Menu

If you’ve been doing hydraulic component selection long enough, you know that when it comes to piston pumps, axial and radial types are two completely different worlds.

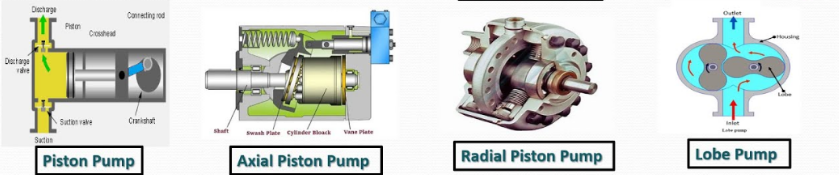

Axial piston pumps are everywhere. Open up an excavator, loader, or forklift, and nine times out of ten you’ll find a swashplate design inside. Bosch Rexroth, Kawasaki, Nachi—any of these manufacturers have their shelves stocked with this type. Variable displacement is convenient, response is fast, and spare parts are easy to find. Why does construction equipment universally use axial pumps? The reason is simple: flow rate is king, and hydraulic cylinder extension speed trumps everything else. For the same housing size, an axial pump can pack in more than double the displacement of a radial pump. A 250cc axial pump might only be as big as a 100cc radial pump.

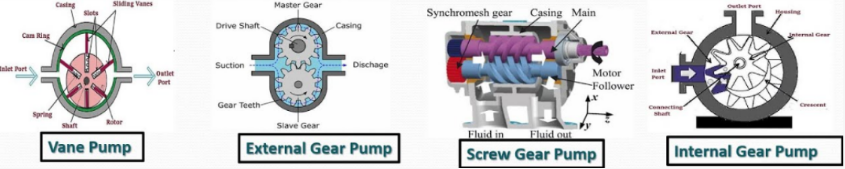

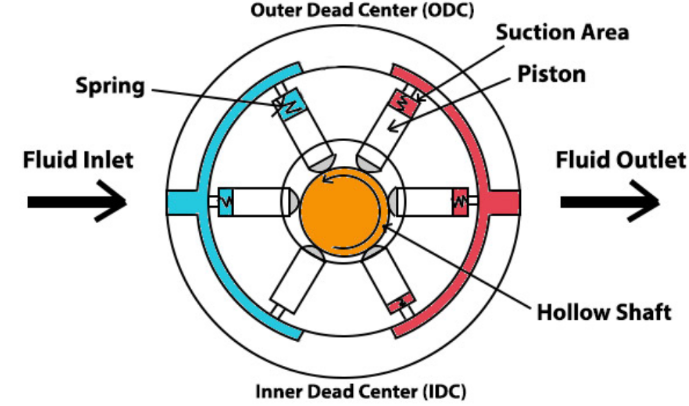

Radial piston pumps are much more niche. The pistons aren’t arranged along the shaft—they stick outward like wheel spokes. An eccentric cam rotates in the center, pushing the pistons outward, while springs pull them back. Oil intake and discharge are controlled by valves, not a port plate. This arrangement means they’re inherently disadvantaged in flow rate, but the design has other benefits.

What benefits? Pressure handling. Getting an axial pump above 350 bar requires premium materials and processes. The precision requirements for swashplate, port plate, and slipper pad mating surfaces are frighteningly tight, and costs climb accordingly. Radial pumps rely on their structure—force distribution is even, and side loading between pistons and cylinder bores is minimal. Some Hawe R-series models are rated up to 700 bar. Nobody actually pushes them that hard in real work, but they can technically reach those numbers. Moog’s RKP is rated at 350 bar continuous and 420 bar peak—different positioning, as they focus on servo control and low noise.

Speaking of Hawe, this German manufacturer has been making radial pumps for decades with an extensive product line. Their pumps use valve-controlled timing, with pistons arranged in a star pattern around an eccentric shaft. They can stack multiple layers, with the largest configurations fitting 42 pistons across 6 layers. Their technical documentation recommends 1450 rpm, and while higher speeds are possible—people have run them at 2800 or even 3600—service life takes a hit. They have an RG model with sleeve bearings, designed for harsh conditions or applications with shock loads.

Moog takes a different approach. The RKP series uses a sliding stroke ring to adjust displacement rather than valve timing. Displacement ranges from 19cc up to 250cc. This pump is well-known in the injection molding world. Plastics processing people are sensitive to noise—shops are already loud enough without pumps droning away. At one point, Moog changed the 63 and 80 size pump cores from 7 pistons to 9, claiming it reduced pressure pulsation and brought noise below 70 decibels. I haven’t heard it myself, but injection molding people definitely trust this brand.

Where’s the turf for radial pumps? Machine tool hydraulic systems are one area—cutting fluid delivery, hydraulic fixture actuation, and such. Test stands too, where long-term pressure stability is needed—radial pumps are well-suited. Also various clamping systems, press overload protection—anywhere you need pressure, not flow. Wind turbine pitch systems have started using radial pumps in recent years. There’s actually decent space inside the tower, flow requirements aren’t high, and pressure stability is what matters.

Pump failures are mostly due to dirty oil. This applies to radial pumps and axial pumps alike. Motion Industries, a major hydraulic repair company in North America, has statistics showing that 75% to 90% of pumps sent in for repair can be traced back to fluid contamination. Particles get in and score the piston surfaces, clearances open up, internal leakage increases, and pressure drops. From the outside, if the case drain line feels hotter than the outlet line, that’s a sign of serious internal leakage. Once leakage exceeds 10% of rated flow, it’s about time to replace the pump.

Another failure mode is pressure spikes breaking things. This is hard to prevent—it might only take a few milliseconds. A pressure spike hits, stress concentrates at the piston neck, and snap—it breaks. Control pins are also vulnerable; shear one and the pump is completely done. Regular pressure gauges can’t catch these transients. You’d need high-speed data acquisition equipment to really investigate. Most shops don’t have that kind of gear, so usually it’s only during post-failure autopsy that you find out what happened.

Selection isn’t rocket science—just list your requirements clearly. High pressure, low flow: consider radial. High flow with variable displacement: go with axial. For situations in between, ask multiple suppliers for proposals, then judge which one makes sense. There’s no universal pump—only the right pump for the job.