types of pressure is essential across engineering disciplines. Hydrostatic pressure from gravity-driven fluid weight requires structural accommodation and drainage management. Hydraulic pressure from mechanical systems enables force amplification for countless industrial applications. Both obey Pascal’s Law for pressure transmission but differ fundamentally in generation and purpose. Modern engineering successfully manages and exploits these pressure types through proper design, testing, and maintenance practices.

Recommended Internal Links