Menu

Hydraulic directional control valves must meet pressure ratings that match system demands, comply with international standards like ISO 4413:2012, and incorporate fail-safe mechanisms. These requirements ensure valves prevent overpressure scenarios, contain fluid leaks, and maintain predictable failure modes during electrical or mechanical disruptions.

Hydraulic directional control valves operate within defined pressure boundaries that determine their safe operational envelope. The maximum working pressure varies by valve size and design—ISO 4401-03 (NFPA D03) valves typically handle up to 350 bar (5,000 psi), while larger D07 and D08 configurations manage pressure ratings up to 350 bar on primary ports with reduced ratings of 250 bar (3,600 psi) on tank ports.

Continental Hydraulics’ TÜV-certified valves demonstrate compliance with multiple European safety frameworks including ISO 4413:2012 for hydraulic fluid power systems, UNI EN 12622:2014 for hydraulic presses, and UNI EN 693:2001 for machine tool safety. These certifications verify that valves maintain structural integrity under maximum rated pressure while preventing catastrophic failures.

Flow capacity presents another critical safety parameter. Undersized valves create bottlenecks that generate excessive heat and pressure spikes, while oversized configurations may produce unexpected pressure drops. D05 valves accommodate nominal flows to 40 GPM, D07 handles 80 GPM, and D10 configurations manage up to 290 GPM. Exceeding these specifications forces fluid through restricted passages at velocities that erode internal components and compromise sealing surfaces.

Temperature specifications define the operational safety window for hydraulic fluids. Most directional valves function reliably between -20°C and 80°C, with specialized low-temperature variants extending operation to -40°C for mining and outdoor applications. Fluid viscosity changes outside this range affect spool response times and internal leakage rates, potentially causing valves to stick or fail to shift when commanded.

The regulatory framework for hydraulic directional control valves spans multiple jurisdictions and application contexts. ISO 4401 establishes mounting interface dimensions and port patterns, ensuring physical interchangeability between manufacturers while standardizing pressure port locations that affect installation safety. This standardization prevents connection errors that could reverse flow direction or route high pressure to components rated for lower pressures.

Explosive atmosphere applications require ATEX, IECEx, and INMETRO certifications for valves deployed in mining operations or chemical processing facilities. These certifications verify that electrical actuation systems and mechanical components won’t generate sparks or surface temperatures capable of igniting flammable vapors. Specialized coatings like zinc-nickel finishing provide 600-hour salt spray resistance for offshore and marine installations where corrosion could compromise valve integrity.

Machine safety directives, particularly 2006/42/EC, mandate that safety-critical applications use valves with position monitoring capabilities. Spool Position Monitored Valves provide electrical feedback confirming valve state, allowing control systems to verify that commanded positions match actual positions. This verification becomes essential in applications where unexpected actuator movement could injure operators or damage equipment.

For industrial automation and press applications, valves must achieve Safety Integrity Level (SIL) ratings defined by IEC 61508. Atos Hydraulics manufactures directional valves certified to SIL 2 and SIL 3, with ISO 13849 Performance Level (PL) ratings reaching Category 4, PL e. These ratings quantify the probability that a valve will perform its safety function when demanded, with higher ratings indicating more reliable safety performance.

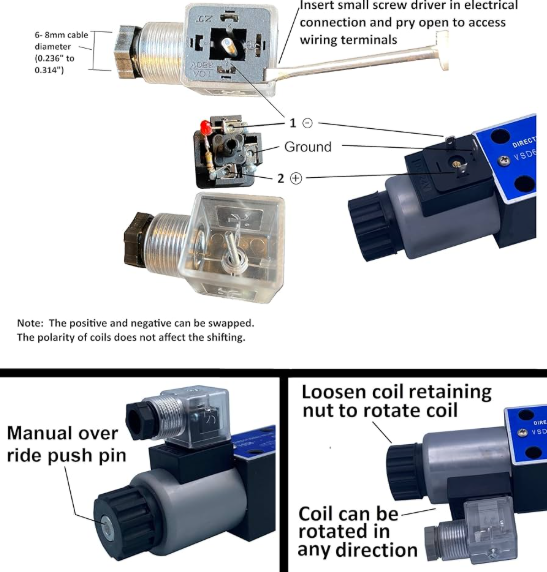

Solenoid-operated directional control valves introduce electrical hazards that require specific safety measures. Voltage compatibility represents the most fundamental requirement—applying AC voltage to DC-rated solenoids or exceeding rated voltage causes coil failure that may result in stuck valves or thermal damage. Standard solenoid ratings include 24V DC, 110V AC, and 230V AC, with tolerance ranges typically ±10%.

Coil protection against moisture ingress follows IP (Ingress Protection) ratings. IP65-rated solenoids resist water jets and dust ingress suitable for indoor industrial environments, while IP67 ratings provide temporary immersion protection for mobile equipment. Inadequate IP ratings allow moisture to compromise coil insulation, creating short circuits that disable valve operation or pose electric shock hazards.

Inrush current during solenoid energization exceeds steady-state current by factors of 3 to 8 times. Circuit protection must accommodate this transient without nuisance tripping while still protecting against sustained overcurrent conditions. Delayed-action fuses or circuit breakers with appropriate time-current characteristics prevent false trips during normal valve actuation.

Pilot-operated valves using smaller solenoids to control pilot pressure reduce electrical power consumption and heat generation compared to direct-operated designs. When pilot pressure fails while the main spool remains pressurized, trapped pressure can hold the valve in an intermediate position. Safety requires external pilot drain connections that prevent pilot pressure accumulation, with drain line sizing adequate to handle maximum pilot flow without creating back pressure that interferes with spool shifting.

Spool design incorporates pressure balancing to prevent hydraulic clamping—a condition where radial forces bind the spool within the bore. Pressure equalization grooves machined into the spool distribute forces evenly, but contamination filling these grooves eliminates their effectiveness. Maintaining fluid cleanliness to NAS 1638 Grade 12 or better (25-micron filtration) prevents particles from jamming between spool and bore surfaces.

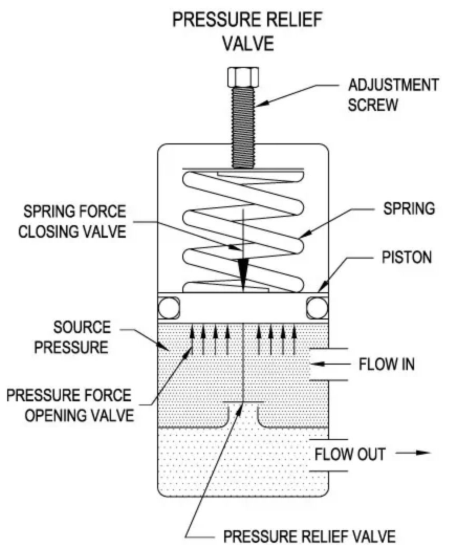

Spring failures in directional valves create unpredictable failure modes. Relief valve springs experiencing fatigue allow system pressure to exceed safe limits, while directional valve spring degradation prevents proper centering or position holding. Spring-centered valves may drift under load if spring force becomes insufficient to overcome flow forces acting on the spool.

Internal leakage through worn spool-to-bore clearances generates heat while reducing actuator speed. As clearances increase through erosive wear, leakage rates accelerate, creating a self-reinforcing failure mode where increased leakage produces more heat that further accelerates wear. Sliding spool designs showing slower cycle times or drifting actuators indicate internal wear requiring valve replacement.

Manual override mechanisms provide emergency operation capability when electrical or pilot pressure fails. However, manual overrides on pilot-operated valves cannot shift the main spool if hydraulic binding or contamination prevents movement. Testing manual overrides during maintenance verifies that mechanical operation remains possible independent of electrical and pilot systems.

Directional control valves in closed-center configurations trap actuators under load, requiring integrated relief protection. Adjustable relief valves preset between 500-2,500 psi at the factory protect against overpressure from thermal expansion, external forces on trapped actuators, or control system malfunctions. These reliefs must be set at least 200 psi below system relief pressure to ensure they function before system-level protection engages.

Pressure release detents allow springs to overcome detent resistance when pressure exceeds preset levels, automatically centering the valve spool. This feature prevents pressure buildup in blocked ports while maintaining position holding under normal loads. Factory preset at 1,000 psi, these detents adjust using the same procedure as relief valves but must always remain below relief settings to function properly.

The American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME) Boiler and Pressure Vessel Code establishes requirements for pressure vessels in hydraulic systems. OSHA 1910.169 mandates that air receivers and hydraulic accumulators include properly sized relief valves that prevent pressure from exceeding maximum allowable working pressure by more than 10%. These requirements apply to the complete hydraulic system, not just individual valves.

Lockout/Tagout (LOTO) procedures prevent unexpected valve actuation during maintenance. Isolating electrical power to solenoids alone proves insufficient because residual pressure in lines or trapped actuators may cause movement when hydraulic connections open. Comprehensive LOTO requires electrical isolation, hydraulic pressure release through manual overrides, and physical blocking of actuators before personnel access hazard zones.

Personal protective equipment for hydraulic maintenance includes eye protection against high-pressure fluid injection injuries—hydraulic fluid escaping through pinhole leaks can inject into skin at pressures sufficient to cause tissue damage requiring surgical intervention. Gloves resistant to petroleum-based or synthetic hydraulic fluids prevent skin contact that may cause dermatitis from prolonged exposure.

Startup procedures for systems with directional valves emphasize gradual pressure buildup. Rapidly pressurizing dormant systems forces cold, viscous fluid through narrow clearances, potentially causing seals to extrude or generating pressure transients that damage components. Pre-warming hydraulic reservoirs and using low-pressure operation during initial cycles reduces thermal shock and verifies valve function before full-load operation.

Center spool configurations affect safety during system shutdown. Open-center valves allow free cylinder movement, potentially causing load drops if gravity or external forces act on connected actuators. Closed-center or tandem-center configurations prevent actuator drift but trap pressure that requires deliberate release before maintenance. Selecting appropriate center conditions requires analyzing load-holding requirements against operational safety needs.

Hydraulic fluid contamination represents the primary cause of directional valve failure. Hard particles scoring spool or bore surfaces increase internal leakage while potentially causing catastrophic jamming. Maintaining filtration to 25 microns absolute in supply lines and 10 microns on pilot oil supplies prevents particles capable of jamming typical spool-to-bore clearances of 5-15 microns.

Water contamination in hydraulic fluids corrodes steel valve bodies and spools, creating rust particles that accelerate wear while reducing lubrication effectiveness. Water content exceeding 0.1% by volume in petroleum-based fluids promotes microbial growth that forms sludge deposits on valve internals. These deposits increase friction, causing spools to stick and preventing proper shifting response.

Fluid compatibility with valve seals determines long-term reliability. Petroleum-based fluids (ISO VG 32 or VG 46 viscosity grades) suit standard nitrile (Buna-N) seals, while phosphate ester fire-resistant fluids require fluoroelastomer seals. Using incompatible fluids causes seal swelling or shrinkage that either prevents spool movement or creates leak paths. Valve manufacturers identify required seal materials for alternative fluids through model number prefixes like “F-” for fluoroelastomer construction.

Temperature affects fluid viscosity directly—cold fluid becomes sluggish, delaying valve response, while overheated fluid loses viscosity, increasing internal leakage. Maintaining reservoir temperatures between 40°C-60°C balances these concerns. Excessive heat also accelerates fluid oxidation, producing varnish deposits that coat valve internals and impede spool movement.

Mounting surface flatness directly impacts valve body integrity and spool alignment. Uneven mounting surfaces distort the valve body when mounting bolts tighten, potentially binding the spool or causing internal leakage paths. Surface flatness specifications typically require deviations under 0.05mm across mounting interfaces, with tightening torques applied in cross-pattern sequences to distribute clamping forces evenly.

Port size and connection type must match system requirements. Threading adapters into ports reduces flow area, creating restrictions that generate heat and pressure drop. Using ports sized for actual flow rates—typically requiring fluid velocities under 20 ft/sec in pressure lines and under 10 ft/sec in return lines—prevents cavitation and excessive turbulence that damages valve internals.

Subplate mounting requires O-ring groove condition verification. Scratched or corroded groove surfaces allow fluid to bypass O-rings, causing external leaks or cross-port contamination that degrades control precision. O-ring materials must suit fluid type and temperature, with durometer hardness (typically 70-90 Shore A) selected to provide adequate sealing without excessive compression set.

Pipe and hose routing affects valve performance through pressure transients. Rigid piping without vibration isolation transmits shock loads directly to valve bodies, potentially cracking housings or loosening internal components. Pressure spikes from rapid directional changes in upstream components can exceed valve ratings momentarily—installing inline accumulators near valves dampens these transients before they reach valve inlets.

Periodic inspection intervals depend on operating conditions and duty cycles. Mobile equipment operating in contaminated environments requires more frequent inspections than clean industrial applications. Monthly visual inspections should identify external leaks, damaged fittings, or corroded surfaces, while quarterly functional tests verify proper valve shifting and pressure relief operation.

Seal replacement intervals typically range from 2,000 to 10,000 operating hours depending on fluid cleanliness and temperature. Preventive seal replacement before complete failure prevents secondary damage from leaked fluid contaminating surroundings or allowing dirt ingress into valve internals. Seal kits include all elastomeric components plus relevant O-rings for relief cartridges and pilot chambers.

Spool-and-sleeve wear assessment requires measuring internal leakage across valve ports. Port-to-port leakage tests at maximum rated pressure quantify internal clearance degradation. Excessive leakage indicates replacement necessity rather than repair, as spool-to-bore clearances cannot be restored without precision machining that typically exceeds valve replacement cost.

Valve testing after maintenance must verify correct operation under actual system conditions. Bench testing at low pressures may not reveal problems that only manifest under full pressure and flow. Testing protocols should include pressure checks at all ports, verification of relief valve settings, and functional confirmation of all spool positions under load conditions representative of actual service.

Valve sticking represents the most frequent failure mode, caused by contamination, corrosion, or mechanical damage. A stuck valve preventing cylinder retraction under gravity load creates fall hazards in material handling applications, while stuck valves in press applications may trap operators if emergency stop commands cannot actuate release. Redundant control paths or mechanical backup release mechanisms mitigate stuck valve risks in safety-critical applications.

Solenoid coil burnout typically results from excessive voltage, duty cycle violations, or insufficient cooling. Burned coils prevent valve actuation, causing processes to halt in safe states if system design assumes “fail-safe” positions. However, pilot-operated valves with burned pilot solenoids may remain in their last position indefinitely, requiring manual intervention to shift. Thermal switches or current monitoring systems detect coil overheating before complete failure.

Internal leakage allows pressurized fluid to bypass intended flow paths, reducing actuator force and speed while generating heat. In safety-critical applications, internal leakage may prevent sufficient force generation to operate brakes or clamps, allowing loads to drift or drop. Regular leak testing and performance monitoring detect degradation before leakage becomes safety-compromising.

External leakage creates slip hazards from fluid spills and environmental contamination from petroleum products. High-pressure jets from pinhole leaks pose injection injury risks—fluid penetrating skin under pressure requires immediate medical attention to prevent tissue necrosis. Leak detection systems and routine inspections identify developing leaks before they progress to catastrophic failures.

The valve’s pressure rating must exceed maximum system pressure by at least 25% to provide safety margin. ISO 4401-03 valves handle 350 bar on main ports, while tank ports typically rate to 250 bar. Consider pressure transients from shock loads or water hammer when specifying ratings.

Check manufacturer documentation for ISO 4413, NFPA, or CE compliance markings. Safety-critical applications require SIL or PL ratings verified by independent testing laboratories. TÜV or UL certifications indicate third-party safety validation.

Contaminated fluid causes 70-80% of valve failures by scoring seals and jamming spools. Other causes include excessive temperature, voltage errors on solenoids, spring fatigue, and improper fluid viscosity. Maintaining clean, temperature-controlled fluid prevents most failures.

Most valves include manual overrides allowing mechanical actuation when electrical or pilot systems fail. However, if contamination or hydraulic binding prevents spool movement, manual overrides cannot shift pilot-operated valves. Testing overrides during maintenance verifies emergency operation capability.

Key Sources