Menu

I’ll be straight with you – we’ve been selling and specifying hydraulic check valves for nearly 15 years now, and the number of times I’ve seen engineers spec the wrong valve because they misread a schematic is… well, let’s just say it’s more than I’d like to admit.

The hydraulic check valve symbol might look simple on paper (literally just a ball with a spring and a line, right?), but there’s a hell of a lot more going on when you’re dealing with high-pressure applications. And trust me, getting it wrong in a 350-bar system is not something you want to experience firsthand.

Before we get into the technical stuff, here’s something that happened to us back in 2019. Customer calls in, absolutely frantic – their mobile crusher has gone down on a site in Queensland. They’d installed what they thought was a pilot-operated check valve based on the circuit diagram. Turns out? Different manufacturer, different symbol convention. Cost them three days of downtime and about £8,000 in lost revenue.

That’s when we started being really pedantic about symbol standardisation with our clients.

The thing is, hydraulic check valve symbols aren’t quite as universal as everyone thinks they are. ISO 1219-1 gives us the standard symbols, sure. But then you’ve got American manufacturers who sometimes use ANSI standards, and don’t even get me started on some of the older European equipment manuals we’ve seen.

Right, basics first.

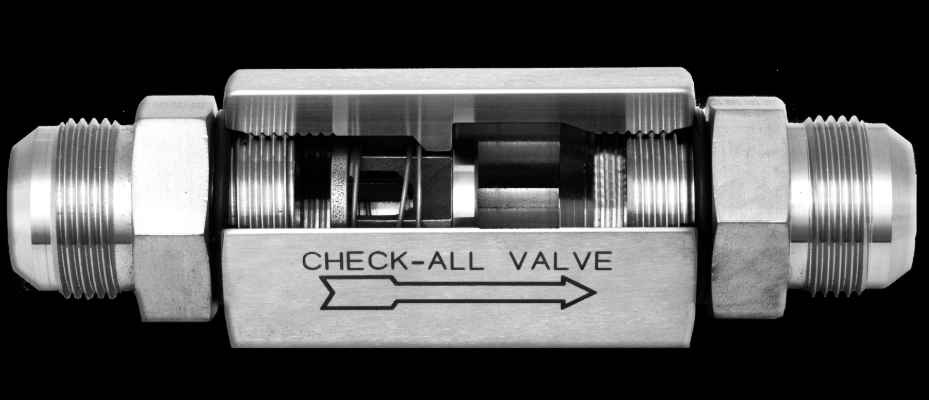

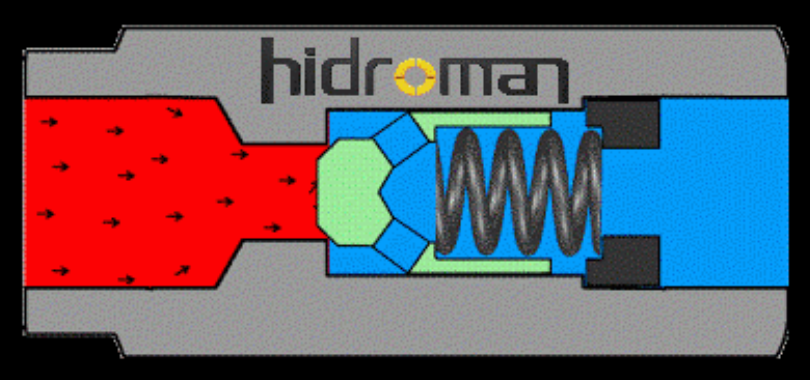

Your standard check valve symbol is a circle (or sometimes a ball) with a spring behind it and a line showing the flow direction. Flow goes one way freely, tries to go back the other way, and – bang – the valve seats and blocks it.

![Standard check valve symbol representation]

Free flow direction → The open side where fluid passes through easily

Blocked flow direction ← Where the spring-loaded element prevents reverse flow

Simple enough when you’re looking at a 50-bar system running at 15 litres per minute. But crank that up to 420 bar in a press application? The symbol stays the same, but everything else changes.

We stock inline check valves from Parker, Bosch Rexroth modular checks, and about a dozen other manufacturers, and I can tell you – they all draw their symbols slightly differently in their catalogues. The ISO symbol is consistent, but the manufacturer’s technical drawings? That’s where it gets interesting.

Here’s what the symbol doesn’t tell you: at high pressure, you need to start thinking about cracking pressure, reseat pressure, and whether your check valve is actually going to seal properly when things get serious.

Last month we had a spec query for a forestry application – 380 bar working pressure, thermal loads all over the place because it’s running in Canadian winters. The engineer just drew a standard check valve symbol on the schematic. We had to have a proper conversation about whether he needed a poppet-style or a ball-style valve, what the thermal expansion characteristics were, and whether the spring was going to fatigue under those conditions.

The symbol? Same as always. The valve specification? Completely different beast.

When we’re quoting high-pressure check valves (and by high-pressure, I mean anything north of 250 bar), here’s what we’re looking at:

Cracking pressure – This is the minimum pressure needed to open the valve. At high pressures, you want this optimised. Too low and you get flutter and cavitation. Too high and you’re wasting energy. We typically see 0.5 to 2 bar cracking pressure specified, but it’s application-dependent.

Reseat capability – Can the valve actually close fast enough when flow reverses? In high-pressure systems with rapid directional changes, this is critical. I’ve seen valves that work perfectly fine at 150 bar completely fail to reseat properly at 350 bar because the spring wasn’t specced correctly.

Material selection – The symbol doesn’t tell you if it’s hardened steel, if the seat is nitrided, or if you’ve got polyurethane seals that are going to fail in three months. For high-pressure work, we almost always recommend hardened steel poppets with NBR or FKM seals depending on the fluid.

Pilot operation – Sometimes you’ll see a dotted line on the symbol indicating pilot operation. THIS IS IMPORTANT. Pilot-operated checks are essential for holding loads in vertical applications, and the symbol variation is subtle but critical.

Now this is where it gets practical. Different symbols, different valves, different applications.

The basic spring-loaded check. One-way flow. Dead simple on paper, works great for return lines, suction lines, and low-criticality applications.

We sell hundreds of these every month – mostly Casappa inline checks and Hydac sandwich checks. They’re workhorses.

This one has an additional dotted line running to the valve – that’s your pilot line. The valve stays closed until it receives a pilot signal, then it can open in both directions.

These are brilliant for vertical cylinders – think: hydraulic presses, tipper trucks, mobile elevators. Without pilot operation, you get drift. With it, your load stays exactly where you put it, even at 400 bar.

We’ve supplied these to marine applications where the last thing you want is a hydraulic stabiliser drifting while you’re in rough seas.

Sometimes you’ll see a small arrow through the spring symbol – that means the cracking pressure is adjustable. Useful for fine-tuning systems, but honestly? We don’t see these specified that often anymore. Most modern valves come pre-set from the factory at optimal cracking pressures.

Right, here’s where people get mixed up. A counterbalance valve looks similar to a pilot-operated check on a schematic, but it’s doing something quite different – it’s regulating the rate of descent rather than just preventing backflow.

If you put in a check valve where you actually need a counterbalance valve (or vice versa), you’re going to have problems. We’ve had this conversation with customers more times than I can count.

Let me give you some actual examples from systems we’ve worked on, because this stuff makes way more sense with context.

Client: Sheffield-based manufacturer

Application: 1200-tonne hydraulic press

Pressure: 420 bar operating, 450 bar peak

Valves specified: Pilot-operated checks on all vertical cylinders

The schematic showed standard pilot-operated check symbols, but the spec conversation took about two hours because we needed to discuss cycle times, holding requirements, and whether the valves needed load-holding certification. Eventually went with Sun Hydraulics pilot checks because they had the certification documentation the client’s insurance required.

Cost of getting it wrong? If those valves fail to hold, you’ve got 1200 tonnes of potential energy ready to do some serious damage.

Client: Aggregate processing contractor (Australia)

Application: Mobile crushing circuit with multiple functions

Pressure: 350 bar continuous

Challenge: Temperature extremes (-5°C to +45°C ambient)

Standard check valve symbols throughout the schematic, but the environment meant we had to really think about seal materials. Ended up speccing FKM seals instead of standard NBR because the thermal cycling was going to kill standard seals in under a year.

The symbol looked identical to what you’d use on a benchtop test rig. The valve specification was completely different.

Client: North Sea platform operator

Application: Emergency shutdown systems

Pressure: 380 bar with 10-year service intervals

Requirement: Absolute reliability, no exceptions

Every single check valve in that system had to be pilot-operated, had to have documented proof of cyclic testing, and had to meet SIL 3 safety requirements. The symbols on the P&ID were standard ISO 1219-1, but the procurement process took six months because the specification was so tight.

We worked with Bosch Rexroth on that one because frankly, not many manufacturers can provide that level of documentation and traceability.

Alright, here’s the stuff that drives me mental about hydraulic schematics.

The symbol shows you function. It doesn’t show you any of this:

Port sizes – We’ve had customers try to fit 3/4″ BSP valves into circuits designed for 1″ NPT. The symbol looks the same. The threads don’t match.

Flow capacity – A check valve rated for 80 litres/min and one rated for 150 litres/min look identical on a schematic. Install the wrong one and you get pressure drop, heating, and eventually valve failure.

Mounting style – Inline? Sandwich plate? Manifold-mounted? Can’t tell from the symbol, but it makes a massive difference to your system packaging.

Seal material – NBR, FKM, HNBR, polyurethane? The symbol won’t tell you, but your operating temperature range and fluid type sure as hell will.

Certification requirements – Does it need ATEX? Does it need SIL rating? Is it going on a vessel that requires Lloyds Register approval? Symbol doesn’t care. Your insurance company does.

This is why we always insist on a proper specification conversation before we quote anything for high-pressure applications. The symbol gets you started. The spec sheet gets you a valve that actually works.

Mistake #1: Assuming All Check Valves Are the Same

They’re not. We’ve got check valves in our warehouse that range from £12 inline brass checks for low-pressure water systems up to £2,400 pilot-operated cartridge valves for critical load-holding applications. Same basic symbol, completely different performance.

Mistake #2: Ignoring Cracking Pressure

Someone specs a check valve with 3 bar cracking pressure on a 15 bar suction line. Congratulations, you’ve just starved your pump and caused cavitation damage. We’ve seen this exact scenario at least twice this year.

Mistake #3: Wrong Pilot Ratio on POCV

Pilot-operated checks need the right pilot pressure ratio to open reliably. Get it wrong and the valve either won’t open at all, or it cracks open slightly and destroys itself through erosion. The symbol shows a pilot line. It doesn’t show what pilot ratio you need.

Mistake #4: Not Considering Installation Orientation

Some check valves (particularly poppet-style ones) are orientation-sensitive at high pressure. Install them horizontally when they’re designed for vertical mounting and you might get seal extrusion or premature wear.

We literally had a customer send back five valves as “defective” last year. Valves were fine. They’d installed them upside down. Symbol doesn’t show installation orientation.

Here’s something you won’t read in a textbook: different manufacturers draw their symbols differently in their technical literature, and it can cause problems.

Parker tends to use very clean ISO-standard symbols in their catalogues. Great for clarity, but sometimes lacks the detail you need for complex circuits.

Bosch Rexroth often includes additional detail in their symbols – showing pilot ports, drain ports, adjustment features. More complex to read initially, but you get better information.

Sun Hydraulics uses a proprietary symbol system for their cartridge valves that shows cavity information. If you’re used to ISO symbols, it takes a bit of getting used to.

Italian manufacturers (Casappa, Brevini, Vivoil) generally stick close to ISO standards, but watch out for older documentation that sometimes uses pre-ISO conventions.

We’ve been working with all these manufacturers for years, so we can translate between symbol conventions, but if you’re sourcing directly? Double-check what you’re actually ordering.

Right, so you’ve got a schematic in front of you with check valve symbols scattered throughout. How do you actually read this thing when high pressure is involved?

Start with the pressure specification – What’s the system rated for? If you’re looking at 300+ bar, every component in that circuit needs to be rated accordingly. Check valve symbols stay the same, but component selection becomes critical.

Look for pilot lines – Any dotted lines running to check valve symbols? That’s pilot operation, and it usually means load-holding is involved. These valves need extra attention in the specification process.

Count the check valves – If you’ve got check valves in multiple locations doing similar jobs, there’s probably a standardisation opportunity. We often find systems where three different types of check valves are specified when one type could handle all positions.

Check the component list – The symbol tells you function. The component list tells you the actual part number. ALWAYS cross-reference these. We’ve seen schematics where the symbol and the part number don’t match because someone updated one but not the other.

Look at surrounding components – What’s upstream and downstream of each check valve? This context tells you a lot about what that valve is actually doing in the system.

When a customer comes to us with a high-pressure application, here’s our process:

Understand the function – What’s this valve actually doing? Preventing backflow in a return line is different from holding a vertical load is different from isolating a pump.

Establish the pressure parameters – Working pressure? Peak pressure? Pressure spikes? This determines material selection and spring rating.

Flow requirements – Maximum flow rate? We need to make sure the valve can handle it without excessive pressure drop or heating.

Environmental factors – Operating temperature? Ambient conditions? Fluid type? This drives seal selection and material compatibility.

Mounting constraints – Physical space available? Mounting orientation? Port configuration?

Certification requirements – Any industry-specific certifications needed? This can significantly impact valve selection and cost.

Only after we’ve gone through all that do we actually recommend a specific valve. The symbol might be simple, but the specification process isn’t.

I’m going to level with you – most check valve failures we see are specification errors, not manufacturing defects.

Symptom: Valve Won’t Open (or Opens Intermittently)

Possible causes:

We had this exact issue on a press system last year. Customer insisted the valve was faulty. Sent it back to us, we tested it – perfect. Turns out they were running at lower pressure during setup mode, which wasn’t enough to crack the valve open reliably. Solution: adjustable cracking pressure valve or system pressure adjustment.

Symptom: Valve Won’t Close (Leaking Backwards)

Possible causes:

Seen this a lot on systems with poor filtration. A single piece of swarf gets caught in the seat and boom – you’ve got backflow. High-pressure systems are particularly sensitive to this because the velocity is higher and any contamination does more damage.

Symptom: Valve Works But System Performance Is Poor

Possible causes:

This one’s subtle. The valve is technically working, but it’s not right for the application. Usually shows up as slower cycle times or excessive heating.

Interesting development over the last five years: smart check valves with integrated pressure sensors.

Some manufacturers (Parker and Bosch Rexroth are leading this) are now offering check valves with embedded sensors that monitor pressure, temperature, and flow. The symbol is evolving to show sensor outputs, but there’s no standardisation yet.

We’re also seeing more modular cartridge-style checks that can be field-configured for different cracking pressures and flow rates. The symbol stays the same, but the valve can be adapted to different applications without changing the component.

For high-pressure applications, this is actually pretty useful because you can optimise valve performance without redesigning the circuit.

Look, I’m going to give you our actual internal checklist for specifying high-pressure check valves, because I think it’s useful:

Critical Questions:

If we can’t answer all of these questions, we won’t quote a valve. Full stop. Too many ways to get it wrong.

We’re completely independent, which means we can recommend whatever actually works best rather than pushing a single brand. For high-pressure check valves specifically:

Parker – Excellent range of pilot-operated checks, very good technical support, reliable delivery times. We use them a lot for load-holding applications.

Bosch Rexroth – Outstanding quality, particularly their logic valve elements. Pricey, but worth it for critical applications. Their documentation is also some of the best in the industry.

Sun Hydraulics – Specialists in cartridge valves, brilliant for manifold systems. If you’re designing a custom manifold for high-pressure work, Sun is usually our first call.

HydraForce – Good mid-range option, particularly for mobile equipment. Reliable, decent pricing, good availability.

Casappa – Italian quality at sensible prices. Their inline checks are workhorses.

Danfoss – Strong on mobile hydraulics, particularly their PVHC series for pilot-operated checks.

We’ve got direct relationships with about 80 manufacturers total, but for high-pressure checks, those six probably account for 90% of what we supply.

If you’re working on a high-pressure system and you’re not 100% certain about your check valve specification, just call us. It’s free advice, and it might save you a lot of money and aggravation down the line.

We’ve been doing this since 2009, we’ve seen pretty much every possible application, and we can usually tell you within ten minutes whether your specification is sound or needs adjustment.

We ship to 130 countries, we hold massive stock, and we can usually get valves to you within 48 hours if it’s urgent.

Can I use a standard check valve in a 400-bar system?

Depends entirely on the valve. Some standard checks are rated to 420 bar, others max out at 210 bar. You need to check the manufacturer’s data sheet. Don’t assume.

What’s the difference between a check valve and a non-return valve?

Same thing, different names. Some manufacturers use one term, some use the other. The symbol is identical.

Do I need a pilot-operated check or will a standard check work?

If you’re holding a vertical load or need to positively control backflow in both directions, you need pilot operation. If you just want to prevent backflow in one direction, standard is usually fine.

How do I know what cracking pressure I need?

It’s application-specific, but generally you want the minimum cracking pressure that still ensures reliable sealing. Too high wastes energy, too low causes instability. We can help you calculate this.

Can I mount a check valve in any orientation?

Most modern checks are orientation-independent, but not all. Check the manufacturer’s installation instructions, particularly for high-pressure applications.

What’s better – poppet or ball check valves?

Poppet valves generally seal better and last longer in high-pressure applications. Ball checks are simpler and cheaper but can have sealing issues at very high pressures.

How often should check valves be replaced?

Depends on the application, but in high-pressure systems we typically recommend inspection every 2-3 years and replacement every 5-7 years unless there’s evidence of problems earlier.