Menu

Directional control hydraulic valves increase maintenance time primarily due to their complex internal architecture, tight tolerances, and multiple precision components that require systematic inspection and servicing. A typical directional control valve contains spools with clearances as small as 5-30 micrometers, multiple seals, and intricate flow paths that demand specialized diagnostic procedures and skilled technicians to maintain properly.

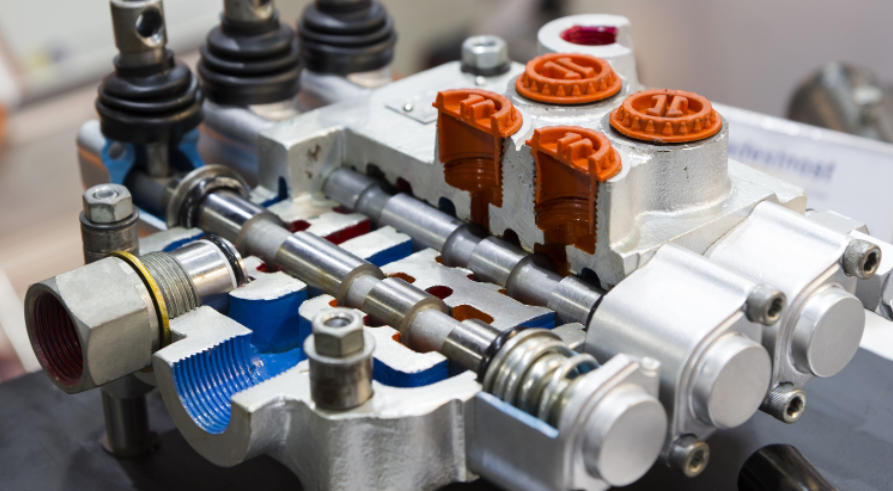

The fundamental design of directional control hydraulic valves creates maintenance challenges that simpler components don’t face. These valves house cylindrical spools within precision-machined bores, where the spool’s lands and grooves control fluid flow by opening and closing specific pathways. This precision engineering, while essential for accurate hydraulic control, makes maintenance more time-consuming.

Consider a standard 4/3-way directional control valve – the most common configuration in hydraulic systems. This valve contains four ports and three spool positions, allowing fluid to route in multiple directions depending on the spool’s location. Each position must be tested, each port checked for blockages, and each seal examined for wear. A study from the hydraulic maintenance sector indicates that contamination causes 60-70% of all hydraulic component failures in manufacturing environments, rising to 85-90% in earthmoving equipment.

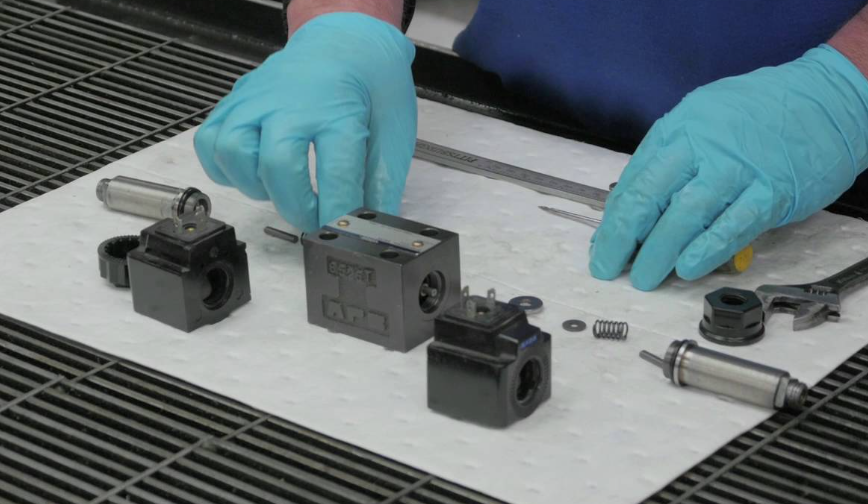

The radial clearance between spool and bore typically measures less than 0.02 mm. This tight tolerance prevents leakage but creates vulnerability. Even microscopic particles can lodge between the spool and housing, causing the valve to stick or malfunction. When this occurs, technicians must disassemble the valve, clean all components in a controlled environment to prevent contamination, inspect the spool for scoring or wear, and reassemble with new seals – a process that can take several hours for a single valve.

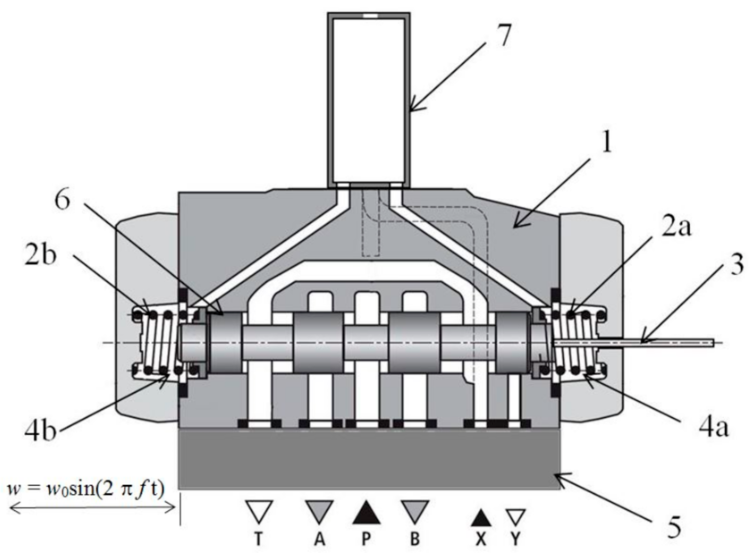

Directional control hydraulic valves employ four primary actuation methods, each requiring different maintenance approaches. Manually-operated valves need inspection of mechanical linkages, handles, and detents. Solenoid-operated valves require electrical testing with multimeters to verify coil resistance and voltage, typically around 12V or 24V DC. Pilot-operated valves demand pressure testing of pilot circuits and inspection of pilot pistons. Mechanically-operated valves need cam and roller assembly examination.

This variety means maintenance personnel must possess broader diagnostic skills compared to simpler components. A hydraulic technician working on a manifold with eight directional control valves might encounter three different actuation types, each presenting distinct failure modes. Solenoid burnout requires different diagnostic steps than pilot pressure failure. Internal spool sticking demands different solutions than external seal leakage.

Testing procedures add time. Technicians must use manual overrides to separate electrical from mechanical problems, conduct pressure tests at inlet and outlet ports simultaneously, and verify operation at different pressure settings since worn valves may function at high pressure but fail at lower pressures. Each test requires system pressure adjustment, observation periods, and documentation.

External and internal seals in directional control valves degrade over time due to thermal cycling, chemical exposure, and mechanical wear. Unlike simple shut-off valves with one or two seals, a directional control valve may contain 5-10 seals depending on configuration – spool seals, port seals, end cap O-rings, and solenoid cartridge seals.

Accessing these seals requires systematic disassembly. Technicians must remove the handle bracket, extract end caps, carefully slide out the spool without scoring the bore, and catalog each seal’s position. Cross Mfg., a valve manufacturer, notes in their service manual that spool seals can be replaced by removing the handle bracket and end cap, but the process must be executed in a clean environment to prevent contamination during reassembly.

The replacement process extends beyond simple part swapping. Each new seal must be lubricated with compatible hydraulic fluid, properly seated in its groove, and the housing cleaned before reassembly. Torque specifications must be followed precisely – overtightening can damage the valve body, while undertightening causes leaks. LOCTITE application on cap screws adds another step. For a valve bank with multiple sections, this process multiplies across each spool.

Contamination stands as the primary maintenance driver for directional control valves. When hard particles enter the system, they lodge between the spool and bore, increasing the force required to move the spool beyond what the operator can provide. This contamination doesn’t announce itself clearly – operators first notice sluggish response or hesitant movement before complete failure occurs.

Addressing contamination requires more than just cleaning the visible valve exterior. The entire valve body must be flushed, internal passages cleared with compressed air or approved solvents, and the bore inspected for scoring. If particles have scored the spool or bore surface, the valve typically requires replacement rather than repair, as these precision surfaces cannot be easily refinished.

Parker Hannifin’s hydraulic maintenance guidelines emphasize that proper contamination control through fluid analysis and filtration prevents most valve failures. However, implementing this prevention requires regular fluid sampling from main flowlines, laboratory analysis to determine ISO particulate levels, and filter changes based on actual contamination levels rather than fixed schedules. Each of these activities consumes maintenance time.

Three main failure modes affect directional control valves: sticking/binding, internal leakage, and external leakage. Each requires different diagnostic approaches and time investments.

Sticking or binding can originate from multiple sources. Contamination between spool and bore is most common, but thermal expansion from viscous friction heat, mechanical damage, or incorrect assembly also cause binding. Diagnosis requires determining whether the problem lies in the hydraulic section or the operator. Technicians use manual overrides to test mechanical function separately from electrical signals. If the valve shifts with manual override but not with normal signals, the operator (solenoid, pilot circuit, or linkage) needs attention. If manual override fails, the problem exists in the hydraulic section.

Internal leakage presents particularly challenging diagnosis. All directional control valves allow some internal leakage – they’re not designed to close completely. However, excessive leakage reduces system efficiency without obvious external signs. Technicians observe slower cycle times, reduced actuator speeds, and drift when actuators should remain stationary. Confirming internal leakage requires pressure and flow meter testing at multiple points while the valve operates. For pilot-operated valves, checking internal or external drain ports for blockage adds another diagnostic step.

External leakage proves easier to identify visually but still requires systematic troubleshooting. Leaks can originate from seal failure, spool wear, pushpin wear, or solenoid core tube failure. According to data from valve repair facilities, seals, push pins, and solenoids can be replaced, but if the seal area of an exposed manually-operated spool becomes worn or damaged, the entire valve needs replacement.

Directional control valve center positions – the state when the spool sits in neutral – come in multiple configurations: open center, closed center, tandem center, and float center. Each configuration serves different hydraulic system architectures and creates distinct maintenance considerations.

Open center valves, typically paired with fixed-displacement gear pumps, allow fluid to flow freely to tank in neutral position. This continuous flow generates heat, which accelerates seal degradation and oil oxidation. Maintenance intervals must account for this thermal stress. Closed center valves, used with pressure-compensated pumps, block all ports in neutral, creating different wear patterns. The valve must seal against system pressure continuously, testing seals differently than open center designs.

Converting between center types adds complexity. Many valves allow field conversion by installing or removing plugs in specific ports. However, this conversion requires understanding the system’s pump type, pressure requirements, and flow characteristics. Incorrect conversion leads to immediate operational problems – using an open center valve in a closed center system or vice versa causes pressure buildup, overheating, or failure to hold loads.

Industry guidelines recommend preventive maintenance schedules that vary by application severity. For critical directional control valves in manufacturing, quarterly or semi-annual inspection is standard. Construction equipment operating in contaminated environments requires monthly comprehensive checks. Each maintenance cycle includes:

Daily tasks for operators: Visual inspection for leaks, monitoring fluid temperature, checking pressure gauges. While quick, these checks interrupt production flow.

Weekly to monthly tasks: Checking fluid levels, inspecting hoses and connections, verifying actuator response, listening for unusual noises. These require 30-60 minutes per system.

Quarterly to semi-annual tasks: Fluid analysis, filter replacement, seal inspection, spool movement verification, electrical testing of solenoids, pilot pressure testing. A single valve bank can consume 2-4 hours.

Annual overhauls: Complete disassembly, internal cleaning, seal kit installation, bore and spool inspection, reassembly with proper torque, system pressure testing, and function verification. For complex manifolds with multiple directional control valves, annual overhauls can span multiple days.

Valmet’s maintenance scheduling guidelines note that piston pumps typically require service every 10,000 hours (approximately 14 months), but proportional valves connected to those pumps need service coordination through the component manufacturer, extending the service window.

Maintaining directional control valves effectively requires knowledge that extends beyond basic hydraulic principles. Technicians must understand spool valve configurations, read hydraulic schematics showing port designations (P for pressure, T for tank, A and B for work ports), interpret ISO 1219 valve symbols, use diagnostic equipment like multimeters and pressure gauges, and follow manufacturer-specific procedures.

This specialized knowledge means not all maintenance personnel can work on directional control valves efficiently. Organizations must invest in training or rely on fewer qualified technicians, creating bottlenecks during scheduled maintenance windows or emergency repairs. GES Repair, a hydraulic service provider, emphasizes that “how long it takes to break down the valve will depend on the complexity of the valve, but we take as long as is required to systematically separate every piece that could potentially have a problem.”

The learning curve for different valve brands and models adds time. While basic principles remain consistent, manufacturer-specific features, seal kit designs, and assembly procedures vary. A technician familiar with Parker valves may need additional time working with Bosch Rexroth or Moog valves, even for similar maintenance tasks.

The time required for directional control valve maintenance directly impacts operational costs through downtime. Facilities typically schedule outages, turnarounds, or shutdowns lasting from days to weeks for preventive maintenance. During these windows, directional control valves must be removed, evaluated, repaired or replaced, and reinstalled.

A hypothetical scenario illustrates the time investment: A facility with 40 directional control valves needing repair faces a complex decision. If repairing each valve costs $2,500, the total quote reaches $100,000 with a three-week delivery in partial shipments. This three-week period represents lost production time beyond the physical maintenance work. The alternative – replacing all valves at $200,000 – eliminates discovery work time but requires coordinating workforce for removal, installation, welding for permanent installations, proper equipment staging, decontamination of old valves, and sequential work planning.

The “discovery work” phase particularly extends maintenance time. Once technicians inspect valves, they typically find additional repairs needed beyond the initial assessment, potentially adding 40% to the quoted time and cost. Each discovered issue requires new parts procurement, work order modification, and schedule adjustment.

Recent advancements in diagnostic technology help reduce some maintenance time, though the fundamental complexity remains. Microprocessor-based tools like ValScope-PRO allow in-situ testing without system shutdown. Technicians can detect deadband, stiction, and other problems while equipment runs, then plan specific repairs during scheduled downtime rather than conducting exploratory disassembly.

Predictive maintenance using these tools enables technicians to establish performance baselines, track degradation over time, and schedule interventions before failures occur. This approach can extend maintenance intervals from annual to every 2-4 years for valves performing within acceptable parameters. However, the initial investment in diagnostic equipment and training creates its own time requirement.

Despite these improvements, a directional control valve in a severe-service application still demands more maintenance hours annually than simpler hydraulic components. The precision engineering that makes these valves capable of complex flow control simultaneously makes them more time-intensive to maintain.

The tight tolerances between spool and bore (typically 0.02 mm) make directional control valves extremely sensitive to contamination. Even microscopic particles that pass through other components can lodge in these narrow clearances, causing the valve to stick. Additionally, the multiple seals and moving parts create more potential failure points than static components like pipes or fittings.

Service time varies significantly by valve complexity and service type. A basic seal replacement on a simple 3-way valve might take 45-90 minutes. A complete overhaul of a multi-section manifold with eight 4-way valves can require 8-16 hours of technician time, plus additional hours for system flushing and pressure testing.

Internal leakage symptoms include slower cycle times, reduced actuator speeds, and drift when actuators should remain stationary. Technicians can confirm excessive internal leakage using pressure differential testing and flow rate measurements at various ports while the valve operates, but determining the exact internal damage location typically requires disassembly for visual inspection.

Spool sticking results primarily from contamination between the spool and bore, thermal expansion from operating heat, or corrosion. Prevention focuses on maintaining clean hydraulic fluid through proper filtration (typically 10-micron or finer), using fluid analysis to monitor contamination levels, keeping operating temperatures within design limits, and following preventive maintenance schedules that include regular cleaning and lubrication.

The maintenance time required for directional control hydraulic valves reflects a trade-off inherent in hydraulic system design. The same precision engineering that enables sophisticated motion control – the fine clearances, complex spool configurations, and multiple sealing surfaces – creates maintenance demands that simpler components avoid. While preventive maintenance programs and advanced diagnostic tools help optimize maintenance efficiency, the fundamental reality remains: directional control valves require more systematic attention, specialized skills, and time investment than most other hydraulic components. Organizations using hydraulic systems must account for this maintenance reality in their operational planning and budget allocation.