Menu

We get calls about hydraulic press control upgrades almost every month. The question is almost always the same: “Should I switch from solenoid valves to electric motorized valves?” And honestly, most people asking don’t really know what they’re choosing between. They just know the current system isn’t cutting it anymore—cycle times are inconsistent, energy bills keep climbing, or maintenance is eating into production hours.

Here’s the thing though. When you get this decision right, the payoff is real. We’ve seen plants cut their per-cycle energy consumption by 15-20% just by matching the right valve type to their actual operating profile. One injection molding shop we worked with last year shaved 0.3 seconds off every clamping cycle after switching from on-off solenoids to proportional control. Doesn’t sound like much until you multiply it by 800 cycles a day, 300 days a year. That’s 2,000+ hours of recovered capacity over the equipment’s lifetime.

So yeah, this stuff matters. Let’s get into it.

A solenoid valve is basically a magnetic on-off switch for fluid. You run current through a coil, it creates a magnetic field, that field yanks a metal plunger, and boom—port opens. Kill the power, spring kicks it back closed. The whole thing happens in maybe 20-30 milliseconds. Fast.

But here’s what trips people up: standard solenoid valves are binary. Open or closed. Nothing in between. It’s like a light switch that only does ON and OFF—no dimmer function. One of our field engineers likes to call it “the sledgehammer approach.” Works great when you just need to start and stop flow. Not so great when you need finesse.

Our take on this: binary control gets a bad rap sometimes, but honestly? It covers maybe 70% of industrial valve applications just fine. Clamping, directional switching, safety interlocks, emergency shutoffs—these don’t need intermediate positions. They need fast, reliable, predictable. A solenoid that’s worked for 15 years isn’t broken just because newer options exist.

Where it becomes a limitation is when you see operators trying to “tune” a process using fixed orifices, throttling valves, or software workarounds to fake flow modulation. That’s the system fighting itself. When process stability or material quality depends on gradual transitions—ramping pressure up slowly, controlling deceleration—binary control starts working against you. At that point, you’re not solving a valve problem anymore. You’re solving a control resolution problem.

Electric motorized valves work completely differently. There’s an actual motor in there—usually a stepper or small servo—that physically rotates or pushes the valve element to whatever position you command. Want 47% open? You got it. Need to ramp from 20% to 80% over 3 seconds? No problem.

The trade-off? Speed. Where a solenoid snaps open in 20 milliseconds, your typical electric ball valve takes 5-10 seconds to go full stroke. That’s roughly 250x slower. For high-speed cycling applications, that’s a dealbreaker. For HVAC or process control where you’re making gradual adjustments? Totally fine.

Alright, let’s look at actual specs. The table below pulls from manufacturer datasheets we’ve collected over the years—Danfoss, Parker, Bosch Rexroth, some domestic suppliers. These are typical ranges, not guarantees for any specific model.

| What You’re Measuring | Solenoid Valve | Electric Motorized Valve |

| Response Time | 10-50 ms | 2-15 seconds |

| Control Type | Binary only (on/off) | Variable (any position 0-100%) |

| Pressure Rating | Up to 350 bar (5,000 psi) | Usually maxes at 100 bar |

| Power Draw | 5-30W continuous while energized | Only during movement |

| Expected Lifespan | 1-10 million cycles | 50,000-100,000 cycles |

| Unit Cost | $50-$800 | $150-$2,000 |

| What Happens on Power Loss | Springs back to default position | Stays where it is (needs spring return for fail-safe) |

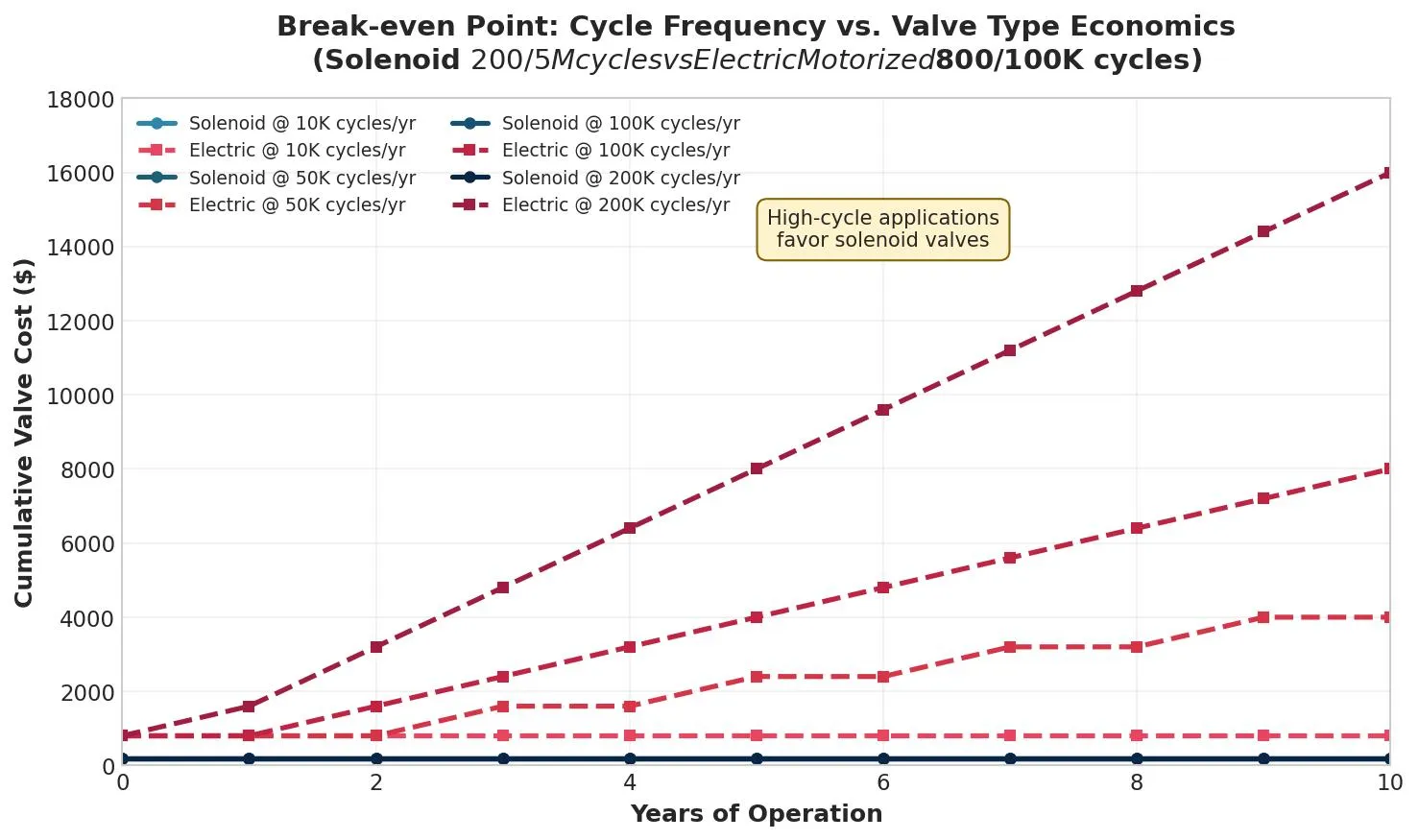

What the table tells us: Look at that cycle life difference. Solenoid valves can handle 10 million cycles—that’s roughly 27,000 cycles a day for a year straight. Electric motorized valves top out around 100,000. If your application cycles more than a few hundred times daily, the math on replacement costs shifts dramatically.

Now, that response time gap—10-50 milliseconds vs. 2-15 seconds—might seem abstract. Let me put it differently. In the time it takes an electric valve to fully open once, a solenoid could cycle 300+ times. For injection molding, stamping presses, packaging lines—anywhere timing is measured in fractions of seconds—solenoids are the only real option.

There’s a third option that often gets overlooked: proportional hydraulic valves. These use a special solenoid design where the force output scales with input current. Feed it 4mA, you get a little movement. Feed it 20mA, you get full stroke. Everything in between gives you, well, everything in between.

Response times typically land around 20-100 milliseconds—not quite as fast as basic solenoids, but way faster than motorized valves. And you get that variable positioning capability that on-off solenoids can’t touch.

Danfoss recently launched their AxisPro line and made a point about the shift happening in the industry: these valves now come with built-in support for Ethernet/IP, EtherCAT, and other industrial protocols. That’s not just a spec bump—it signals where hydraulic system upgrade projects are heading. More connectivity, more data, tighter integration with plant-level systems.

Real talk from our side: proportional valves aren’t a universal upgrade. They shine when variable control directly impacts product quality, machine longevity, or operator safety—think smooth motion profiles that reduce shock loads, or running multiple product variants on the same equipment without hardware changes. If your control system already speaks 4-20mA or fieldbus, the integration is straightforward.

But we’ve also seen plenty of projects where proportional control was overkill. Fixed operating points, wide process tolerances, limited PLC capability—in those cases, the added cost, tuning effort, and commissioning time never get recovered. We usually ask customers to validate whether the process truly requires continuous modulation, or whether a well-selected on-off valve with proper circuit design gets the job done more reliably.

Rather than list out generic “use cases,” let me walk through some actual project scenarios we’ve dealt with. Names changed, but the technical details are real.

The plastics manufacturer who wanted “better precision”

500-ton injection molding machine, running standard on-off solenoids for clamping control. Their complaint: inconsistent clamping force was causing flash on parts and occasional short shots. Initial instinct was to go electric motorized for “more precise control.”

Bad idea. Why? The clamping sequence needs to complete in under 200 milliseconds. Electric valves would’ve added 5+ seconds to every cycle. Instead, we specced proportional directional valves with position feedback. Response time stayed under 80ms, but now they could program force profiles—soft start, full clamp, hold, soft release. Flash problems disappeared.

Cost difference? The proportional setup ran about 4x the price of their original solenoids. But they were already losing 2-3% of output to defects. ROI hit within 6 months.

The building manager with the chiller system

Completely different story. Commercial building, 15-year-old chilled water distribution. They were using manual valves for zone control—maintenance guy literally walking around adjusting things. Wanted automation.

Here, electric motorized ball valves made total sense. Pressure was under 10 bar, actuation speed didn’t matter (HVAC loads change over minutes, not milliseconds), and they needed BACnet integration with the building automation system. We went with 2-inch motorized valves, analog positioning, built-in manual overrides for when the automation acts up. Nobody cares that they take 8 seconds to open.

The OEM designing a compact excavator

This one pushed into all the hard requirements at once: boom/arm/bucket control needed variable flow for smooth operation, but also shock resistance, wide temperature range (-30°C to +80°C), and IP67 protection because, well, it’s an excavator. Plus the operators expect responsive joystick control—you move the stick, the bucket moves now, not 3 seconds from now.

Electric motorized valves were out immediately—couldn’t handle the shock loads or pressure requirements. Simple solenoids would’ve given jerky, on-off boom movements. The answer was mobile-rated proportional directional valves with integrated electronics. Expensive? Absolutely. Necessary? Also yes.

Purchase price is the easy number. The harder numbers come later.

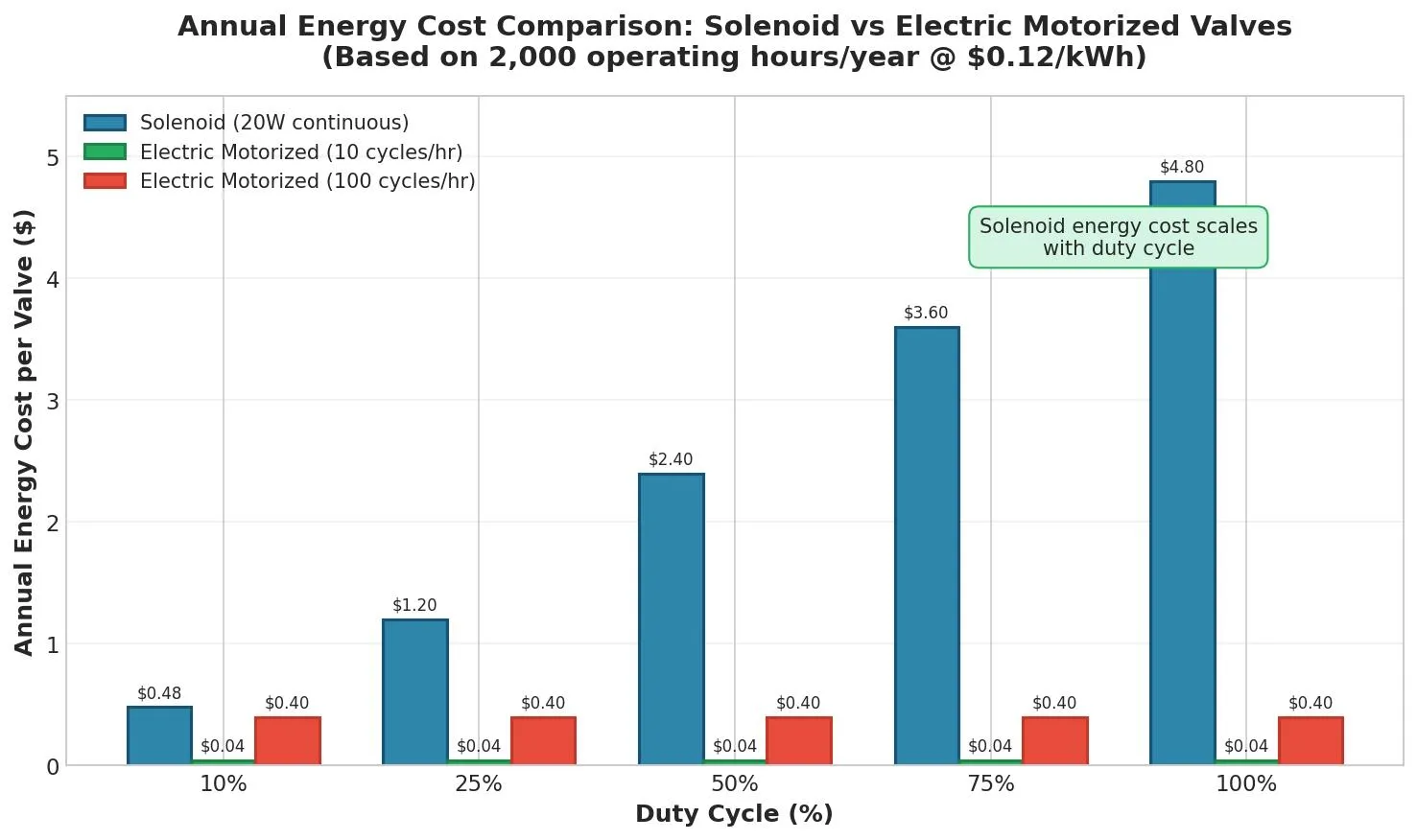

Take energy. A 20-watt solenoid running 8 hours a day, 250 days a year, at $0.12/kWh costs you about $4.80 annually. Sounds like nothing. But scale it: 50 solenoids across a plant? That’s $240/year just in holding current. Over 10 years, $2,400. Still not huge, but not nothing either.

Electric motorized valves only draw power during actuation. If you’re positioning a valve once every few minutes, annual energy cost might be under a dollar per valve.

But energy isn’t where the real cost difference hides. It’s in replacement cycles.

Let’s say your application runs 50,000 cycles per year. A solenoid rated for 5 million cycles lasts 100 years (theoretically—other components will fail first). An electric motorized valve rated for 100,000 cycles needs replacement every 2 years. If that motorized valve costs $800 and the solenoid costs $200, you’re spending $400/year on motorized valve replacements vs. essentially $0 on solenoids for the foreseeable future.

How we usually walk customers through this: forget component-level comparisons. Model it at the application level. How often does this valve actually cycle? What’s the real duty profile? What does an unplanned failure cost you—not just the part, but the downtime, the rush shipping, the weekend overtime to get production back online?

For high-cycle applications, simplicity and durability usually dominate the math. For low-cycle, high-value processes—think precision assembly or batch chemical dosing—energy efficiency and control accuracy can outweigh the component price difference entirely. The answer changes depending on where you’re standing.

Honestly? Start with three questions:

After those basics, you get into system-specific factors: pressure requirements (solenoids handle higher), space constraints (solenoids are usually more compact), fail-safe needs (solenoids spring back, motorized valves hold position), and control system interface (what signals can your PLC actually output?).

For hydraulic valve selection on complex projects, we usually recommend walking through your P&ID and asking these questions for each valve location individually. Different points in the system often have different requirements.

One more thing worth mentioning: standard catalog valves don’t always fit. We see this constantly with OEM accounts especially—they need a specific port configuration, a non-standard voltage, special materials for aggressive fluids, whatever. That’s where working with a supplier who can do custom hydraulic configurations in-house makes a real difference. You’re not stuck trying to adapt a close-enough product or playing telephone between the valve manufacturer and a third-party machine shop.

Quick installation notes since we see the same mistakes repeatedly: Mount solenoid valves coil-up when you can—prevents fluid pooling if seals degrade. Use surge suppressors on solenoid circuits; the inductive kickback when you de-energize can fry PLC outputs. For motorized valves, verify your actuator torque rating exceeds your maximum expected operating torque by at least 25%—undersized actuators stall when valve components get sticky.

Fluid cleanliness matters more than most people realize, especially for solenoids. A 10-micron particle sounds tiny—it’s about 1/7th the width of a human hair—but it’s big enough to prevent a plunger from seating properly. Suddenly you’ve got internal leakage, pressure drops, and a valve that “sort of works” but not reliably. Good filtration upstream of your solenoid valves isn’t optional.

One trend worth tracking: smart valves with embedded diagnostics. Both solenoid and motorized valves are increasingly available with IO-Link or fieldbus connectivity. They report cycle counts, operating temperature, position feedback. For plants moving toward predictive maintenance, this data is gold—you know a valve is degrading before it fails.

Premium for smart features runs about 20-40% over basic models. Whether that’s worth it depends entirely on what a surprise valve failure costs you in downtime.

We had a customer last year—automotive stamping plant—who resisted the upcharge on IO-Link solenoids for their main press line. Six months later, a valve stuck mid-cycle. Damaged tooling, 14 hours of unplanned downtime, somewhere around $180,000 in total impact. The IO-Link version would’ve flagged the degrading response time weeks earlier. Sometimes the “premium” is actually insurance.

The hydraulic solenoid valve vs electric valve question doesn’t have a universal right answer. Solenoids win on speed, cycle life, and high-pressure capability. Electric motorized valves win on variable positioning, large flow capacity, and quiet operation. Proportional hydraulic valves split the difference when you need both responsiveness and modulation.

The decision framework is straightforward: match the valve capability to your actual application requirements, then verify the economics work over the equipment’s expected lifetime. If you’re working through a hydraulic system upgrade and the choice isn’t obvious, that’s usually a sign you should be talking with someone who’s seen a lot of these projects. Our team has been speccing hydraulic systems for 25+ years across every industry you can name—we’re happy to talk through specific situations.

Most valve selection issues we run into aren’t caused by wrong specs—they’re caused by unclear process priorities. Before we recommend anything specific, we usually start with a short technical conversation focused on how the system actually operates, not what’s currently bolted on.

What does the system need to do? Which parameters actually affect throughput or quality? Where do you need variability versus consistency? What constraints exist in controls, space, environment, maintenance access? Whether the final answer is a standard solenoid, proportional control, or a custom-engineered assembly, starting from application context keeps things from getting overcomplicated.

Heads up: Specs and cost estimates in this article are based on typical industry values from multiple manufacturers. Your mileage will vary depending on specific models, operating conditions, and application requirements. Before making purchasing decisions, get actual quotes and verify specs against your system parameters. If you’re unsure, ask.