Menu

Directional hydraulic control valves operate effectively under system pressures ranging from 2,000 to 5,000 PSI in standard industrial applications, with specialized variants handling up to 10,000 PSI in demanding environments. These valves manage pressurized hydraulic fluid flow by directing it through specific pathways using internal spools or poppets that withstand continuous pressure loads while switching between positions. The valve’s pressure-handling capacity depends on port configuration, with pump (P) and work (A, B) ports typically rated higher than tank (T) ports, and proper pressure management prevents cavitation, fluid hammer, and premature component failure.

The relationship between system pressure and valve performance determines hydraulic system reliability. When pressurized fluid enters through the pump port, it creates force against the valve’s internal elements that must be overcome during switching operations.

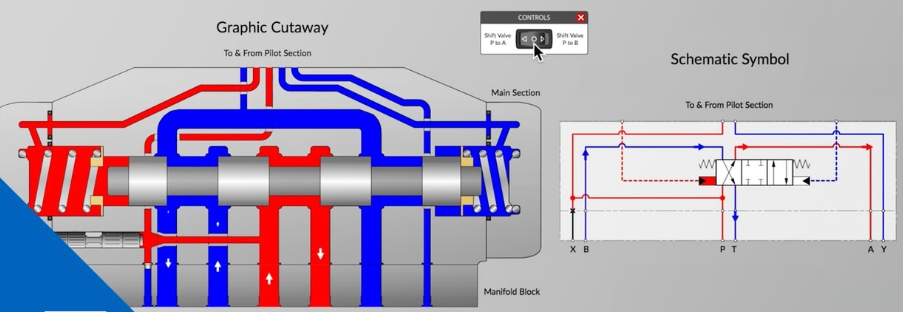

Pressure influences three critical valve functions. First, it affects shifting force requirements – higher system pressure demands greater actuation force to move the spool or poppet against the pressurized fluid. Direct-operated solenoid valves typically max out at 20 GPM flow and moderate pressures because solenoid force limitations make them impractical for high-pressure, high-flow applications. Pilot-operated valves solve this by using small pilot pressure (typically 50-75 PSI) to shift larger spools handling the main system pressure.

Second, pressure creates flow resistance through the valve body. Research from 2024 shows that pressure drop increases proportionally with flow rate but remains independent of absolute system pressure. A valve designed for 200 bar operating pressure and 80 LPM flow exhibits minimal pressure drop under these conditions, but the drop increases significantly when flow exceeds design specifications. The flow coefficient (Cv) quantifies this relationship – a valve with Cv of 1,000 will pass 569.7 GPM with only 0.3193 PSI pressure drop.

Third, sustained pressure affects seal integrity and component wear. Valves running continuously at maximum rated pressure experience accelerated wear on seals, spools, and internal surfaces. Continental Hydraulics D03 pattern valves, for instance, rate P, A, and B ports to 5,000 PSI for continuous duty but limit the T port to 3,000 PSI. This differential exists because tank ports handle lower pressure returns and don’t require the same structural reinforcement as pressure ports.

Port pressure ratings vary based on valve size and mounting standard. NFPA D03 (ISO 4401-03) valves, the smallest common industrial size, typically handle up to 5,000 PSI on working ports with nominal flows to 20 GPM. Moving up, D05 (ISO 4401-05) valves maintain 4,600 PSI pressure ratings with flow capacities reaching 38-40 GPM.

Larger valves scale differently. D07 pattern valves handle 5,000 PSI working pressure with 80 GPM flow, while D08 configurations manage 125 GPM at the same pressure rating. The largest standard industrial valves, D10 pattern, can process 290 GPM while maintaining 5,000 PSI working pressure on P, A, and B ports.

Tank port pressure ratings consistently run lower than working ports across all valve sizes. This design choice reflects the operational reality that return fluid to the reservoir operates at near-atmospheric pressure in most circuits. When backpressure exists in tank lines – from long return runs, undersized plumbing, or flow controls downstream – it can create problems. Excessive tank line backpressure can prevent proper spool shifting in pilot-operated valves, cause sluggish response, or even prevent valve operation entirely.

Mobile hydraulic applications demand different pressure characteristics. Mobile valves operating in construction equipment, agricultural machinery, and mining vehicles face continuous pressure cycling, vibration, and contamination. These valves typically rate to 4,000 PSI continuous duty with burst pressure ratings 50% higher. The Danfoss DG4V series for mobile applications includes IP69K-rated connectors specifically for high-pressure washdown environments common in construction and agriculture.

The pressure rating also connects to valve construction materials. Cast iron bodies dominate industrial applications for their durability and pressure resistance. Steel housings appear in higher-pressure applications, while aluminum construction suits lower-pressure pneumatic systems. Internal components use hardened steel spools with hard chrome or nickel plating to resist wear under pressure-induced friction.

System pressure creates several distinct failure mechanisms that technicians must understand for effective maintenance.

Cavitation occurs when pressure at the valve’s vena contracta – the point of minimum cross-sectional area inside the valve – drops below the fluid’s vapor pressure. This pressure dip results from increased velocity as fluid squeezes through restricted passages. When downstream pressure then rises above vapor pressure, the vapor bubbles collapse violently, releasing energy that erodes metal surfaces. The characteristic “marbles in a can” sound indicates cavitation damage in progress. Proper valve sizing prevents cavitation by ensuring flow velocity stays within design limits.

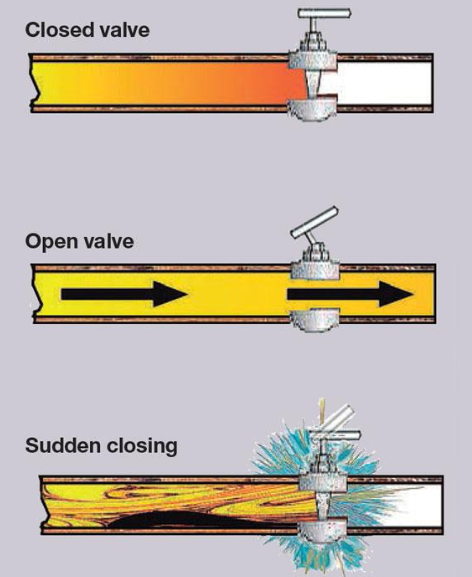

Fluid hammer results from rapid valve closure under pressure. When a valve shuts instantly, the moving fluid column’s momentum creates a pressure spike that can exceed system design pressure by 300-500%. This shock wave propagates through the system, potentially rupturing hoses, damaging seals, or cracking valve bodies. The “bang-bang” characteristic of directional control valves – referring to their instantaneous switching from fully open to fully closed – makes them susceptible to fluid hammer when operating at high flow rates. Proportional valves mitigate this by ramping valve opening and closing, allowing fluid momentum to dissipate gradually.

Pressure-induced seal failure progresses through predictable stages. Initially, high pressure causes elastomer seals to extrude into clearances between spool and bore. This extrusion accelerates when contamination creates scoring on mating surfaces, enlarging clearances. Eventually, the seal fails completely, causing internal leakage that reduces system efficiency and allows pressure to equalize across ports when it shouldn’t. Systems operating continuously near maximum pressure ratings experience seal failures 40-60% sooner than systems running at 70% of rated pressure.

Spool binding represents another pressure-related failure. Contaminants combined with pressure-induced forces can cause the spool to stick in position or move sluggishly. This manifests as slow or incomplete shifting, directional control problems, or complete valve lock-up. Preventive measures include proper filtration (25 micron nominal minimum), maintaining fluid viscosity within specifications (60-1360 SUS), and keeping hydraulic oil clean, cool, and dry.

Effective pressure control requires understanding how valves interact with other system components under pressure.

Relief valves protect directional control valves from pressure spikes by limiting maximum system pressure. Set typically 10-15% above normal operating pressure, relief valves crack open when pressure exceeds the setpoint, routing flow back to the reservoir. The relief valve location matters – positioned between the pump and directional valve, it protects the entire circuit. In fixed-displacement pump systems, the relief valve handles full pump flow when the directional valve centers, creating heat that must be managed through adequate reservoir sizing and potentially supplemental cooling.

Pressure-reducing valves create lower pressure zones within higher-pressure systems. When a directional control valve controls actuators requiring different pressures, a pressure reducer downstream of the directional valve drops pressure to the required level. This arrangement appears frequently in systems where delicate operations share hydraulics with high-force functions.

Pilot pressure supply requires attention in pilot-operated directional valves. These valves need minimum pilot pressure – typically 50-75 PSI – to shift the main spool reliably. Systems drawing pilot pressure from the main pump line normally have adequate pressure, but circuits with unloading or low-pressure conditions during certain operations may starve the pilot circuit. Dedicated pilot pumps solve this in critical applications.

Pressure compensation maintains consistent actuator speed regardless of load pressure. Pressure-compensated flow controls ahead of directional control valves adjust their restriction based on differential pressure, ensuring consistent flow to the actuator. This prevents the common problem where cylinder speed varies with load, particularly problematic in precision positioning applications.

Center position configuration affects pressure behavior significantly. In closed-center configurations, all ports block when the valve centers, trapping pressure in the actuator lines. This holds cylinders in position under load but requires a relief valve to protect the pump. Open-center valves route pump flow directly to tank in neutral, unloading the pump but allowing actuators to drift under external forces. Tandem center positions block work ports while connecting pump to tank – ideal for fixed-displacement pumps needing unloading but requiring actuator position holding. Float centers connect both work ports to tank while blocking pump flow, allowing free actuator movement while maintaining pump pressure for other circuits.

Matching valve specifications to system pressure requirements determines long-term reliability and efficiency.

Continuous vs. intermittent pressure ratings appear on some valve specifications. Continuous duty pressure represents the maximum pressure the valve can handle indefinitely without degradation. Intermittent or peak pressure ratings indicate brief pressure spikes the valve can withstand without damage. For example, a valve rated 4,600 PSI continuous and 5,500 PSI intermittent can handle pressure spikes during shock loading or thermal expansion but shouldn’t operate at 5,500 PSI for extended periods.

Pressure drop through the valve consumes system power and generates heat. Lower pressure drop means more available pressure at the actuator and better system efficiency. Manufacturers publish pressure drop curves showing how drop increases with flow rate. A well-sized valve operates in the lower portion of these curves – typically achieving less than 50 PSI drop at normal flow rates. Operating in the high pressure drop region (>150 PSI drop) indicates the valve is undersized for the application.

Temperature affects pressure-handling capacity through its impact on seal materials and fluid viscosity. High-pressure operations generate heat through friction and fluid compression. This heat degrades seals faster at elevated temperatures – Viton seals maintain performance to 400°F but standard Nitrile compounds deteriorate rapidly above 200°F. The 2024 Danfoss industrial valve line offers Viton seals as standard specifically for high-temperature, high-pressure applications where Nitrile would fail prematurely.

Mounting style influences pressure capability. Manifold-mounted valves distribute pressure loads through the manifold structure, allowing compact packaging of multiple functions while maintaining high pressure ratings. Surface-mounted valves with subplates require proper installation torque and flat mounting surfaces to seal effectively under pressure. A 0.002-inch gap under a subplate can allow high-pressure fluid to blow out the seal, even in properly rated components.

Systematic pressure testing identifies developing problems before catastrophic failure.

Proof pressure testing verifies valve integrity at 1.5 times rated pressure for a specified duration, typically 60 seconds. This test confirms the valve housing can withstand pressure excursions without rupture. Manufacturers conduct proof testing during production, but field testing after repair or suspected damage validates continued structural integrity.

Leakage testing under pressure reveals internal seal condition. Across-port leakage measures fluid seeping past spools from pressure to work ports or from work ports to tank when the valve should fully block these paths. Excessive leakage degrades system performance – a cylinder creeping under load or speed inconsistency often traces to directional valve leakage. Acceptable leakage rates vary by valve type and size, but exceeding manufacturer specifications by 50% typically warrants valve replacement or rebuild.

External leakage around seals, manifold joints, or through drain ports indicates different problems. Unlike internal leakage, external leaks waste fluid, create safety hazards, and signal imminent failure. High system pressure accelerates external leakage as pressure forces fluid through any available path. Regular inspection catches weeping seals before they blow out completely under pressure.

Pressure monitoring during operation identifies abnormal conditions. Pressure gauges at key points show whether the system maintains expected pressures during all phases of the work cycle. A gauge upstream of the directional valve reading below normal during actuation suggests valve restriction or pump problems. Downstream gauges showing unexpected pressure during valve centering indicate leakage allowing pressure to transfer where it shouldn’t.

Contamination control protects valves operating under pressure. Particles larger than clearances between spools and bores (typically 0.0002-0.0005 inches) cause scoring, stuck spools, and seal damage. High pressure accelerates contamination damage by forcing particles into small clearances and grinding them against surfaces. Beta ratios indicating filtration efficiency – beta 75 = 3 micron removes 98.7% of particles 3 microns and larger – determine filter selection. Most directional control valve manufacturers specify beta 75 = 10 micron (which removes 98.7% of particles 10 microns and larger) as minimum for valves operating above 3,000 PSI.

Different industries leverage pressure capabilities of directional control valves for specific demands.

Construction equipment relies on high-pressure directional control valves for power density. An excavator’s swing function might use D05 valves rated 4,600 PSI handling 35-40 GPM flow to control a 50,000 lb machine. The high pressure allows smaller cylinders and motors, reducing weight while maintaining force output. These valves face continuous pressure cycling – extending and retracting hundreds of times daily – requiring robust construction and seal designs that maintain performance through millions of cycles.

Mining applications push pressure limits further. Underground mining equipment operates in explosive atmospheres requiring ATEX/IECEx certified valves. These valves maintain pressure ratings while incorporating design features that prevent sparks or hot surfaces. Continuous Hydraulics valves certified for use in explosive atmospheres maintain 5,000 PSI ratings with specialized electrical connections and surface treatments ensuring 600-hour salt spray resistance for corrosive mining environments.

Manufacturing automation demands different pressure characteristics. Assembly line equipment requires precise, repeatable motion at moderate pressures. Directional control valves in these applications typically operate 1,500-2,500 PSI with proportional control allowing speed ramping and smooth acceleration. The lower pressure extends component life and reduces noise, important factors in factory environments. However, the valves must maintain pressure consistently to ensure position repeatability within 0.1-0.5mm.

Agriculture combines the worst of all environments – high pressure, contamination, vibration, temperature extremes, and weather exposure. Tractor implements use directional control valves controlling functions from bucket tilt to row marker deployment. These valves must operate reliably at 3,000-3,500 PSI while contaminated with dust, mud, and crop residue. Mobile valve designs with IP69K protection allow high-pressure washdown without allowing water ingress that would destroy internal components.

Valve body material strength, internal component design, and seal specifications determine maximum pressure capability. Most industrial valves use cast iron bodies that safely handle 5,000 PSI continuous pressure on working ports. Larger valves may use steel housings for enhanced strength. The limiting factor is often seal technology rather than housing strength – elastomer seals fail through extrusion or degradation before the metal housing yields.

Tank ports connect to the reservoir at near-atmospheric pressure in normal operation, so they don’t require the same structural reinforcement as high-pressure working ports. This allows manufacturers to optimize weight and cost by using thinner walls and fewer material in tank port areas. However, excessive backpressure from restricted tank lines can cause problems if it approaches the lower tank port rating.

Pressure drop consumes system power and converts it to heat without doing useful work. Every 50 PSI lost through excessive valve restriction reduces available pressure at the actuator, slowing operation or reducing force output. The wasted energy becomes heat that must be dissipated through the reservoir, potentially requiring supplemental cooling in high-flow systems. Properly sized valves minimize pressure drop while maintaining adequate flow capacity.

Brief pressure spikes above rated pressure occur normally during shock loading or thermal expansion. Most valves withstand these momentary excursions up to 150% of continuous rating. However, sustained operation above rated pressure dramatically shortens seal life and risks catastrophic failure. The valve housing might withstand the pressure, but seals fail rapidly, leading to internal leakage and loss of control. Always maintain working pressure within continuous duty ratings for reliable long-term operation.

The hydraulic directional control valve market reached $5.89 billion in 2024 and shows projected growth to $8.56 billion by 2034, driven by expanding automation and construction sectors globally. This growth reflects the critical role these valves play in managing pressurized fluid systems across diverse industrial applications. Understanding pressure dynamics separates reliable systems from premature failures, making proper valve selection and maintenance essential for operational success.

Recommended internal link opportunities: hydraulic system design fundamentals, pressure relief valve sizing, contamination control strategies