Menu

By Marcus Wei, Industrial Systems Writer Sarah Kline, Former Equipment Editor Published: March 8, 2025

I’ve been working with hydraulic systems for about fifteen years now, and one thing that still surprises people is how much relief valves actually matter for positioning work. Most folks think of them as just safety devices – you know, something that keeps your pump from exploding when things go wrong. And yeah, that’s part of it. But there’s way more to the story, especially when you’re trying to position something accurately.

The thing is, hydraulic fluid compresses. Not a lot, but enough to mess with your positioning if you’re not careful about pressure control. I remember this one project back in 2019 where we had a vertical press that was supposed to hold position within 0.005 inches. Sounds easy, right? Wrong. Every time the load changed even slightly, we’d get this drift. Took us three days to figure out the relief valve was oscillating – barely noticeable on the gauge, but enough to cause problems.

So here’s the basic idea. You’ve got hydraulic fluid being pumped into a cylinder or motor. Pressure builds up as the load increases. The relief valve sits there monitoring that pressure, and when it hits the setpoint – say 3000 psi for argument’s sake – the valve cracks open and dumps fluid back to tank. Simple enough.

But here’s where it gets interesting for positioning work. That cracking pressure isn’t a hard wall. There’s what they call “override” – the valve doesn’t just snap open at 3000 and hold there. It gradually opens as pressure climbs above the setpoint. A cheap direct-acting valve might override 25-30% or more. So your 3000 psi setpoint actually becomes 3750-3900 psi at full flow. That’s a huge swing.

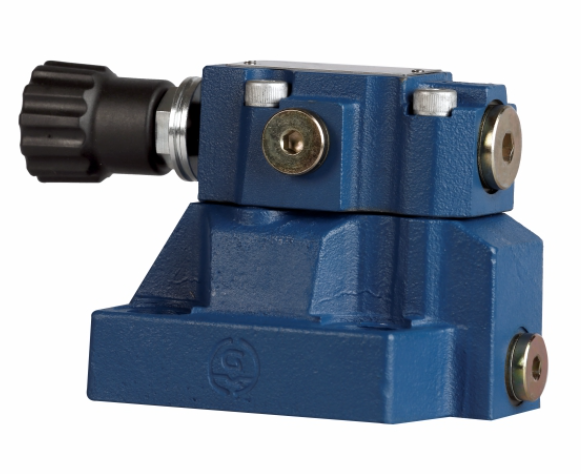

Parker and Bosch Rexroth both make decent valves, though I’ve had better luck with Parker’s stuff in high-cycle applications. Bosch tends to be cheaper but you get what you pay for sometimes. There’s also Sun Hydraulics – they specialize in cartridge valves that mount directly in manifolds, which can save a ton of space if you’re tight on room.

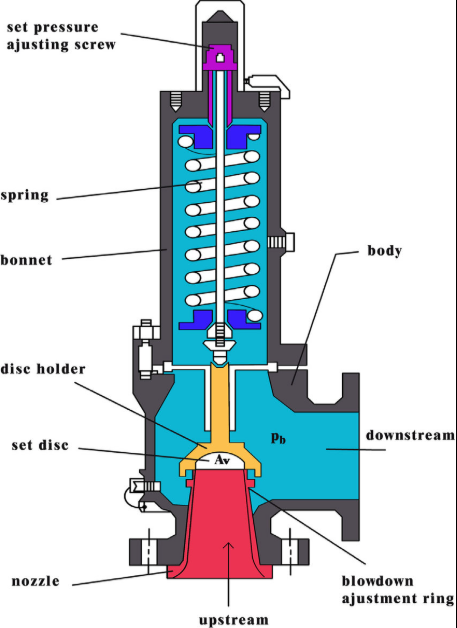

Direct-acting valves are the simpler design. Spring pushes down on a poppet or spool, system pressure pushes up. When pressure wins, fluid flows to tank. These work fine for smaller systems or where you don’t need super tight control. We use them all the time on mobile equipment – excavators, that sort of thing – where you’re more worried about not blowing hoses than holding position to a thousandth.

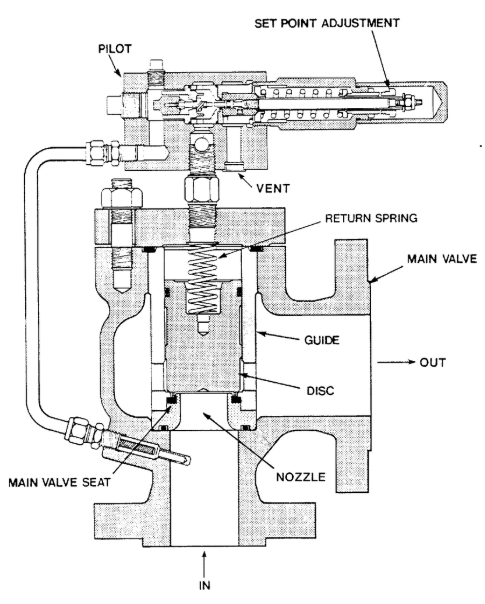

The problem with direct-acting valves is that override I mentioned. For precision work, you really want pilot-operated. These use a small pilot stage to control a much larger main stage. The pilot poppet is tiny – maybe quarter-inch diameter – so it doesn’t take much force to open it. When it opens, it bleeds off pressure from the top of the main spool, which then opens to handle the full system flow.

Pilot-operated valves typically override somewhere between 10-20%. Much better. But they cost more and they’re pickier about contamination. I learned that lesson the hard way on a machine tool application where we cheaped out on filtration. Three months in, the pilot stage was clogged and the main valve wasn’t opening properly. Had to tear down the whole valve and clean it. Not fun.

There’s also counterbalance valves, which are kind of a special case. These go in the return line of a cylinder – usually a vertical one where gravity wants to make things drop. They hold backpressure to prevent runaway, and you can adjust them to control descent speed. HydraForce makes some nice ones for mobile gear. Sun has them too. The trick with counterbalance valves is getting the setting right – too high and your cylinder won’t retract smoothly, too low and it runs away on you.

Okay so you might be wondering why we care so much about pressure override and stability. It comes down to fluid compressibility. Hydraulic oil compresses about 0.5-0.7% per 1000 psi depending on the specific fluid and temperature. Doesn’t sound like much but let’s do the math.

Say you’ve got a 4-inch bore cylinder with 10 inches of stroke. That’s about 125 cubic inches of fluid volume. At 3000 psi, the fluid compresses roughly 1.5-2% of its original volume. If pressure drops to 2700 psi because the relief valve opens and closes, you lose about 0.2% of that volume. For our cylinder, that’s 0.25 cubic inches, which translates to about 0.020 inches of position change. Not terrible for rough work, but if you’re trying to hold ±0.005, you’re already four times over budget.

This is why pilot-operated valves with lower override make such a difference in precision applications. The tighter you can hold pressure, the less position drift you get. Of course, there’s other factors too – seal friction, external loads, temperature effects. But pressure’s usually the biggest culprit.

I worked on a plastic injection molding machine once where they were having terrible shot-to-shot variation. Turned out the relief valve was set too close to normal operating pressure, so it was opening slightly on every injection cycle. Raised the setting by 200 psi and the problem mostly went away. Still had to deal with temperature sensitivity but at least we eliminated one variable.

Temperature is actually a huge pain with hydraulics in general. Fluid viscosity changes dramatically – ISO 46 hydraulic oil at 40°C has viscosity around 46 cSt, but at 100°C it drops to maybe 7-8 cSt. That’s a 6:1 change. Affects everything – flow through orifices, response time, leakage rates. Relief valves aren’t immune either. The spring force changes with temperature, though good valves use spring materials that minimize this. Still, if you’re operating from -20°C to +60°C ambient, you’re going to see some variation in cracking pressure.

Mounting location matters more than you’d think. The relief valve should be close to the pump – like within a couple feet if possible – to protect the whole system. I’ve seen installations where someone stuck the relief valve twenty feet away at the end of a half-inch line. By the time pressure waves propagate back to the valve, you’ve already had a pressure spike at the pump. Not great for pump life.

Line sizing is another common mistake. The inlet and outlet ports on a relief valve are sized for a reason. If you use undersized plumbing, you create unnecessary pressure drop, which effectively raises your system pressure. A 3000 psi relief valve with a 20 psi pressure drop in the inlet line means your pump sees 3020 psi before the valve even starts to open. Might not sound like much but it adds up, especially if you’ve got multiple restrictions in the system.

Adjustment procedure varies by manufacturer. Vickers valves typically have a hex screw with a locknut on top. You loosen the locknut, turn the screw clockwise to increase pressure, counterclockwise to decrease. Then you lock it down. Eaton uses a similar setup. Some vendors like Sun use a different arrangement where the adjustment is on the side or you need a special tool. Always check the manual.

The proper way to set a relief valve is with a load valve – basically a needle valve that lets you gradually increase pressure while monitoring with a calibrated gauge. You crack the load valve slowly until you see the gauge stop rising and hold steady – that’s your cracking pressure. Adjust the relief valve until it cracks at your desired setpoint. Sounds easy but you’d be amazed how many people just guess at it or set it by counting turns of the adjustment screw. That’s asking for trouble.

Hydraulics used to be pretty dumb – pump makes flow, valves direct it, cylinders move. Done. But that’s changed a lot in the last 10-15 years with better electronics and cheaper sensors. Now you can monitor system pressure in real time and use that data for all sorts of clever stuff.

For instance, pressure transducers are cheap now – you can get an industrial-grade 0-5000 psi transducer with 4-20mA output for under $150. Mount one near your relief valve and feed the signal to a PLC. The PLC can watch for pressure trends and alert you if things are getting close to the relief valve setting. Or it can adjust pump displacement if you’ve got a variable pump, reducing flow before you even hit the relief valve. Saves energy and reduces heat generation.

Moog and Atos both make integrated valve manifolds that combine proportional directional control, pressure relief, and sensing in one compact package. These things communicate over EtherCAT or PROFINET – industrial Ethernet protocols that are pretty common now in factory automation. Response times are fast too, like 1-2 millisecond update rates. You can do real-time closed-loop control with that kind of speed.

For positioning applications, closed-loop control typically uses encoder feedback or LVDTs to measure actual position. The controller compares actual position to commanded position and adjusts valve signals to minimize error. Standard PID control, nothing fancy. The relief valve just sits there in the background until something goes wrong. But some clever applications actually use the relief valve as part of the control strategy.

Like, imagine you’re doing a pressing operation where you need to position the ram and then apply force until you hit a target pressure. You set the relief valve to your target pressure – say 2000 psi. The positioning controller drives the ram down until it contacts the workpiece, then pressure starts building. When it hits 2000 psi, the relief valve opens and pressure plateaus there. You can hold that force as long as you want without overloading anything. Pretty slick.

If a system won’t hold position, the relief valve is one of the usual suspects. Internal leakage is common as valves age – seals wear, seats get dinged, contamination gets trapped under the poppet. Even a tiny leak, like 0.1 gallons per minute, will cause noticeable drift on vertical loads.

Easy test: isolate the cylinder with the load held, shut off the pump, and watch the pressure gauge. Should hold rock steady. If it drops slowly, you’ve got leakage somewhere. Could be the relief valve, could be a directional valve, could be cylinder seals. You have to isolate sections of the circuit to narrow it down.

Chattering is another thing you see sometimes. The valve opens and closes rapidly – dozens of times per second – making a horrible buzzing noise and causing pressure oscillations. Usually means something’s wrong. Might be the adjustment is right on the edge of the cracking point. Or contamination is holding the valve partially open. Or you’ve got cavitation in the tank line, which creates pressure fluctuations that mess with the valve.

Adding backpressure to the tank line sometimes helps with chattering. Like a 50-100 psi backpressure valve in the return line. Sounds counterintuitive – why would you want pressure in the return? – but it stabilizes the relief valve operation. You see this a lot on mobile equipment where the return line might be 15-20 feet long with multiple bends. The backpressure valve prevents the line from going into vacuum during rapid flow reversals.

Contamination is honestly the number one killer of hydraulic components. ISO cleanliness codes are a thing – they specify maximum particle counts at different size ranges. Most industrial systems target ISO 18/16/13 or better. That’s roughly equivalent to 10-micron filtration. High-performance stuff like servo valves might need ISO 16/14/11, which means 3-micron filters.

I’ve seen systems where they never changed the filters and the oil looked like chocolate milk. Pumps were worn out, valves were sticking, cylinders were leaking. Complete disaster. Fluid analysis costs maybe $40 per sample and tells you everything – particle count, viscosity, water content, additive depletion, wear metals. You should be doing it at least once a year, more often if the system runs hard.

Manufacturing is probably the biggest user of precision hydraulic positioning. CNC machine tools, injection molding, press brakes, stamping presses – all that stuff needs accurate positioning with high force. A typical injection molding machine might have clamping force of 500 tons or more, with position control to a few thousandths. Relief valves protect these systems while keeping pressure stable enough for repeatable cycles.

I did some work in a stamping plant a few years back. They had progressive dies running at 60 strokes per minute, positioning had to be within 0.003 inches or the parts came out wrong. Relief valves were set at 2800 psi with pilot-operated designs to minimize override. Worked pretty well once we got the filtration sorted out and the adjustment dialed in. Before that they were scrapping about 5% of parts due to positioning errors.

Mobile equipment is a different animal. Excavators, loaders, cranes – these machines take a beating. Shock loads, rapid direction changes, temperature extremes from -40°F to 120°F ambient. Relief valves in mobile applications typically have higher override characteristics – 20-30% is common – because you need the margin to handle transients without constantly dumping flow to tank. Danfoss and Eaton are big in the mobile market. Their valves are designed for the abuse.

Cranes are interesting because you’ve got gravitational loads that are constantly trying to make things drop. Counterbalance valves are critical there. I watched a tower crane lift one time where the load was maybe 15 tons at 150 feet of radius. The pressure in the hoist cylinders was probably 4000 psi. If the counterbalance valve failed, that load would freefall. Not good. That’s why cranes typically have redundant safety systems – mechanical brakes, backup counterbalance valves, load-sensing shutoffs.

Aerospace uses hydraulics too though it’s moving toward electric in some applications. Older aircraft like 737s or A320s have hydraulic flight controls – ailerons, elevators, rudders all moved by hydraulic actuators. These systems run at 3000 psi and have crazy reliability requirements because, you know, people die if they fail. Relief valves in aerospace applications have extensive qualification testing. They track every valve by serial number, and there’s mandatory replacement intervals regardless of condition.

The steel industry is brutal on equipment. Rolling mills generate enormous forces – thousands of tons – positioning steel to precise thickness while it’s moving at high speed. Hydraulic cylinders in these mills might be 12-inch bore or larger, running at 5000 psi. The relief valves are massive – like 2-inch ports – and they need to handle contamination because steelmaking is a dirty environment. I’ve seen relief valves the size of a small fire hydrant in steel mills.

Electronic pressure relief valves are getting more common. Traditional relief valves are pure mechanical – spring and poppet, that’s it. Electronic versions use a proportional solenoid to adjust the spring force. You can change the pressure setpoint with a voltage signal, which opens up new possibilities. Like having one valve that switches between 2000 psi for positioning and 3000 psi for clamping, depending on what the machine needs at that moment.

Bosch Rexroth has some nice proportional relief valves that integrate with their motion control systems. You can program pressure profiles – ramp up at a certain rate, hold at a target pressure, ramp down. Good for applications where shock loads are a problem.

Condition monitoring is another trend. Smart valves with built-in sensors that track cycle counts, pressure variations, temperature. This data goes to a predictive maintenance system that tells you when to replace the valve before it actually fails. Caterpillar does this on their big mining equipment. They pull data wirelessly from the machine and analyze it back at headquarters. When they see a valve starting to wear out, they schedule maintenance proactively. Saves a lot of downtime compared to reactive maintenance where you wait for something to break.

Material science keeps improving too. Seal compounds that work across wider temperature ranges, coatings that reduce friction and wear. Some valves now use diamond-like carbon coatings on the spool and bore – stuff’s incredibly hard and smooth. Expensive though. You only see it in high-end applications where the cost is justified.

Industry 4.0 is the buzzword now – everything connected to the internet, collecting data, optimizing performance. Future relief valves might report their status continuously – current pressure, adjustment position, temperature, number of times they’ve opened. Feed all that into an analytics system and you can optimize the whole hydraulic system. Maybe adjust pump pressure setpoints based on relief valve activity, or schedule preventive maintenance, or identify inefficiencies.

There’s also the push toward electrification. Electric actuators are getting better – more force dense, better speed control. But hydraulics still wins for high force in compact spaces. A hydraulic cylinder can generate 100 tons of force in a package the size of a coffee can. Try doing that with an electric linear actuator. Not happening. So hydraulics isn’t going away, but we’re seeing more hybrid systems that combine electric and hydraulic. Relief valves in these systems need to play nice with the electric control systems, which means more integration and communication.

Relief valves seem simple – just a spring and a poppet. But getting them to work right in precision positioning applications takes some thought. You need to understand the tradeoffs between direct-acting and pilot-operated designs, consider installation details like line sizing and mounting location, account for temperature effects, and integrate them properly with your control system.

I’ve been on projects where we spent weeks chasing down positioning problems, trying different valves, adjusting settings, only to find out the relief valve was fighting us the whole time. Sometimes the simplest components cause the biggest headaches.

But when everything’s set up right, relief valves do their job quietly in the background – protecting the system from overpressure while maintaining the pressure stability you need for accurate positioning. That’s really what you want from any component: does its job reliably without causing drama.

If you’re designing a hydraulic positioning system, don’t just grab whatever relief valve is cheapest or happens to be in stock. Think about what you actually need. How tight does your pressure control need to be? What are your flow requirements? What’s the operating temperature range? Is contamination a concern? Answer those questions first, then pick the valve that fits. Your future self will thank you when the system actually works right and you’re not spending late nights troubleshooting position drift.