Menu

Getting hydraulic check valves certified isn’t the nightmare it used to be. Ten years ago, you’d send off drawings to a certification body and wait months for feedback. Now? Most valve manufacturers have certification pathways already mapped out for common standards like ISO 10770-1, API 6A, and CE marking under PED 2014/68/EU.

The trick is knowing which certifications actually matter for your application—and which ones are just box-checking exercises.

ISO 10770-1 certification tells you the valve passed specific tests: hydrostatic pressure testing, seat leakage verification, flow capacity measurement, and cycle endurance. That’s useful. What it doesn’t tell you is whether the valve will hold up in your specific system with your specific fluid at your specific temperature.

We had a customer spec’d a certified check valve for a mobile hydraulic system—looked great on paper, passed all the ISO tests. Failed after 8 months in the field because nobody checked whether the NBR seals could handle the bio-based hydraulic fluid. The certification was real. The application engineering wasn’t.

Cracking pressure specs matter more than most people think. Standard certification might verify 0.5 bar cracking pressure when new, but after 20,000 cycles in a contaminated system? We’ve seen that drift to 1.2 bar. Your pump’s working harder, fluid’s heating up, efficiency drops. The valve’s still “certified”—just not performing like it should.

EN 10204 material certificates come in different flavors:

2.1 certificate = manufacturer says “yeah, we used the right stuff”

3.1 certificate = manufacturer tested it and has data

3.2 certificate = third-party verified the material composition

For most industrial hydraulics, 3.1 is plenty. You’re paying 15-20% more for 3.2 certificates, which makes sense for offshore or nuclear applications but feels like overkill for a factory floor hydraulic press.

Except when it’s not overkill. We’ve tested valves from gray-market suppliers claiming “316 stainless steel”—turned out to be 304. Customer installed them in a marine application. Three months later, corrosion everywhere. Could’ve been avoided with proper material traceability.

This trips people up. Standard 316SS contains sulfur for machinability—usually 0.03% or less. But in sour gas applications (anything with H₂S), that sulfur content becomes a problem. You need 316L with <0.03% carbon AND controlled sulfur. Your material cert better specify both, or you’re guessing.

API 6A requires hydrostatic shell testing at 1.5x rated pressure. Sounds simple until the customer asks: “Can you test with our hydraulic oil instead of water?”

Here’s why that matters: water is incompressible and has different surface tension than oil. A valve that seals perfectly with water might weep oil at the same pressure because elastomer seals behave differently. We run both test media when possible—adds cost but eliminates surprises during commissioning.

The test duration varies too. Standard might call for 15-minute hold at test pressure. Nuclear applications? Try 60 minutes at pressure with helium leak detection down to 10⁻⁹ cc/sec. That’s not a typo—that’s one-billionth of a cubic centimeter per second. Space-grade seal performance.

Pressure Equipment Directive 2014/68/EU sounds intimidating but breaks down logically:

Calculate DN² × PS (nominal diameter squared times max pressure in bar)

A DN25 valve at 25 bar? That’s 625 × 25 = 15,625—you need third-party conformity assessment. Same valve at 15 bar? You’re at 9,375, still above 2500 but the category might drop depending on whether it’s Group 1 (water/steam) or Group 2 (everything else) fluid.

Most people miss the fluid classification part. Water and steam get easier treatment. Flammable hydraulic fluids? Stricter requirements kick in even at lower pressures.

ATEX certification for hydraulic valves focuses on mechanical ignition sources, not electrical. Can the valve poppet striking the seat generate enough heat to ignite surrounding atmosphere?

Testing involves dropping a weight onto the valve internals to simulate impact energy, then measuring particle temperature. Aluminum-bronze seats help because non-ferrous metals don’t spark like steel-on-steel might.

You’ll see markings like II 2 G Ex h IIC T4 Gb:

Most hydraulic systems run T4 or T5 (100°C max). If your fluid temp exceeds that under normal operation, the whole ATEX rating becomes meaningless.

A valve certified for 60 GPM at 1000 PSI might technically pass flow requirements but have awful characteristics at partial lift. We graph pressure drop vs. flow in 10% increments:

| Flow Rate | Pressure Drop |

|---|---|

| 20% (12 GPM) | 2.3 PSI |

| 40% (24 GPM) | 4.1 PSI |

| 60% (36 GPM) | 9.8 PSI |

| 80% (48 GPM) | 28.5 PSI |

| 100% (60 GPM) | 45.2 PSI |

See that jump between 60% and 80%? That’s turbulence. The valve works, it just murders your system efficiency at high flow rates. Certification passed it because the test only verified maximum flow at maximum pressure—didn’t care about the curve shape.

Cv values shift with fluid viscosity. Test a valve with ISO VG 32 oil vs. VG 68 and you’ll get different numbers. NFPA T3.21.29 methodology covers this for mobile hydraulics—same principles apply to check valves even though the standard’s written for directional valves.

ISO 9001 is baseline. You have documented procedures. Great. But:

These aren’t the same certification with different names. They require fundamentally different approaches to design review, supplier qualification, and process control.

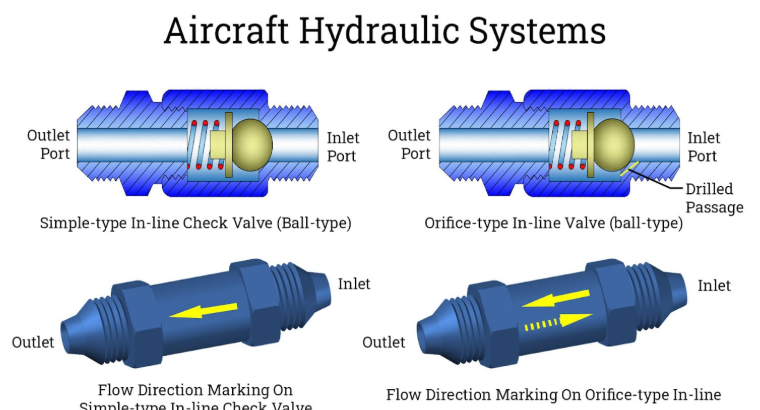

A valve manufacturer with only ISO 9001 might make perfectly good products for industrial use. But if you’re building aircraft hydraulic systems and they don’t have AS9100? You’re betting your program on their ability to scale quality without the framework that proves they can do it.

Standard certification requires 10,000 to 50,000 cycles. Your injection molding machine? That’s hitting 500,000 cycles per year. Mobile equipment sees similar numbers. The certification tells you the valve survives initial endurance testing—doesn’t tell you anything about long-term reliability.

Extended testing reveals problems:

We’ve seen seal extrusion at 200,000 cycles when certification only ran 50,000. Temperature makes it worse—NBR seals at 90°C show extrusion failure modes that don’t appear at 70°C test conditions. Spring relaxation becomes visible after 100,000+ cycles. Cracking pressure creeps upward as the return spring loses tension.

Surface galling on sliding guides? Doesn’t show up in short-duration testing. Runs fine for 50,000 cycles, then the guide surface starts breaking down and you get erratic opening behavior.

Good suppliers run extended cycle testing and have the data. If they hesitate when you ask for >100,000 cycle test results, they probably haven’t done it.

US projects reference ASME B16.34. European projects want EN 12516. Japanese systems use JIS B2001. Chinese petroleum follows GB/T standards.

These are NOT interchangeable:

ASME B16.34 Class 800 ≈ EN 12516 PN 50 (both roughly 50 bar rated)

But the pressure-temperature derating curves differ. At 200°C, ASME might allow 80% of room-temperature pressure while EN drops to 65%. Same “equivalent” rating, different performance envelope.

Multi-standard certification means multiple test programs. Add 20-30% to lead time if you need valves certified to multiple regional standards.

Nuclear applications need ASME Section III with N-stamp. That includes neutron flux exposure testing—you’re literally irradiating the materials to verify behavior under radiation. Seismic qualification requires shake-table testing to prove the valve survives earthquake conditions.

Subsea valves below 3000 meters face pressures that standard API 6A doesn’t fully address. You need finite element analysis specific to depth, material selection for hydrogen embrittlement resistance, and pressure compensation features that aren’t in catalog products.

Military aerospace requires MIL-PRF-5606 fluid compatibility (that’s the red hydraulic fluid used in aircraft), MIL-STD-810 environmental stress screening, and sometimes MIL-STD-461 for EMI. Yes, even passive hydraulic valves can generate electrical interference if they fail in ways that affect sensing circuits.

40% of warranty claims in the first 90 days trace back to installation error:

Over-torquing cracks the valve body. The certification assumed you followed torque specs. You didn’t. Valve leaks. Not a manufacturing defect—you broke it.

Wrong orientation matters on some designs. Inline check valves often need specific mounting orientation for proper drainage. Install it upside down and residual fluid stays in the valve, causing corrosion or freezing issues.

Filtration upstream needs to meet or exceed valve manufacturer’s recommendations. Certification testing used clean fluid. Your system has 100 micron contamination. Particles wedge between poppet and seat. Shutoff performance disappears.

Vibration mounting requires thought. Just because a valve’s rated for 10G shock doesn’t mean you bolt it directly to a reciprocating pump with no damping. Fatigue cracks develop at port connections.

Thread sealant matters too. Use hydraulic-compatible PTFE tape or liquid sealant rated for system pressure. Pipe dope can contaminate fluid—we’ve seen systems fail because someone used plumbing-grade sealant that broke down in hydraulic oil. Basic mistake, happens more than you’d think.

Basic poppet check valve, minimal documentation: $45-50 in volume

Same valve with full traceability, third-party testing, AS9100 QMS: $180-220

Four times the cost for what appears to be the same part. The difference? Risk transfer and documentation. The cheap valve probably works fine—until it doesn’t, and you’re explaining to a regulatory agency why an uncertified component caused system failure.

For production OEM equipment, certified valves make sense. One-off custom machinery or low-consequence applications? Maybe not worth the premium. Ask yourself: what happens if this valve leaks?

“Minor drip, wipe it up” = spend $50

“Environmental contamination, production shutdown, safety incident” = spend $200

Certification requires maintenance. API mandates periodic recertification testing. ISO standards require surveillance audits. ATEX bodies conduct random factory inspections.

Figure 10-15% of annual production needs full testing to maintain compliance:

Certification date matters. A certificate from 2019 doesn’t guarantee 2025 production meets the same standard without ongoing test records. Manufacturers who only show initial certification but can’t produce recent test data aren’t maintaining their systems properly.

Gray-market “certified” valves are a real problem. We’ve tested valves with legitimate-looking markings that failed basic pressure tests. Materials didn’t match specifications. One batch of supposed 316SS valves? Actually 304SS. Corroded rapidly in marine service.

Many certification organizations maintain online verification databases. Check the certificate number directly with the issuing body. If the supplier can’t provide a verifiable certificate number, that’s your warning.

Direct manufacturer relationships reduce counterfeit risk. Multi-tier distribution amplifies it. For critical applications, single-source procurement costs more upfront but eliminates the risk of buying counterfeit components that look right but fail when it matters.