Menu

Cedar Falls, Iowa— Years ago, a plant sought help to troubleshoot a system that had already had five pumps changed within a single week. Al Smiley, president of GPM Hydraulic Consulting in Monroe, Georgia, discovered the breather cap was missing, allowing dirty air to flow directly into the reservoir. A check of the hydraulic schematic showed a strainer in the suction line inside the tank. When Smiley’s team removed the strainer, they found a shop rag wrapped around the screen mesh. “If you change a pump, have a reason for changing it,” Smiley wrote in Machinery Lubrication. “Don’t just do it because you have a spare one in stock.”

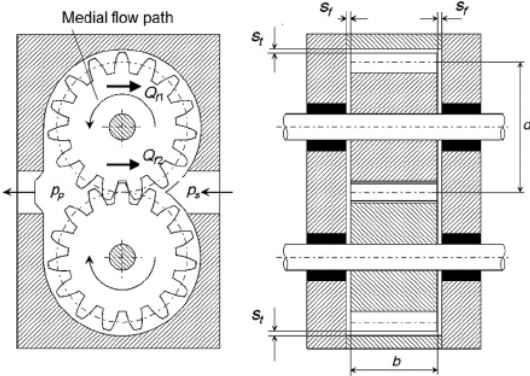

The internal gear pump is deceptively simple. An outer rotor gear drives an inner idler gear. Both turn the same direction. Fluid enters when the gears separate, travels around the casing, and exits when they mesh again. Clearances between teeth and housing run about 0.1 millimeter. Between the gear faces and housing walls, 0.025 millimeter. These tolerances matter. Mike Sondalini, who has worked in engineering and maintenance since 1974 across beverage processing, steel fabrication, and chemical manufacturing, describes what happens when they fail: dry running will tear up the housing and teeth. “Either the pump is destroyed or the fine housing clearances are lost which then allows recirculation within the pump.”

A reliability engineer at an American roofing shingle manufacturer reached out to DESMI, the Danish pump maker, looking for an alternative to filled asphalt pumps that kept failing. He had been cataloging which equipment was costing the most money. DESMI proposed their HD201 ROTAN pump. The goal: run twelve months without failure. The pump went in January 2019. A year and a half later it was still operating at original speed.

Jens Nielsen built the first internal gear pump in 1904. He was trying to drain his limestone quarry at 18th and Main streets in Cedar Falls. Water kept seeping in. In 1911 he joined with three locals—P.C. Petersen, a machinist; W.L. Hearst, a doctor; George Wyth, a shoe salesman—to form Viking Pump Company. Three were Danish. That year they made fifty pumps. Revenue: two thousand dollars. They started with two employees in space leased from a washing machine manufacturer.

Now Viking occupies 154,000 square feet of headquarters space in downtown Cedar Falls, a 320,000-square-foot machine shop, and a 78,000-square-foot foundry producing gray iron, carbon steel, 316 stainless steel, and 770 non-galling stainless steel. IDEX Corporation acquired the company in 1989.

The pumps handle viscosities from one centipoise to one million centipoise. Efficiency actually improves as viscosity increases—the opposite of centrifugal pumps. But problems emerge with thin fluids. Crane Engineering, a Wisconsin distributor, notes that low-viscosity product can slip through machined clearances from discharge back to suction. “In most cases, product slip is an annoyance and an issue for efficiency but can cause bigger problems with certain products that harden when at rest such as chocolate and adhesives.”

Thomson Process Equipment in Ireland sells Viking pumps for molasses—an important ingredient in cattle diet feeders. Molasses becomes extremely thick in cold weather. Their engineers recommend oversizing pumps and running them slowly. “If you do this, they will last for many years and pay back the extra investment in reduced power consumption, maintenance, and increased availability many times over.”

The industry has unresolved debates. Shaft sealing in asphalt applications remains difficult. Packed glands leak by design. Mechanical seals face coking—when asphalt contacts air at elevated temperatures, hard abrasive particles form. According to Fluid Engineering’s technical blog, “mechanical seal solutions on asphalt are very expensive, and usage is relatively limited to refineries and terminals owned or operated by the major oil companies.”

One forum user on Practical Machinist, trying to rebuild an old Vickers pump, got this advice from another member: “It might be rebuildable, but you’d have to take it apart and see how bad it really is. If the gears are all chewed up, then yeah, go new.”

Maintenance World recommends a simple check: pass a piece of paper between the clearances. “If it passes between the clearances easily, it indicates that the bearings have been worn down and should be replaced.”

Owens Corning in Toledo, Ohio, established 1921, manufactures shingles requiring polymer-modified asphalt. IKO, a family-run company with twenty-five plants across North America and Europe, produces its own mineral stabilizer, roofing granules, and fiberglass mat in-house. CML in Taiwan began internal gear pump production in 1987. Delta Group in India made its first pump—Model DIG-10 for low-pressure burner service—in 1968. That model is still in production.

What constitutes adequate clearance, how to prevent dry running, when to rebuild versus replace—these remain judgment calls. Sondalini suggests a flow switch in the suction line that cuts power if flow stops. Others say oversize everything. The trade-offs are not settled. “Don’t just do it because you have a spare one in stock,” Smiley repeats. But sometimes a spare is all you have.