Menu

We’ve been designing hydraulic systems for manufacturing equipment since 2009, and if there’s one component that gets overlooked until something breaks, it’s check valves. Last month, a customer called us because their CNC machine’s hydraulic clamping system kept losing pressure overnight. Three-hour troubleshooting session later, we found a $35 check valve with a worn poppet seat leaking just enough to drop 400 PSI over eight hours.

Check valve hydraulic circuits are everywhere in industrial equipment – injection molding machines, metal forming presses, mobile equipment, you name it. They’re simple devices: let fluid flow one direction, block it in the other. But the performance difference between a properly selected check valve and a cheap one you grabbed from the supply cabinet? That’s the difference between a machine that runs three shifts without issues and one that your maintenance team hates.

Most engineers learn hydraulic theory from textbooks that show perfect symbols on perfect schematics. Reality is messier. Pressure spikes, temperature swings, contamination – your check valves see all of it.

Take a typical vertical cylinder application. You’ve got a 3-inch bore cylinder holding a 2000 lb mold platen. When the cylinder extends and stops, you need that load to stay put during the molding cycle. A standard poppet check valve on the rod-end line prevents the platen from dropping. Simple enough. But what people don’t realize: that check valve is holding against dynamic forces during the injection phase, thermal expansion of the hydraulic oil, and any vibration from adjacent equipment. If your check valve has even slight reverse leakage – say, 0.5 cubic inches per minute – the platen drifts. Maybe just 0.010″ per hour. But after an eight-hour shift? Your mold parting line is off by 0.080″, and you’re making scrap parts.

We see this constantly with cheaper ball-style check valves. They cost $40 instead of $180 for a pilot-operated check, but the leakage rate is five to ten times higher. For a return line or drain circuit where slight leakage doesn’t matter, fine, use a ball check. For load holding, you need a proper pilot-operated check valve from someone like Parker (their CPOM series) or Eaton (VBCD line).

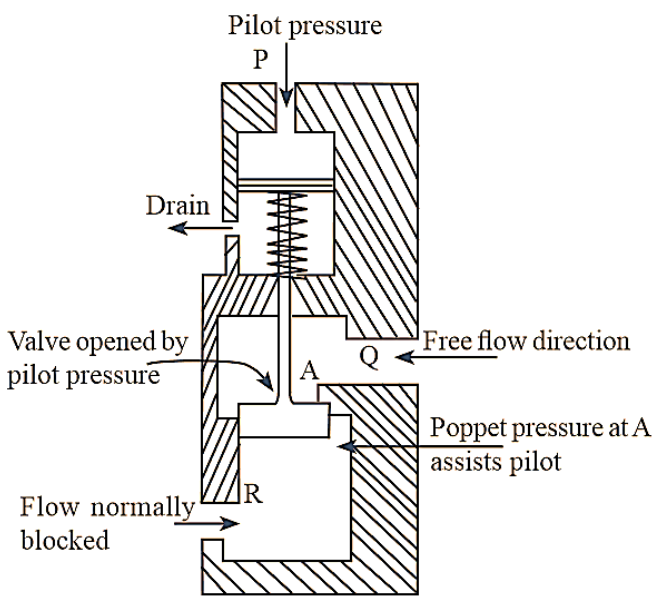

Speaking of pilot-operated checks: the pilot ratio matters more than most datasheets emphasize. A 4:1 ratio means you need 1000 PSI of pilot pressure to open a valve that’s holding 4000 PSI on the other side. Sounds straightforward until you’re trying to lower that vertical cylinder and your system pressure is only 3000 PSI. Suddenly you can’t generate enough pilot pressure to open the check valve smoothly. The cylinder jerks, starts and stops, drives the machine operator crazy. We usually spec 5:1 ratio valves for vertical applications because it gives more controllable lowering with less pilot pressure required.

Here’s something manufacturers don’t advertise clearly enough: every check valve creates pressure drop in the forward flow direction. Even after the valve cracks open, you’re still losing pressure pushing fluid through the valve. A Sun Hydraulics CP12 series check valve (1/2″ cartridge size) with 2 PSI cracking pressure will drop an additional 3-4 PSI at 8 GPM flow rate. Doesn’t sound like much. But if you’ve got four check valves in series through your circuit – pump outlet, branch line, cylinder port, maybe another for isolation – you’ve just lost 20+ PSI before you even do any work.

Twenty PSI might not stop your cylinder from moving, but it’s wasted energy that turns into heat. We measured this on a customer’s system last year: they had undersized check valves throughout a 30 GPM circuit. Total pressure drop from just the check valves: 65 PSI. That’s nearly 3 HP of wasted energy converted to heat. Their oil cooler was running constantly, and they couldn’t figure out why the system temperature kept climbing. We replaced five check valves with properly sized units (went from size 08 to size 12 cartridges), and their oil temperature dropped 15°F.

The flow coefficient (Cv) number in valve specifications tells you about pressure drop, but you have to dig for it. Bigger Cv means lower pressure drop at the same flow rate. For high-flow circuits – anything over 15 GPM – we typically won’t use a check valve with Cv below 4.0. The pressure drop penalty isn’t worth the cost savings.

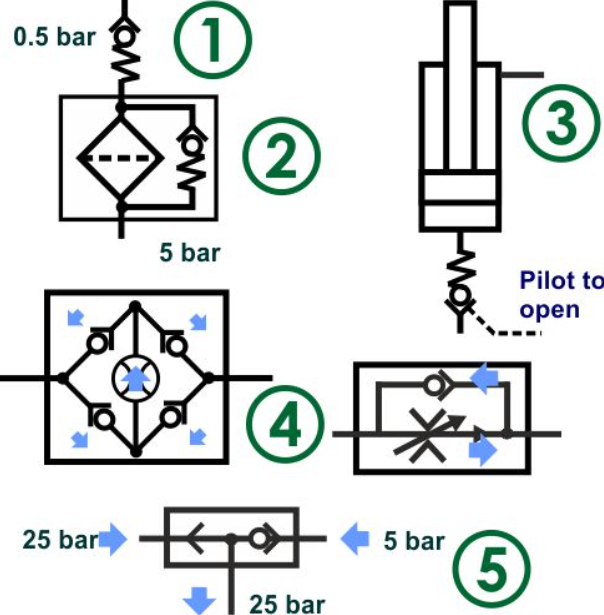

The hydraulic industry has maybe six or seven common check valve designs, but in practice, you’re using three types for 90% of applications.

Standard poppet check valves are workhorses. Spring-loaded poppet seals against a seat when reverse pressure tries to push back. We use Sun’s CP series for almost everything – they’re cartridge style, so they drop into manifold cavities, and you can swap them out in ten minutes if one fails. Cracking pressures range from 0.5 PSI up to 45 PSI depending on the spring. For most circuits, 2-5 PSI cracking pressure is the sweet spot – low enough to minimize pressure drop, high enough to seal reliably.

Ball check valves are cheaper and less precise. A ball sits against a conical seat. They work fine for low-pressure return lines where you just need basic backflow prevention, but the sealing isn’t great. We had a customer try to use ball checks for an accumulator isolation circuit. The leakage was bad enough that the accumulator would lose 200 PSI overnight even with the pump off. Switched to poppet checks, problem solved.

Pilot-operated check valves are the sophisticated option. They hold pressure in one direction like a standard check, but you can open them remotely with a pilot signal. Critical for load-holding applications. The VBSO series from Eaton is bulletproof – we’ve seen those valves run millions of cycles in injection molding machines without failure. They’re expensive compared to standard checks ($250-400 depending on size), but for safety-critical applications, there’s no substitute.

There’s also inline versus cartridge styles. Inline valves thread directly into your porting – quick to install, but you’re limited by the thread size for flow capacity. Cartridge valves require a manifold, which means more design work upfront, but the flexibility is worth it for anything beyond a simple circuit. You can mix and match different valve sizes in the same manifold cavity, change specifications without repiping, and package everything compactly.

Accumulator circuits need check valves to isolate the accumulator from the pump when the pump shuts off. Sounds simple. But accumulator charging creates pressure pulsations as the pump fills it. If your check valve has too stiff a spring (high cracking pressure), it dampens the pulsations but slows down charging. Too soft a spring (low cracking pressure), and the valve chatters during pulsations, which accelerates wear. For a 3000 PSI accumulator, we typically use 3-5 PSI cracking pressure check valves. Hydac makes accumulator-specific check valves with optimized spring rates that handle the pulsations better than generic valves.

Pump protection circuits are another place where check valve selection makes or breaks performance. Common setup: fixed displacement pump feeding multiple actuators through a priority valve or load-sensing system. You need check valves on each branch to prevent flow from one circuit bleeding into another when it’s not supposed to. The mistake we’ve seen a dozen times: someone specs identical check valves for every branch without thinking about the different flow requirements. Your rapid traverse circuit needs a low cracking pressure check (maybe 1 PSI) because flow rates are high and you want minimal pressure drop. Your precision positioning circuit can use a 3-5 PSI check because flow is lower and you want better isolation between circuits. Use high cracking pressure checks everywhere, and your high-flow circuits generate excessive heat. Use low cracking pressure checks everywhere, and you get poor circuit isolation and erratic operation.

Mobile equipment circuits – excavators, loaders, aerial lifts – often use pilot-operated checks for boom and bucket control. The cylinder has to hold position when the operator takes his hand off the controls, even on a slope. Standard check valves will leak enough over time that the boom drifts. Pilot-operated checks with reverse leakage specs under 0.3 cubic inches per minute are mandatory. We work with a lot of utility truck manufacturers, and they exclusively use Parker CPOM or Sun CXBA series valves for any load-holding cylinder. The cost difference versus a standard check is maybe $200 per valve, but the liability risk of a boom drifting and injuring someone is infinitely higher.

Reverse flow leakage is the critical spec for holding applications, and a lot of datasheets don’t even list it clearly. A poppet check valve will leak 1-3 drops per minute at rated pressure if it’s in good condition. Ball checks leak more – maybe 10 drops per minute or worse. For reference, Sun Hydraulics lists their CP series at less than 0.2 cubic inches per minute reverse leakage at 5000 PSI differential. That’s good performance. If a datasheet just says “tight shutoff” or “minimal leakage” without numbers, don’t use that valve for anything where leakage matters.

Reverse leakage gets worse with wear. After a few million cycles, the poppet seat wears, contamination damages the sealing surface, and leakage increases. We’ve measured valves in the field that started at 0.2 in³/min when new and were leaking 2.0 in³/min after five years of service. Still within acceptable range for many applications, but if you’re designing for ten-year service life, factor in that degradation.

Cracking pressure seems straightforward – the pressure required to open the valve – but there’s more to it. Cracking pressure increases as the spring fatigues over time. A valve rated at 3 PSI cracking pressure might be 3.5 PSI after five years. Temperature affects it too: at 180°F, the cracking pressure can drop 20% compared to 70°F because the spring relaxes. This matters in high-temperature applications like die casting machines where oil temperatures regularly hit 160-180°F.

Response time for pilot-operated checks depends on pilot pressure rise time and the internal volume that has to fill before the valve opens. Typical response is 50-200 milliseconds. For high-speed circuits or counterbalance valves where you need fast response, this lag can cause instability. The cylinder might jerk or oscillate as the check valve opens and closes slightly out of phase with the directional control valve. We usually test pilot-operated check valves on the actual circuit before finalizing the design, because the datasheet response time doesn’t always match real-world performance.

Wrong flow direction – you’d think this is obvious, but we’ve been called to troubleshoot systems where someone installed a check valve backward. The arrow on the valve body is hard to see after you’ve painted the manifold. Or the previous technician assumed the arrow pointed toward the cylinder instead of toward the pump. Always verify flow direction with a schematic before you pressurize anything. And put flow direction arrows on the manifold casting if you’re designing custom manifolds, not just on the valves.

Contamination is the number one killer of check valves. A single piece of metal swarf can hold the poppet off the seat, and suddenly your check valve isn’t checking anything. We require 10-micron absolute filtration for any circuit with pilot-operated check valves. Standard poppet checks can tolerate 25-micron filtration, but cleaner is always better. And system flushing during commissioning isn’t optional – we’ve seen new systems contaminated with weld slag, pipe dope, and metal particles from machining operations. All that junk ends up in your check valves.

Port sizing matters more than people realize. Installing a 3/4″ check valve with 1/2″ pipe fittings negates any flow advantage from the larger valve. The porting creates a restriction that increases pressure drop. Always match or exceed the valve’s port size with your piping and fittings. If you’re using a size 16 cartridge check valve (1″ cavity), your manifold porting should be at least 3/4″ diameter, preferably 1″.

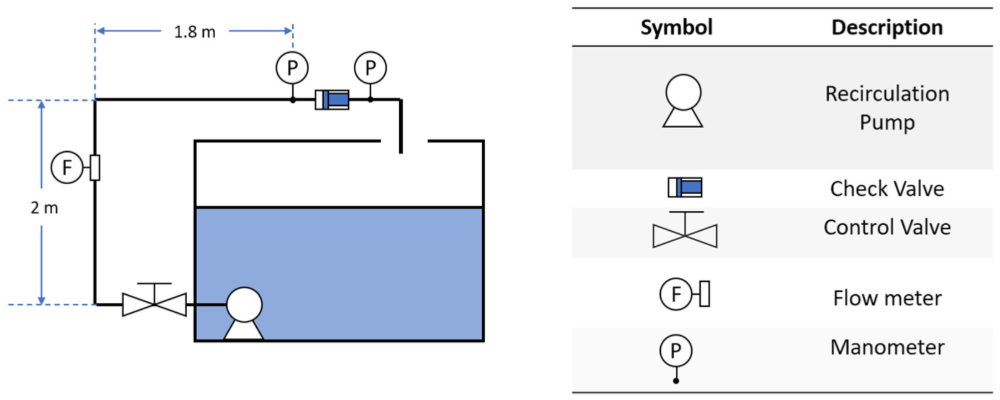

No test ports is a design mistake we see constantly. When you’re troubleshooting a check valve issue, you need pressure gauge ports upstream and downstream of the valve to measure actual cracking pressure and pressure drop. Without test ports, you’re pulling valves out for bench testing or just guessing. We always design manifolds with at least two test ports per critical check valve. Costs maybe $40 extra per manifold but saves hours of troubleshooting time.

We instrumented a plastic injection molding machine last year to measure check valve performance in the clamp circuit during production. The setup: 4-inch bore cylinder with a pilot-operated check valve (Eaton VBSO-16-50) holding tonnage during the injection phase. We logged data for 1000 molding cycles over three shifts.

Holding pressure ranged from 2850-2900 PSI with about 50 PSI variation due to thermal expansion of the oil as it warmed up during the shift. Reverse leakage measured 0.15 cubic inches per minute average, which is within spec for that valve. Opening response time was 85 milliseconds with 1000 PSI pilot pressure. Forward flow pressure drop measured 28 PSI at 15 GPM.

The valve worked perfectly. But here’s the interesting part: this machine originally had a cheaper ball-type check valve to save $200 on the build cost. The ball check leaked about 1.8 cubic inches per minute – twelve times more than the pilot-operated check. That leakage caused the mold halves to shift slightly during the cycle, creating flash and dimensional problems. Scrap rate was running 8-12% on some parts. After we replaced the ball check with the VBSO pilot-operated valve, scrap dropped to under 2%. The valve paid for itself in reduced scrap within two weeks of production.

Cylinder drifts under load – first thing to check is reverse leakage through the check valve. Install a pressure gauge on the holding side and watch it over time. If pressure drops steadily, you’ve got leakage. Could be worn valve seat, contamination holding the poppet off the seat, or you’re using the wrong type of valve (standard check instead of pilot-operated for a holding application). We had a customer try to use standard poppet checks for vertical cylinder holding because they were cheaper. The cylinders drifted 0.030″ per hour. Switched to pilot-operated checks, drift dropped to unmeasurable levels.

Slow or erratic cylinder movement might be caused by check valve cracking pressure that’s too high for the available system pressure. Or if you’re using pilot-operated checks, insufficient pilot pressure to open the valve smoothly. We’ve also seen cavitation from flow restriction when check valves are badly undersized. Measure the pressure drop across the check valve at operating flow – if it’s more than 10% of system pressure, the valve is either undersized or malfunctioning.

System overheating often traces back to check valves. Excessive pressure drop equals wasted energy that converts to heat. Calculate the total pressure drop from all check valves in your circuit. If you’re losing more than 50 PSI combined at rated flow, something’s wrong. Either the valves are undersized, worn, or contaminated. We fixed an overheating problem on a 40 GPM system last year by replacing six undersized check valves. Oil temperature dropped 18°F.

For load-holding applications – vertical cylinders, precision positioning, anything where drift is unacceptable – use pilot-operated check valves. Spec reverse leakage under 0.5 cubic inches per minute. Pilot ratio should be 3:1 to 5:1 depending on your pressure requirements. We standardize on Parker CPOM, Eaton VBCD, or Sun CXBA series because they’re proven reliable and available worldwide for service.

Pump protection and branch isolation circuits work fine with standard poppet check valves. Cracking pressure 1-3 PSI. Size the valve for twice your maximum flow rate to keep pressure drop reasonable. Sun CP series or Parker C2S are good options.

Accumulator charging needs poppet checks with optimized springs for handling pressure pulsations. Cracking pressure 3-5 PSI. Flow coefficient should be over 4.0 for systems above 10 GPM. Hydac and Tobul make accumulator-specific check valves that work better than generic valves.

Low-pressure return lines don’t need anything fancy. Ball check valves are cost-effective and adequate. Cracking pressure 1-2 PSI. Just make sure they’re sized for your flow rate.

Most check valve datasheets list ideal performance numbers measured in perfect laboratory conditions. Reality is different. Springs fatigue over time – cracking pressure typically increases 10-15% over five years. Reverse leakage doubles or triples after 5-10 million cycles if there’s any contamination in the system. Temperature swings affect performance more than the datasheets suggest. And cheap valves from no-name suppliers might have casting porosity that causes unpredictable leakage.

This is why we stick with known manufacturers. Sun, Parker, Eaton, Bosch Rexroth – their quality control is consistent. You know what you’re getting. Random valves from overseas suppliers with no traceable specifications? We’ve been burned enough times to avoid them entirely, even when the price is tempting.

Customer needed check valves for a dual-cylinder press system. Requirements: two 3-inch bore cylinders operating in parallel, 3000 PSI maximum system pressure, 20 GPM pump (10 GPM per cylinder), cylinders must hold position during a welding operation.

We specified Parker CPOM-16-50 pilot-operated check valves for position holding, one valve on each cylinder rod port. Pilot ratio is 4:1, so they need 750 PSI pilot pressure to open when holding 3000 PSI. Reverse leakage spec is under 0.3 cubic inches per minute. Cost about $285 each.

For pump branch protection, we used Sun CP12-2 poppet check valves on the supply lines. Cracking pressure is 2 PSI, flow coefficient is 3.8, which gives about 6 PSI pressure drop at 10 GPM per valve. Cost around $95 each.

Total check valve investment was $760 for a system that should last ten years with proper maintenance and filtration. The customer tried to value-engineer it with cheaper valves initially, but after we explained the performance and reliability difference, they went with our recommendation. System’s been running flawlessly for two years now.

For complex circuits or high-reliability requirements, talk to the application engineers at Parker, Eaton, or Sun Hydraulics before you finalize your design. They’ll review your circuit and recommend valve configurations based on actual field experience with similar applications. It’s a free service that can save you from expensive mistakes. We use it regularly, especially when we’re designing something outside our normal application range.

And when you’re troubleshooting hydraulic problems that don’t make sense, check your check valves. They’re small, cheap, and easy to overlook, which is exactly why they cause so many problems. Pull them out, bench test them for leakage and cracking pressure, and you’ll often find the issue right there.