Menu

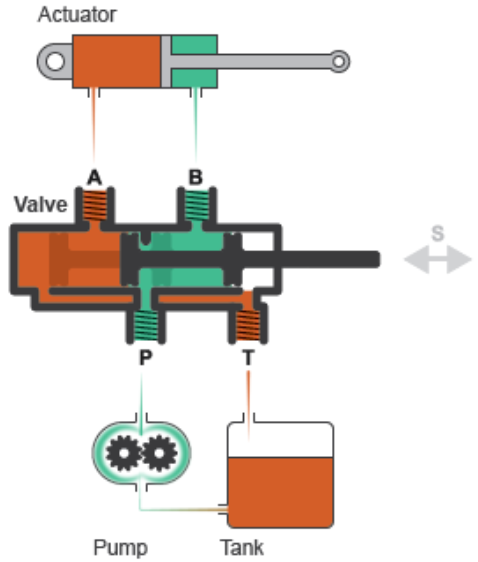

Directional control valves regulate fluid pathways in hydraulic and pneumatic systems by opening, closing, or redirecting flow channels. These valves determine where pressurized fluid travels within a circuit, enabling machinery to extend cylinders, rotate motors, or halt movement entirely.

The valves accomplish flow management through internal elements—typically spools, poppets, or rotary mechanisms—that shift position when activated. A spool valve, for instance, contains a cylindrical component with lands and grooves that align with port openings as it slides within a precision-machined housing. When an operator actuates the valve through manual, electrical, or hydraulic means, the spool repositions to connect the pump port to specific work ports while simultaneously routing return fluid to the reservoir.

Flow direction in hydraulic circuits depends on which ports the valve connects at any given moment. Consider a common 4-port, 3-position valve controlling a double-acting cylinder. In the neutral position, the valve may block all ports, maintaining the cylinder’s position under load. Shifting the valve to the left routes pressurized fluid from the pump to the cylinder’s cap end, causing the piston rod to extend. As extension occurs, fluid displaced from the rod end flows through the valve to the reservoir. Shifting right reverses this process, with pump pressure moving to the rod end to retract the piston.

The valve’s port configuration determines its functional capabilities. A 2-way valve simply permits or blocks flow, functioning similarly to an on-off switch. A 3-way valve adds complexity by including an exhaust port, allowing single-acting cylinders to extend under pressure and retract through spring force or gravity. The 4-way configuration dominates industrial hydraulics because it provides independent control over both sides of double-acting actuators.

Center position characteristics significantly affect flow management behavior. An open center valve allows pump flow to return directly to the reservoir when in neutral, preventing pressure buildup and reducing heat generation. This configuration suits fixed-displacement pump systems commonly found in agricultural equipment. Closed center valves block all ports in neutral, maintaining system pressure—a design preferred in applications requiring rapid response or when multiple actuators operate from a single pump. Tandem center configurations block work ports while connecting pump to tank, offering a compromise that protects against actuator drift while relieving pump pressure.

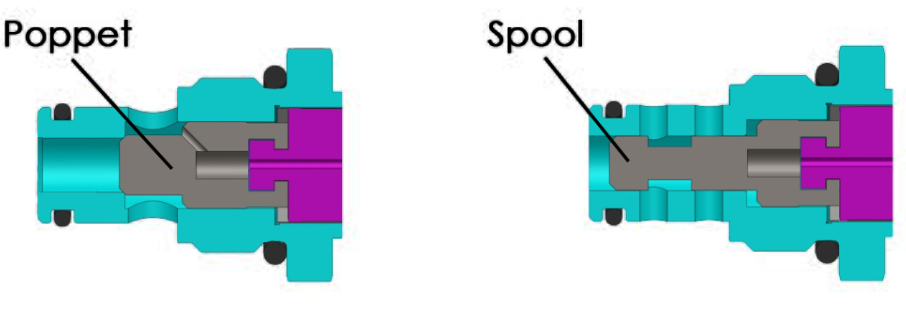

Spool-type valves dominate industrial applications due to their ability to shift between multiple positions and handle complex flow paths. The spool’s cylindrical shape with precisely machined lands creates a sliding seal against the valve body. As the spool moves, lands block certain ports while grooves between lands open others, establishing the desired flow path. Tolerances between spool and bore typically range from 2 to 5 microns, tight enough to minimize leakage yet loose enough to prevent binding under normal conditions.

Poppet valves use a disc or cone-shaped element that seats against an orifice to control flow. When unseated, flow passes with minimal restriction. The sealing action differs fundamentally from spool valves—poppets typically seal with elastomeric or metal-to-metal contact, providing near-zero leakage when closed. This design excels in contaminated environments where particles might jam a spool valve. Poppet valves respond faster than spools because the poppet only needs to lift off its seat rather than travel the full stroke length of a spool. Industrial data shows poppet valves achieving response times of 10-30 milliseconds compared to 30-80 milliseconds for equivalent spool valves.

The trade-off appears in flow capacity and control precision. A spool valve can meter flow proportionally as it moves through its stroke, offering variable flow control. Poppets operate more as binary devices—either open or closed—though pilot-operated poppet designs can achieve some flow modulation. Maximum flow rates favor spools for given valve sizes because the entire circumference of the spool can expose flow passages simultaneously, whereas poppets create more turbulent flow patterns around the poppet head.

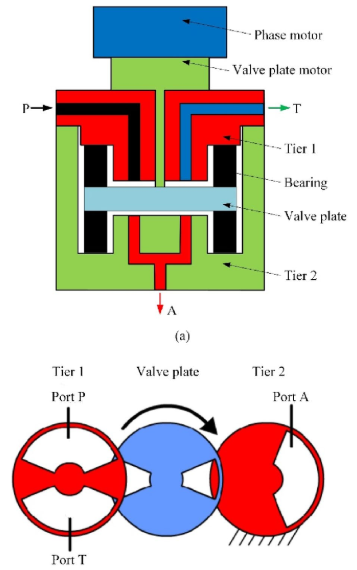

Rotary valves employ a cylindrical or spherical element that rotates to align internal passages with port openings. These valves handle high temperatures and pressures well due to their robust sealing geometry. The rotary motion distributes wear more evenly than the reciprocating action of spools, potentially extending service life in high-cycle applications. However, rotary valves typically offer fewer position options than spool designs and see more limited use in mobile hydraulics.

Construction machinery represents one of the most demanding environments for directional control valves. An excavator’s hydraulic system might incorporate 15-20 directional valves to control boom, stick, bucket, swing, and travel functions. Each valve must respond precisely to operator commands while handling flow rates from 20 to 150 liters per minute at pressures reaching 350 bar. The valves often feature load-sensing capability, where pilot pressure proportional to operator input gradually opens the valve, providing smooth actuator acceleration and preventing hydraulic shock.

Manufacturing operations deploy directional valves in hydraulic presses, injection molding machines, and automated assembly systems. A 400-ton hydraulic press might use a large directional valve to control the main cylinder’s rapid approach, pressing, and return strokes. The valve shifts to route high flow at low pressure during rapid approach, then switches to high pressure at reduced flow during the pressing operation. Precise flow control prevents part damage and ensures consistent product quality. Modern presses incorporate proportional directional valves that adjust flow continuously based on electrical input signals, enabling programmable pressing profiles.

Agricultural equipment relies heavily on directional valves for implements and steering. A modern tractor might have 6-8 auxiliary valve sections for controlling front loaders, backhoes, or various field implements. These valves typically use open center designs to accommodate the tractor’s gear pump, which provides constant flow regardless of demand. When an implement requires flow, shifting the valve directs fluid to the implement while blocking the open center path. The valve automatically returns to open center when released, allowing pump flow to continue to the next valve section in the stack or return to the reservoir.

Material handling applications including forklifts and pallet jacks use compact directional valves to control lifting, tilting, and steering functions. Space constraints in mobile equipment favor integrated valve manifolds where multiple valve sections bolt together in a single assembly. A typical forklift manifold might combine three 3-position, 4-way valves for lift, tilt, and sideshift functions. The valves operate at flow rates of 15-40 liters per minute at pressures around 210 bar, with manual lever operation providing intuitive control for the operator.

Flow rate requirements establish the foundation for valve sizing. Undersized valves create excessive pressure drop, generating heat and reducing system efficiency. As a general principle, pressure drop across a fully open directional valve should not exceed 5 bar at nominal flow. Manufacturers publish flow coefficients (Cv or Kv values) that relate pressure drop to flow rate. For a valve with Kv = 8, flowing 80 liters per minute creates approximately 1 bar pressure drop—well within acceptable limits. Doubling the flow to 160 liters per minute quadruples the pressure drop to 4 bar, still acceptable but approaching the threshold where valve sizing should be reconsidered.

Pressure rating directly affects valve construction and cost. Standard industrial valves typically handle pressures to 315 bar, adequate for most mobile equipment and manufacturing machinery. Heavy-duty construction equipment and specialized industrial presses may require high-pressure valves rated to 420-630 bar. The valve body, spool, and seals must all withstand maximum system pressure, including transient pressure spikes that can exceed nominal pressure by 50% or more. Relief valve protection remains essential, but the directional control valve itself must tolerate brief over-pressure events without damage.

Actuation method selection depends on the control system architecture. Manual lever operation suits mobile equipment where the operator directly controls functions. The lever provides tactile feedback and fail-safe operation if electrical systems fail. Solenoid actuation enables remote control and automated sequencing, common in manufacturing systems. Direct-acting solenoids work for smaller valves up to approximately 10 mm spool diameter. Larger valves require pilot-operated solenoids where a small pilot valve controls oil pressure that shifts the main spool. Proportional solenoids offer variable control, with spool position proportional to input current, enabling speed control through flow metering.

Position and center configuration affect both functionality and energy efficiency. Three-position valves provide extend, retract, and neutral functions, suitable for most cylinder control applications. Two-position valves suffice for on-off functions like clamping or simple directional control. The neutral center configuration significantly impacts system behavior. Float center, which connects both work ports to tank in neutral, allows free actuator movement—useful for gravity lowering or manual positioning. However, this configuration provides no holding capability. Closed center blocks all ports, maintaining actuator position but requiring pressure relief elsewhere in the system.

Contamination represents the primary cause of premature directional valve failure. Particulate entering the valve scores the precision surfaces of spools and bores, increasing internal leakage and eventually causing binding. Hydraulic systems operating in construction or agricultural environments face constant contamination threats from dust, water, and mechanical wear particles. Filtration strategies must account for these conditions—10-micron absolute filtration provides adequate protection for most industrial applications, while mobile equipment might require 6-micron or finer filtration to compensate for harsher conditions.

Symptoms of internal valve leakage include slower actuator speeds, gradual load drift, and increased system heat. As clearances between spool and bore increase from wear, pressurized fluid bypasses the intended flow path and returns to tank without performing useful work. The energy lost in this bypass process converts to heat. A valve originally consuming 3 kilowatts at nominal flow might dissipate 8 kilowatts or more with excessive internal leakage. Temperature monitoring provides an early warning—hydraulic oil temperatures consistently exceeding 65°C in light-duty applications suggest efficiency losses requiring investigation.

External leakage typically originates from seal failure or housing cracks. Modern directional valves use O-rings or lip seals at static and dynamic sealing points. Static seals between valve sections and at end caps rarely leak unless damaged during assembly or subjected to over-tightening. Dynamic seals around manually operated spool extensions face more challenging conditions. The reciprocating motion and exposure to environment accelerate wear. Polyurethane seals typically last 50,000-100,000 cycles before requiring replacement, while PTFE-based seals may extend this to 200,000 cycles or more. However, contamination drastically reduces seal life regardless of material selection.

Valve sticking occurs when the spool fails to shift fully or becomes completely immobile. Contamination buildup between spool and bore increases the force required for shifting. In solenoid-operated valves, the solenoid may lack sufficient force to overcome this increased resistance. Varnish deposits from oil degradation can cement the spool in position—a particular problem in systems that sit idle for extended periods or operate at elevated temperatures. Mechanical troubleshooting starts with attempting manual override; most solenoid valves include a push pin that allows manual spool actuation. If the spool moves freely when manually actuated but fails under solenoid power, the solenoid itself warrants investigation. If the spool remains stuck even with manual force, contamination or varnish removal becomes necessary, potentially requiring valve disassembly and cleaning.

The hydraulic valve market reached $5.9-8.8 billion in 2024, with projections indicating growth to $8.6-16.8 billion by 2034, representing a compound annual growth rate of 3.8-6.1%. This expansion reflects increasing industrial automation and infrastructure development globally. North America accounts for approximately 30-38% of the market, driven by construction activity, manufacturing investments, and equipment replacement cycles.

Electro-hydraulic proportional valves have gained market share as automation demands more precise control. Unlike conventional on-off solenoids, proportional valves modulate flow continuously based on input current signals. A proportional valve receiving a 250-milliamp signal might open 25% of full capacity, while 500 milliamps opens it 50%. This capability enables programmable actuator speeds and forces without mechanical adjustments. Manufacturing facilities use proportional valves to optimize production cycles—a stamping press might advance rapidly at low pressure, then slow to high pressure for the forming operation, and finally retract quickly to minimize cycle time. The electrical input profile programs these speed changes without manual valve adjustments.

IoT integration represents an emerging trend in valve technology. Smart valves incorporate pressure, temperature, and position sensors that transmit operational data to maintenance systems. Predictive maintenance algorithms analyze this data to identify developing problems before catastrophic failure occurs. A valve showing gradual increases in operating temperature and response time indicates internal wear, prompting scheduled maintenance rather than emergency repairs. Manufacturers report 20-25% reductions in unplanned downtime when implementing IoT-enabled predictive maintenance compared to traditional time-based service schedules.

Mounting configurations affect both performance and serviceability. Subplate mounting offers the most flexibility for industrial applications. The valve bolts to a standardized subplate that incorporates all port connections. This arrangement allows valve replacement without disturbing hydraulic plumbing—simply unbolt the failed valve and install a replacement. International standards specify port patterns and bolt locations, ensuring interchangeability between manufacturers. SAE J1926 and ISO 4401 define the most common subplate interfaces.

Manifold mounting integrates multiple valves into a single assembly, minimizing space requirements and reducing potential leak points. A manifold might combine three or four directional valve sections with pressure and flow control functions. Internal passages machined into the manifold body replace external plumbing between components. Mobile equipment particularly benefits from manifold construction—a compact integrated valve assembly replaces what might otherwise require dozens of hose assemblies and threaded connections. The trade-off appears in servicing; manifold components can be more difficult to access and require careful reassembly to prevent cross-leakage between passages.

Stack valves extend the manifold concept to modular construction. Individual valve sections bolt together in a stack between inlet and outlet end plates. Each section receives pressure from the previous section and passes it to the next. This arrangement allows easy customization—adding or removing sections changes the number of controlled functions without redesigning the entire valve assembly. Agricultural tractors commonly use stack valves for implement control, with 2-6 sections depending on tractor size and intended applications.

Circuit design profoundly affects valve performance and system efficiency. Series circuits route flow through multiple valves sequentially. The pump must overcome the cumulative pressure drop of all valves in the series, even when only one function operates. Parallel circuits provide independent flow paths, but require flow-dividing mechanisms to ensure each branch receives appropriate flow. Load-sensing systems offer a compromise, adjusting pump output to match actual demand and routing flow only to active functions. Load-sensing compatible directional valves incorporate integral pressure-compensating elements that maintain constant flow regardless of load pressure variations.

A hydraulic system’s efficiency depends largely on how well valve selection and circuit design match the application. Continuous advancement in valve technology provides increasingly sophisticated tools for flow management, yet fundamental principles remain consistent. Understanding port configurations, construction types, and center characteristics enables informed valve selection. Proper filtration, temperature control, and contamination prevention protect this investment, ensuring reliable flow control throughout the equipment’s service life.

A 3-way valve has three ports (pump, work, and tank) and typically controls single-acting cylinders or performs switching functions. The 4-way valve adds a second work port, enabling control of double-acting cylinders by independently pressurizing either side while exhausting the opposite side. The 4-way configuration dominates general hydraulics because most actuators require bidirectional control.

Calculate the required flow by multiplying the actuator’s speed requirement by its effective area. A cylinder with 50 cm² piston area moving at 10 cm/second requires 500 cm³/second or 30 liters/minute. Select a valve rated at least 20% above this calculated flow to account for valve pressure drop and provide margin for system variations. Undersized valves generate excessive heat and reduce actuator speed.

Internal leakage in the directional valve allows pressurized fluid to bypass from one work port to the other or to tank. As valve components wear, clearances between spool and bore increase, raising the leakage rate. Vertical cylinders holding suspended loads exhibit drift most noticeably. Adding pilot-operated check valves at the cylinder ports prevents drift by mechanically locking the cylinder when the directional valve is neutral, though this addresses the symptom rather than the underlying valve wear.

No, hydraulic and pneumatic valves require different designs despite superficially similar functions. Hydraulic valves tolerate the close clearances between spool and bore that minimize leakage but would bind if exposed to moisture or particulate in compressed air. Pneumatic valves use wider clearances and often incorporate different seal materials suited to air rather than oil. Additionally, pneumatic systems typically operate at 6-10 bar while hydraulic systems run 150-250 bar, requiring dramatically different pressure ratings and construction.

Moving into practical application requires matching valve capabilities to actual system demands. The relationship between valve characteristics and machine performance becomes clear through testing under real operating conditions, where theoretical calculations meet the complexities of load variations, temperature changes, and operator inputs.