Menu

How does the hydraulic fluid circulate within the system? The flow path is crucial. In some systems, the hydraulic fluid flows continuously from the pump, through valves, and back into a large reservoir – even when the system is idle. In other systems, the fluid remains in a tightly sealed circuit between the pump and the actuator, with only a very small amount returning to the reservoir.

This fundamental difference separates open center hydraulic systems (also known as open circuits) from closed center hydraulic systems (closed circuits or hydrostatic systems). Manufacturers of equipment for construction, agriculture, mining, or factory automation often face this decision. It impacts efficiency, heat generation, component lifespan, response time, and overall cost. Each method handles loads, braking, and energy differently. Understanding the flow path helps explain why one approach is better suited for certain applications than another.

Open hydraulic systems utilize a simple design. The pump draws hydraulic fluid from the tank, directs it through control valves, and delivers it to cylinders or motors as needed. During idle operation, the hydraulic fluid flows freely back into the tank with minimal pressure increase.

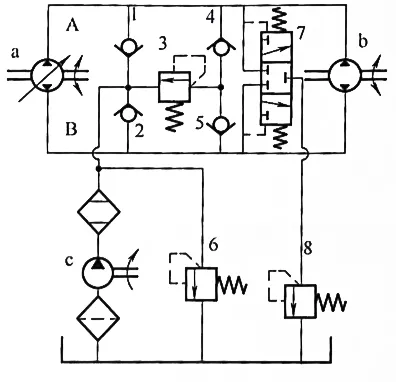

Below are typical diagrams of open hydraulic circuits:

The advantage of this design lies in its simplicity. The continuous fluid circulation helps cool the fluid, purges air, and allows contaminants to settle in the larger tank. Reversing is accomplished via valves, but insufficient valve overlap during rapid direction changes can lead to pressure spikes.

During braking or reversing, especially when using a hydraulic motor, the motor briefly acts as a pump due to inertia. Without an energy recovery mechanism, energy is lost as heat through the pressure relief valve. The same happens during lowering due to gravity – while counter-pressure components prevent uncontrolled acceleration, they also generate heat and consume energy.

Many diesel-powered mobile machines, such as loaders, excavators, and forklifts, use open center hydraulic systems. These are suitable for applications with low power requirements or where cost and ease of maintenance are paramount. Stationary systems with predictable cycles also benefit from this approach.

A closed hydraulic system, often also called a hydrostatic or closed-loop system, forms a direct circuit between the pump and the actuator. The oil flows from the pump to the motor or cylinder and then directly back to the pump inlet. A small charge pump handles leakage replenishment and cooling.

A typical closed-loop schematic includes a charge pump and a relief valve:

The direction is changed by the variable displacement of the pump – a separate valve is not required. This allows for smoother speed and direction control.

Braking is particularly important here. Since the inertia-driven actuator acts like a pump, it pressurizes the return line, thus recovering energy during deceleration. In motor-driven systems, this energy can be fed back into the grid. Gravity loads also benefit from this, as excessive speeds are prevented without significant energy loss.

The circuit remains largely sealed, allowing for smaller tank sizes and a compact design. However, limited oil exchange leads to a faster temperature increase, requiring careful filtration and cooling.

These systems are suitable for applications with high inertia, such as crane slewing or travel drives that require frequent start-stop operations. They are also suitable for compact mobile devices or precision machine tools with limited space.

When evaluating open and closed centering systems, the biggest differences lie in fluid management and energy management.

Open hydraulic centering systems achieve excellent heat dissipation through continuous circulation and large tanks. They eliminate the need for complex pump control, simplifying initial setup and facilitating maintenance. However, energy is lost during idle operation, and braking is dissipative.

Closed hydraulic centering systems minimize unnecessary flow rates, thus improving efficiency under variable load. Under high load and frequent cycles, energy recovery during braking can lead to significant energy savings. The compact design allows for installation even in confined spaces. Disadvantages include faster heat buildup and the increased complexity of components such as variable displacement pumps.

The pressure characteristics also differ. Open centering systems only build up pressure when needed and operate at lower pressure in standby mode. Closed centering systems maintain constant system pressure, resulting in faster response times but requiring more robust components.

For machines with multiple actuators, closed centering systems with load-sensing options are often better suited for the simultaneous execution of multiple functions.

In modern manufacturing, energy consumption is often the decisive point of contention between open and closed centering systems.

The continuous flow in open centering systems leads to higher idle losses, especially during prolonged operation. However, under moderate loads, the excellent cooling of the tank by air supply can largely compensate for these losses.

Closed centering systems reduce pumping effort during idle operation and thus lower energy consumption. In systems with high inertia, braking energy recovery is of great value. Compact tanks require more powerful coolers or filters for heat dissipation.

Many companies today are opting for closed-loop hydraulic systems to achieve energy savings. However, if simplicity is more important than slightly higher efficiency, open-loop systems remain the better choice.

In the summer of 2017, a small company in central Illinois upgraded the grain handling systems on its custom harvesting combines. The original configuration utilized an open-loop hydraulic system on a loader attachment for a grain transport vehicle.

Operators reported uneven and inconsistent lifting speeds when raising loaded booms, especially in high temperatures, as rising oil temperatures and decreasing viscosity exacerbated the problem. Multiple functions, such as simultaneous lifting and steering, competed for oil flow, leading to delays during peak season.

The team switched to a closed-loop hydraulic system with a variable displacement pump and load-sensing valves. A small oil replenishment circuit was also installed.

The results showed smoother lifting, more consistent speeds under varying loads, and reduced operator fatigue. Downtime during peak season was reduced, although the exact figures are proprietary and have not been independently verified.

This project illustrates how closed-loop systems can improve precision under variable agricultural loads, while open-loop systems suffice for basic tasks.

Such projects often raise questions about component selection. If you are experiencing similar issues, contact POOZOM for more information on hydraulic projects or to determine which system best suits your equipment configuration.

For specific flow or pressure requirements, custom hydraulic solutions can be considered. These solutions allow for the precise matching of components to either open-loop or closed-loop hydraulic system architectures.

Standard components are suitable in many situations, but stringent specifications often require custom solutions. Custom manifolds, pumps, or valves ensure an optimal fit, even in confined spaces.

Open systems are characterized by their simplicity: when the control valve is in the neutral position, the pump flow returns to the tank at low pressure.

Open systems are the industry standard for applications that do not require high power. Because they typically use fixed-displacement gear pumps, the initial capital expenditure (CAPEX) is significantly reduced. They are robust systems that do not require complex, multi-functional synchronization devices.

In the US rental and construction equipment market, machines such as mini-excavators or skid steer loaders rely on open hydraulic systems for intuitive operation.

Since the pump is directly coupled to the engine speed, the operator receives immediate haptic feedback. Furthermore, the continuous oil flow in the neutral position serves as an integrated thermal management circuit and ensures oil filtration and flow even during short idle periods.

In rural or remote locations across North America – from mines in Alaska to farms in the Midwest – ease of maintenance is paramount.

Open systems do not require complex compensators and sensing lines, as are common in closed systems. This means:

Closed systems (typically using load-sensing or LS technology) maintain system pressure at the valves but stop the flow when the control is in the neutral position.

For North American heavy industry, such as commercial fishing (winches) or heavy-duty transport (drive units), efficient momentum management is crucial.

“Regenerative” factor: As experts at Parker Hannifin emphasize, closed-loop control systems excel at energy recovery.

When heavy winches decelerate, the system can capture this energy or use it for precise load balancing, preventing uncontrolled load runaway and reducing heat generation.

Modern American agriculture requires tractors to handle steering, hitch leveling, and the operation of multiple hydraulic implements simultaneously.

Closed systems are particularly well-suited in this area because they allow for independent flow. One function does not compromise the flow of other functions due to lower pressure requirements, ensuring smooth and predictable multitasking operation.

With the increasing adoption of fluid power technology in the US, closed systems are becoming the preferred complement to electric motors.

Because the pump only delivers flow when needed, battery life is maximized and the carbon footprint is reduced. In manufacturing environments (mills/presses), the constant pressure allows for instantaneous response and sub-millimeter precision.

Variable vs. Constant Load: With constantly changing loads, a closed system’s ability to adapt to the load saves thousands of dollars in fuel/energy costs over the machine’s lifespan.

Simultaneous Operation: Does the operator need to perform lifting, tilting, and movement operations simultaneously? In this case, the flow distribution of a closed/load-sensing system is essential.

Heat Dissipation: In 24/7 operation, an open system can generate excessive heat due to pressure relief through the overflow valve. Closed systems operate at lower temperatures under high load, potentially allowing for the use of smaller and lighter cooling components.

On-site or workshop repair: Consider where the machine will be repaired. If it’s a machine that can be rented out directly and requires only basic mechanical knowledge to operate, an open-center system is sufficient. However, if it’s a high-performance production machine with a professional dealer network, a closed-center system is recommended.

Open and closed hydraulic systems offer proven solutions for power transmission. Open systems are characterized by simplicity, good cooling, and cost-effectiveness in straightforward applications.

Closed systems offer efficiency, compactness, and energy recovery for dynamic or precise operations.

Matching the system to the actual requirements—loads, environmental conditions, and objectives—ensures reliable performance in production operations. Both system types are continuously being further developed and equipped with improved pumps and controls.