Menu

I’ve been working with hydraulic systems since 2008. Back then I was doing maintenance work at a steel plant in Ohio, changing out valves on a continuous casting line. Nobody told me there were different ways to mount these things. I learned by making mistakes.

Over the years I’ve installed probably 3,000+ valves across maybe 40 different machines. Press brakes, injection molding machines, mobile equipment, you name it. I’ve seen installations that lasted 15 years without a single leak. I’ve also seen brand new setups that failed within a week because someone picked the wrong connection method for the application.

This is what I’ve learned about each approach.

The most common type you’ll see on smaller valves. Anything under 3/4 inch port size, you’re probably looking at threaded fittings. NPT in North America, BSPP in Europe and most of Asia.

I used to think threaded connections were inferior. They’re not. For low-flow applications under 2000 PSI, a properly installed threaded valve will outlast the machine it’s mounted on. The key word is “properly installed.” I’ve watched guys crank down on fittings with a 24-inch pipe wrench until the housing cracked. Aluminum valve bodies don’t appreciate that kind of treatment.

Thread sealant matters more than most people realize. I switched from Teflon tape to anaerobic sealant (Loctite 545, specifically) around 2014 after dealing with a recurring leak on a hydraulic power unit. The tape kept shredding and contaminating the system. Took me three filter changes to figure out where the debris was coming from.

The downside with threaded ports is serviceability. Every time you remove a valve, you’re potentially damaging the threads. On a machine that needs frequent valve changes, you’ll eventually wear out the port threads in the manifold or cylinder. I’ve seen this happen on test stands where valves get swapped out weekly.

Some old-timers at the steel plant called these “all five organs complete” valves. Everything is built into one housing. Inlet, outlet, control mechanism, mounting points. You bolt it directly into the hydraulic line and it handles everything on its own.

I don’t see these as much on newer equipment. They were popular in the 1990s on simpler machines. The main advantage was simplicity. No subplates, no manifolds, no additional mounting hardware. The valve body itself was the entire assembly.

The limitation is flexibility. When one component inside fails, you replace the whole unit. On a packaging machine I serviced in 2012, the relief section of an inline valve went bad. Had to swap the entire valve because there was no way to rebuild just that portion. Cost the customer about $800 more than it would have with a modular setup.

Mobile equipment uses these extensively. Excavators, loaders, agricultural machinery. The concept is straightforward. Each section controls one cylinder group. You stack as many sections as you need and bolt them together.

A guy I worked with on farm equipment in Iowa explained it simply. One section runs the boom, another section runs the bucket, another section runs the swing. If the bucket section fails, you unbolt that one section and replace it. The rest of the stack stays in place.

I’ve only worked on a handful of sectional setups. They’re common in mobile hydraulics but rare in industrial applications. The manufacturers design them specifically for equipment where operators need proportional control of multiple functions through joysticks or levers.

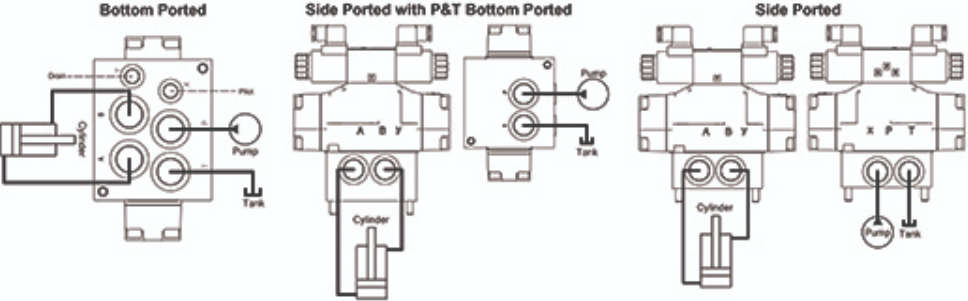

This is where the valve bolts to a machined plate (the subplate), and the subplate has all the port connections. The valve seals to the subplate through O-rings in a standardized bolt pattern. The old hands used to say the valve needs its own “shoes” to stand on. The subplate is those shoes.

CETOP (European) and NFPA (North American) patterns are the two standards. They’re not interchangeable, which has caused problems on machines built overseas and shipped to the US. I got called to a plant in 2020 where they’d ordered replacement valves without checking the mounting pattern. The new valves showed up with CETOP-03 patterns and the subplates were NFPA D03. Same general size, completely different bolt spacing.

The advantage of subplate mounting is that you can change valve brands without replumbing. If your Vickers valve fails and the distributor only has Eaton in stock, you unbolt one and bolt on the other. The hydraulic connections stay put.

Leak points multiply with this approach. You’ve got O-rings between the valve and subplate, plus whatever connections are on the subplate itself. Each interface is a potential failure point. On a system I troubleshot in 2017, a slow leak had been attributed to a worn valve spool for months. Turned out to be a deteriorated O-ring on the subplate that only leaked when the oil got above 140°F.

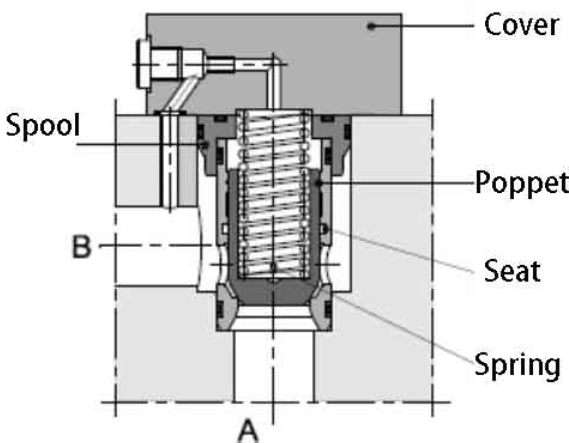

Cartridge valves that thread or drop into a machined aluminum or steel block. All the flow paths are internal. You might have 6, 8, 12 valves in a single manifold with only the main pressure and tank lines coming out. The manifold is like the “pants” that holds everything together. Without it, cartridge valves have nowhere to go.

This is the cleanest installation method. Minimal external plumbing means fewer leak points and less chance of hose failure. The systems I’ve built with integrated manifolds have the lowest callback rate of anything I’ve done.

The problems come later. When a valve fails inside a manifold, diagnostics get complicated. Is it the pressure relief? The directional valve? The flow control? You can’t see anything. I spent an entire day in 2021 chasing an intermittent fault on a CNC machine that turned out to be a check valve sticking inside the manifold. No external symptoms. Oil analysis was clean. Pressure readings looked normal until they didn’t.

Custom manifolds also mean long lead times. Four to eight weeks from most suppliers. When a manifold cracks or gets damaged, the machine is down until the replacement arrives. I keep telling customers to order a spare manifold when they buy the machine. Most don’t listen until they’ve lost a week of production waiting for one.

These have grown in popularity over the past decade. Smaller than slip-in cartridges, they thread directly into a cavity in the manifold. The development started in European mobile equipment and spread into industrial applications around 2010.

The weakness is the thread engagement area. High pressure cycles stress the threads repeatedly. I’ve seen cavities in aluminum manifolds strip out after 3 or 4 years of heavy use. The countermeasure most manufacturers recommend now is steel thread inserts or specifying steel manifolds for high-cycle applications. Adds cost but extends service life considerably.

Standardization is still catching up. Sun Hydraulics, Hydac, Bucher, they all have slightly different cavity dimensions for similar flow ratings. A replacement valve from a different manufacturer might not fit the existing cavity without modification.

It depends on the application. I know that’s not a satisfying answer.

For prototype machines and test fixtures where things change constantly, I use threaded fittings and accept the serviceability limitations. Speed matters more than longevity.

For production equipment that needs to run 20 hours a day, subplate mounting with standardized valve patterns. Maintenance crews can swap valves without calling an engineer.

For mobile equipment and compact machinery, manifold integration is usually the only practical choice. There’s just no room for anything else.

I got this wrong plenty of times early in my career. Spec’d cartridge manifolds on a test stand that needed daily valve changes. Designed a production machine with threaded connections that wore out within two years. These aren’t theoretical problems.