Menu

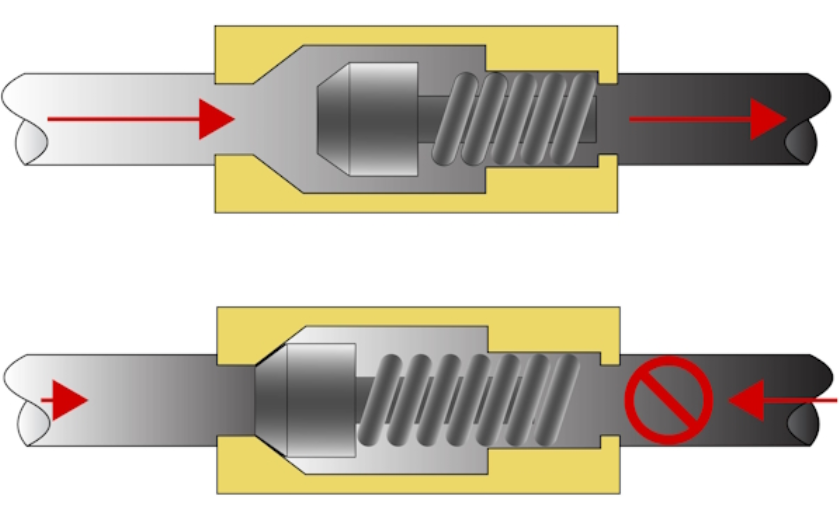

Hydraulic check valves maintain directional fluid flow despite fluctuations in temperature, pressure, and flow rates. These single direction valves use spring-loaded mechanisms and material selection to function reliably across operating ranges from -25°C to 200°C and pressures up to 6,000 psi, making them essential for systems experiencing dynamic conditions.

The foundation of a check valve’s ability to handle varying conditions lies in its material composition. Steel and stainless steel dominate hydraulic applications because they maintain structural integrity across temperature extremes while resisting pressure-induced deformation.

Steel hydraulic check valves operate effectively from -20°C to 200°C and withstand pressures up to 400 bar. The material’s thermal expansion coefficient remains predictable across this range, allowing engineers to design systems that maintain seal integrity despite temperature swings. When hydraulic systems experience rapid temperature changes—common in mobile equipment operating outdoors—steel’s consistent properties prevent valve seizure or excessive leakage.

Stainless steel variants extend the lower temperature threshold to -25°C while maintaining the same upper limit. This five-degree difference matters significantly in arctic operations or high-altitude applications where ambient temperatures plunge below standard steel’s effective range. The addition of chromium and nickel in stainless steel alloys provides this enhanced cold-weather performance while also improving corrosion resistance in marine or chemical processing environments.

The seal materials work in conjunction with the valve body. Nitrile (NBR) seals handle standard hydraulic oil across typical operating temperatures. Fluorocarbon (FKM) seals withstand higher temperatures and aggressive fluids. These elastomers compress and expand at different rates than metal components, creating a design challenge. Manufacturers address this through careful tolerance specifications that maintain sealing contact across the entire temperature range. When temperatures rise, metal expands more than the seal, potentially creating gaps. Proper design accounts for these differential expansion rates through preload calculations and seal geometry.

Cracking pressure—the minimum pressure required to open the valve—represents a critical parameter for handling pressure variations. Springs provide the closing force that establishes this threshold. In systems with substantial pressure fluctuations, spring selection determines whether the valve responds appropriately or creates operational problems.

Standard hydraulic check valves offer cracking pressures from 0.5 to 10 bar, with specialized units reaching 100 bar. The spring must be stiff enough to prevent premature opening from pressure oscillations but compliant enough to respond quickly when flow should initiate. In construction equipment that experiences sudden load changes, this balance prevents pressure spikes that could damage components. When an excavator bucket strikes an immovable object, system pressure surges. The directional check valve must remain closed to protect the pump, requiring a spring that won’t compress under these transient pressures.

Spring material selection accounts for temperature effects on spring rate. Stainless steel springs maintain consistent force across temperature ranges better than carbon steel alternatives. This consistency matters because spring rate changes with temperature—typically decreasing 0.3% per 10°C increase. In a system operating from -20°C to 150°C, this represents a potential 5% variation in cracking pressure. High-quality hydraulic check valves compensate through spring material selection and pre-compression settings that minimize this variation.

Dual-spring configurations provide redundancy in critical applications. If one spring weakens from fatigue or corrosion, the second maintains valve function. This approach appears in aerospace and safety-critical industrial systems where valve failure could have catastrophic consequences.

Hydraulic fluid viscosity changes significantly with temperature, affecting check valve performance. Standard hydraulic oil might have a viscosity index of 100, meaning its viscosity changes by a factor of two between -20°C and 100°C. This viscosity change impacts both the pressure drop across the valve and its response time.

At cold temperatures, viscous fluid requires higher pressure to flow through the valve orifice. The effective cracking pressure increases not because the spring force changed, but because viscous drag resists fluid motion. A valve rated for 1 bar cracking pressure might effectively require 1.5 bar at -20°C. System designers account for this by oversizing pumps or installing heaters for cold-start conditions.

Conversely, hot operation reduces viscosity, potentially increasing leakage past the valve seat when closed. While hydraulic non return valves are designed for zero leakage, thermal expansion and reduced fluid viscosity can allow minute bypass. In precision positioning systems, this leakage causes drift. Pilot-operated check valves address this through mechanical locking that doesn’t rely solely on spring force and seat contact.

The hydraulic nrv valve must also handle cavitation when pressure drops rapidly. As temperature increases, fluid vapor pressure rises, making cavitation more likely during quick valve closing. Manufacturers incorporate features like gradual closing mechanisms or orifice designs that avoid sharp pressure drops, protecting the valve from erosion damage that could compromise its ability to seal properly.

Real-world hydraulic systems accumulate contamination despite filtration efforts. Dirt, metal wear particles, and degraded seal material circulate through the system. Check valves are used in hydraulics to prevent backflow, but they must do so reliably even when contaminated.

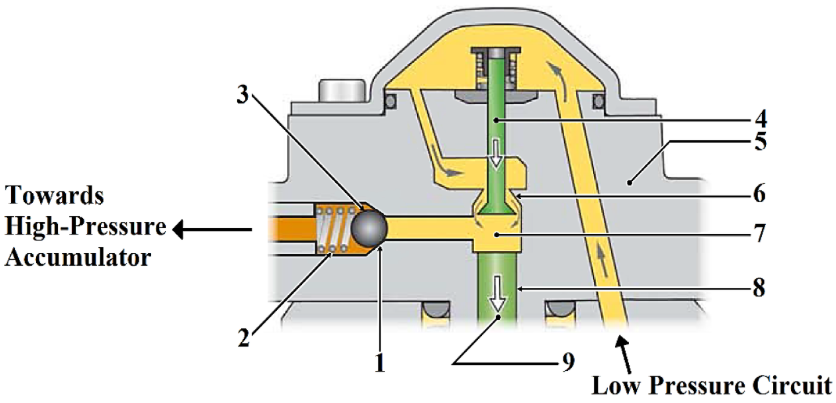

Ball-type check valves offer self-cleaning characteristics. As the ball rotates during operation, particles that might lodge between the seat and ball are dislodged. This rotation doesn’t occur uniformly, but pressure variations and flow turbulence create enough movement to prevent permanent particle embedding. This design works well for systems operating in dusty environments like construction sites or mines.

Poppet designs with conical seats provide line contact rather than the point contact of ball valves. This geometry tolerates small particles better—a 50-micron particle won’t prevent sealing on a large-diameter conical seat, whereas it might hold a ball valve open. However, poppet valves require higher flow velocities to achieve self-cleaning, making them less suitable for low-flow applications.

Spring-chamber design influences contamination tolerance. Open spring chambers allow particles to enter the spring area, potentially causing binding. Enclosed chambers protect the spring but can trap particles if contamination enters during assembly or through seal degradation. Modern hydraulic check valve symbols in system schematics now include designations for enclosed-chamber designs in critical applications.

Filter placement relative to check valves matters significantly. Installing the check valve downstream of the filter protects it from large particles. However, this position means the filter bypass valve, if activated during cold-start high-viscosity conditions, allows unfiltered fluid through the check valve. System designers balance these trade-offs based on application requirements.

Mobile hydraulic equipment experiences condition changes within seconds. An excavator digging in cold morning conditions heats up rapidly during operation. An aircraft hydraulic system transitions from -40°C at cruise altitude to 30°C on the ground within 30 minutes of landing. These rapid transitions test check valve design.

Thermal shock causes differential expansion rates between components. The valve body, machined with tight tolerances at room temperature, expands differently than internal components during rapid heating. This expansion must not cause binding that prevents valve opening or closing. Manufacturers specify clearances that remain adequate across the operating temperature range—typically 0.025mm for precision valves.

Pressure transients from sudden valve closures or pump start-up create water hammer effects. Check valves experience the full force of these pressure waves. The spring and poppet assembly must withstand repeated shock loading without fatigue failure. Testing protocols for industrial valves include millions of cycles under varying pressure and temperature conditions to verify durability.

Modern smart hydraulic systems with IoT integration monitor valve performance in real-time. Sensors track pressure drops across valves, temperature at valve bodies, and cycling frequency. This data enables predictive maintenance—replacing valves before failure rather than after. The global hydraulic valve market, valued at $8.83 billion in 2024, increasingly emphasizes these smart features as automation grows. Analysts project the market will reach $16.82 billion by 2035, with automated hydraulic valves accounting for 68.1% of market share by 2034.

Different industries demand different condition-tolerance capabilities. Understanding these requirements guides valve selection and system design.

Construction equipment operates outdoors year-round, experiencing daily temperature swings of 30°C or more. Hydraulic valves in these machines see constant pressure variations from loading and unloading operations. Manufacturers specify steel valves with wide temperature ratings and robust springs. These systems tolerate contamination better than precision industrial systems, prioritizing reliability over zero-leakage performance.

Aerospace applications demand opposite priorities. Temperature extremes are broader (-55°C to 135°C for commercial aircraft), but cleanliness requirements are stringent. Stainless steel valves with FKM seals operate in these systems, with redundant designs ensuring safety. Leakage tolerances measure in droplets per year rather than ml/min. Each valve undergoes individual testing and documentation—a practice rare in industrial applications but essential for flight safety.

Marine hydraulic systems combat corrosion while handling pressure variations from wave loading. Saltwater exposure demands stainless steel construction throughout. The pressure variations are cyclic and predictable compared to construction equipment, allowing optimized spring designs. However, the consequence of failure in marine steering or cargo handling systems is severe, requiring conservative design margins.

Industrial hydraulics in manufacturing environments operate within narrower condition ranges but demand precision. A hydraulic press requires repeatable forces, meaning check valve performance must remain consistent despite normal temperature variations from ambient changes or fluid heating during operation. These systems achieve consistency through temperature control rather than broad-tolerance valve design. Cooling systems maintain fluid within a 10°C band, allowing tighter valve specifications.

Even well-designed valves degrade over time, especially when exposed to varying conditions. Maintenance approaches differ based on application criticality and condition severity.

Scheduled replacement based on operating hours provides the simplest strategy. Construction equipment manufacturers recommend check valve inspection every 2,000 hours and replacement every 10,000 hours. This schedule assumes average operating conditions—severe conditions warrant shorter intervals. Cold-climate operations cause more seal wear from reduced elastomer flexibility. High-temperature operations accelerate spring relaxation and seal hardening.

Condition-based monitoring uses system parameters to predict valve degradation. Increased pressure drop across the valve indicates restriction from contamination or mechanical damage. Elevated system temperature might result from valve leakage causing flow recirculation. Monitoring these indicators allows intervention before complete failure.

Fluid analysis reveals valve wear. Metal particles in hydraulic fluid samples indicate surface wear on the poppet or seat. The particle size distribution helps identify the source—larger particles suggest catastrophic wear, while fine particles indicate normal operation. Automated particle counters in premium systems provide continuous monitoring, alerting operators to developing problems.

Physical inspection during scheduled maintenance intervals reveals condition directly. Technicians check spring free length to detect relaxation, measure seat concentricity, and verify seal integrity. This hands-on assessment catches problems that sensor-based monitoring might miss, particularly in systems without extensive instrumentation.

The hydraulic valve market’s 6.06% projected CAGR through 2035 is driven partly by innovations improving condition tolerance. Several technologies are emerging from research labs and early adopters.

Shape memory alloys in spring applications maintain consistent force across wider temperature ranges. These materials undergo phase transitions that compensate for thermal effects, potentially eliminating the 0.3% per 10°C variation of conventional springs. Current costs limit adoption to aerospace and military applications, but manufacturing scale-up could enable broader use.

Advanced seal materials using fluoropolymer blends extend temperature ranges while improving chemical compatibility. Some experimental formulations operate from -40°C to 230°C with minimal leakage variation. These materials also resist degradation from modern bio-based hydraulic fluids, which challenge conventional NBR seals.

Sensor-integrated valve bodies provide real-time performance data without external instrumentation. Piezoelectric pressure sensors and thermocouples embedded in the valve housing monitor conditions during operation. This data feeds into system controllers that adjust pump operation or activate cooling systems to maintain optimal conditions. While adding cost and complexity, these smart valves reduce overall system cost through improved efficiency and reduced downtime.

Additive manufacturing enables complex internal geometries impossible with conventional machining. These designs optimize flow paths to reduce turbulence and pressure drop, improving response to rapid condition changes. Topology optimization algorithms generate shapes that minimize stress concentrations, extending fatigue life under pressure cycling. Production costs currently limit this approach to aerospace and research applications, but declining printer costs will enable broader adoption.

Temperature changes affect seal flexibility, spring force, and fluid viscosity. Steel valves rated for -20°C to 200°C handle most industrial applications, while stainless steel units extend to -25°C for cold environments. Seal material selection (NBR for standard conditions, FKM for temperature extremes) determines actual operating limits. Spring force varies approximately 0.3% per 10°C change, impacting cracking pressure consistency.

Repeated pressure cycling causes spring fatigue and seat wear. Pressure spikes above design limits can deform the poppet or crack the valve body. Cavitation from rapid pressure drops erodes internal surfaces. Proper valve sizing with cracking pressure 25-30% below normal operating pressure prevents most failures. Using pilot-operated designs in high-pressure applications provides additional protection.

Yes, but with trade-offs. Stainless steel valves withstand both high pressure (up to 6,000 psi) and temperatures to 200°C. However, cost increases significantly versus standard steel units rated for 400 bar. Material thickness required for pressure resistance can limit temperature cycling performance due to increased thermal mass. Application-specific design balances these requirements rather than maximizing both parameters.

Cold temperatures increase fluid viscosity, allowing contaminants to concentrate in low-flow areas like the spring chamber. As temperature rises and viscosity drops, these particles mobilize and can wedge between sealing surfaces. Regular fluid analysis and filtration maintenance become more critical in systems experiencing wide temperature swings. Ball-type check valves tolerate contamination better than poppet designs through self-cleaning action.

Key Insights

Understanding how hydraulic check valves tolerate varying conditions requires examining material science, spring mechanics, fluid dynamics, and contamination control. Systems experiencing temperature ranges exceeding 100°C or pressure fluctuations beyond 50% of nominal require careful valve selection considering material compatibility, spring design, and seal specification. The interaction between temperature-dependent viscosity changes and valve cracking pressure affects cold-start performance and hot-operation leakage. Modern developments in smart monitoring and advanced materials are expanding operating envelopes, enabling hydraulic systems to function reliably in increasingly demanding applications from arctic mining operations to high-temperature industrial processes.