Menu

Liquid dynamic force refers to: the additional axial force acting on the valve spool caused by oil flow within a hydraulic valve. When the flow is stable, this force is called steady-state liquid dynamic force; when the flow changes, the liquid dynamic force is called transient liquid dynamic force. For simplification, the following discussion is limited to steady-state conditions.

Liquid dynamic force should actually be examined as two types of forces.

The first is Bernoulli force. The flow generally follows the valve spool surface, with no significant change in direction. Since part of the pressure energy is converted to kinetic energy after the oil flows, as described by Bernoulli’s law, pressure is low where flow velocity is high. Therefore, the force of the oil acting on the valve spool will decrease. If we still estimate according to Pascal’s principle – “pressure is equal everywhere” – there will be deviation. The correction term added to compensate for this deviation is called Bernoulli force.

The second is impact force. The flow directly or obliquely hits the valve spool surface, and after impacting the valve spool, it changes the flow direction and velocity. The momentum undergoes a significant change, while simultaneously giving the valve spool a reaction force, which conforms to the law of momentum conservation. In most valves, the liquid flow does not directly face the valve spool surface, or the flow velocity is not high, and the momentum change is small, so the impact force is often neglected. In most hydraulic textbooks, the distinction between Bernoulli force and impact force is ignored, and they are collectively called liquid dynamic force. By artificially delineating a control volume and examining the momentum change of the control volume, as long as the control volume is properly delineated, the estimated value can also include the impact force. The liquid dynamic force mentioned below refers only to Bernoulli force.

The liquid dynamic force in slide valves and cone valves is explained separately below:

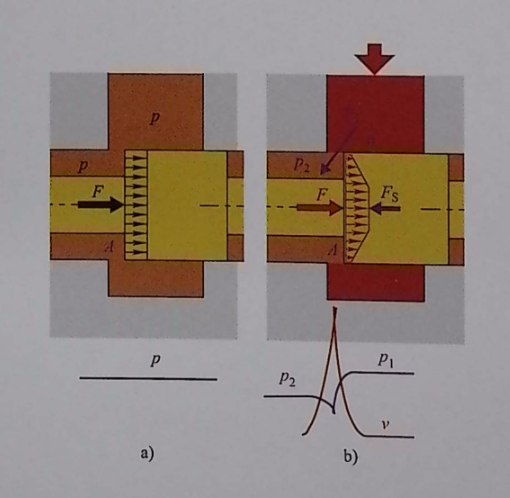

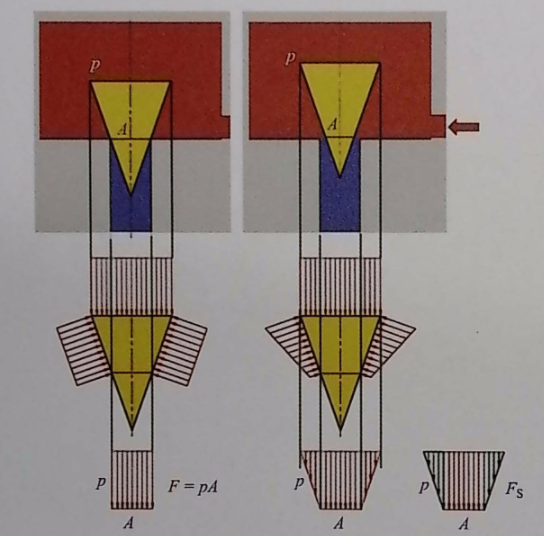

Let the annular acting area of the oil on the valve spool be A.

When there is no flow, the oil pressure in the cavity is p, and the force acting on the valve spool is F = pA.

When there is flow, near the opening, the flow passage cross-section is small, the flow velocity v is high, the pressure is low, and the actual acting force F < p₂A; at this time, a correction term F_S (which is the liquid dynamic force, it tends to close the small opening) must be added, so the actual acting force is F = p₂A – F_S.

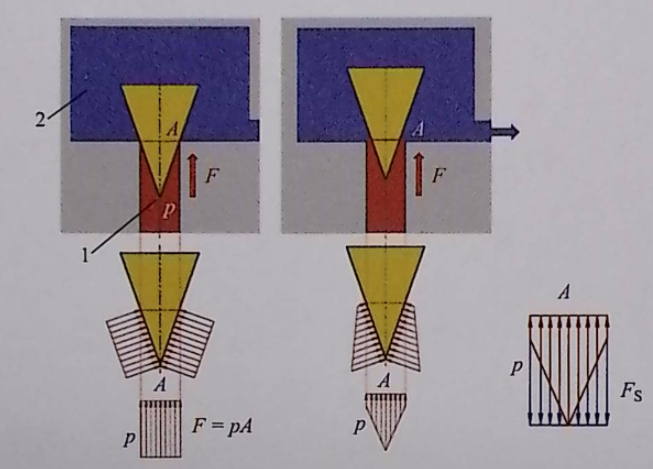

Cone valves are most commonly used in seat valves, divided into two types:

1) External flow type: liquid flows from the valve tip to the valve body

Assume that the oil pressure in the valve body area is very low, and the force acting on the valve spool can be ignored.

When there is no flow, the valve spool is subjected to equal pressure everywhere, and the axial resultant force F = pA, with no liquid dynamic force.

When there is flow, at the opening, the flow velocity is high, the pressure is low, and the axial resultant force is less than pA; a downward liquid dynamic force F_S (which tends to close the valve opening) needs to be added, so the actual acting force is F = pA – F_S.

This structure is similar to a relief valve: after opening, the force on the valve spool decreases and tends to close; but after closing the valve, the pressure rises and will push the valve spool open again. This is also one of the reasons why relief valves have large pressure regulation deviation and are prone to vibration.

2) Internal flow type: liquid flows from the valve body to the valve tip

Assume that the oil pressure in the valve tip area is very low, and the force acting on the valve spool can be ignored.

When there is no flow, the pressure distribution in the valve body area will offset part of the force, with a resultant force F = pA.

When there is flow, at the opening, the flow velocity is high, the pressure is low, the upward resultant force becomes smaller, and the total downward resultant force becomes larger; if we still calculate according to the static pressure pA, we need to add a downward liquid dynamic force F_S (which tends to close the valve opening), so the actual acting force is F = pA + F_S.

From these analyses, we can see: high flow velocity at small openings leads to low pressure, and the force on the valve spool will decrease, so the direction of liquid dynamic force always tends to close the small opening; but if the opening is closed, there is no liquid flow, and the liquid dynamic force disappears. The liquid dynamic force is like a “little troublemaker.”

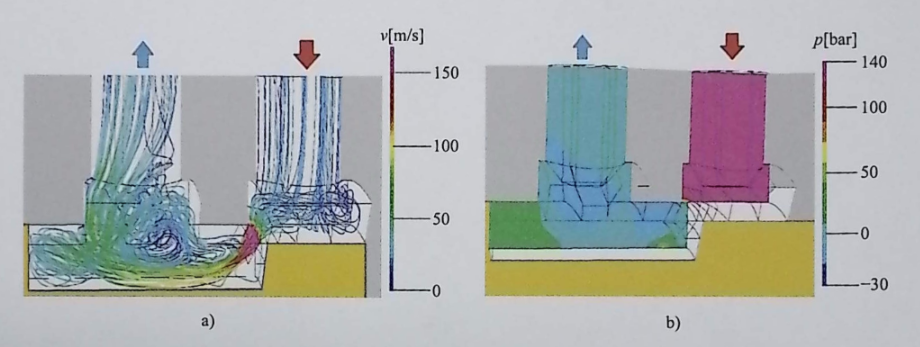

Theoretically, liquid dynamic force can be obtained through Bernoulli’s equation plus integration, but oil flow is very complex, and accurate flow velocity and pressure distribution cannot be obtained, so it is difficult to solve by integration; one can also try to use flow field simulation to calculate the force of the oil on the valve spool point by point, and obtain the liquid dynamic force after deducting the static pressure.

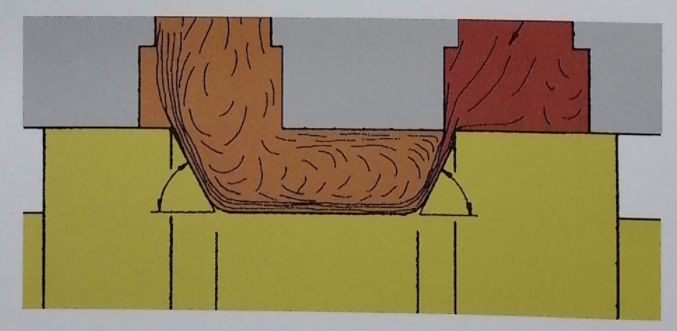

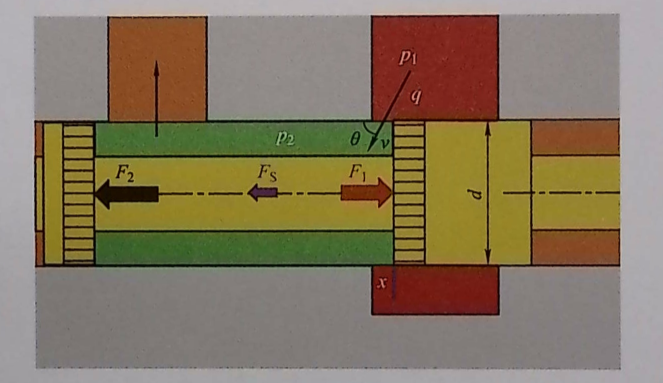

Using the method of “taking a control volume to calculate momentum change” can avoid the difficulty of finding the wall pressure distribution: for a slide valve, take a cylindrical control volume. When the oil enters the control volume, the axial component of momentum is ρqvcosθ; when flowing out of the control volume, the opening is large, the flow velocity is low, and the axial component of momentum is approximately 0. Therefore, the reaction force of the control volume on the valve is the liquid dynamic force, with the expression: F_S = ρ q v cosθ (4-1). Here ρ is the oil density, q is the flow rate, v is the flow velocity, and θ is the jet angle (it varies with the ratio of the gap between the valve body and valve spool to the opening width).

Three points need to be noted: 1) Vortex flow, cavitation, and friction near the valve opening will consume the momentum of the liquid flow, so the force calculated by the momentum method is always greater than the actually measured force. 2) The liquid dynamic force F_S is an artificially added correction term that cannot be directly measured; the force F of the oil acting on the valve spool must first be measured, and then pA subtracted to obtain the liquid dynamic force. 3) The average flow velocity v = q/A of the oil through the opening, where A is the opening area.

Substituting v = q/A into the above equation, the expression for liquid dynamic force becomes: F_S = (ρ q² cosθ)/A (4-2).

Software can be used to quantitatively understand liquid dynamic force, and “liquid dynamic pressure” (which is the liquid dynamic force divided by the valve spool end face area) can also be derived. The following are several estimation examples:

Example 1: Liquid density 860kg/m³, valve spool diameter 18mm, opening 0.25mm, opening area 14.1mm², flow rate 100L/min, jet angle 69°, flow coefficient 0.6, valve port pressure difference 16.6MPa, liquid dynamic force 61N, liquid dynamic pressure 0.24MPa;

Example 2: Liquid density 860kg/m³, valve spool diameter 18mm, opening 0.5mm, opening area 28.3mm², flow rate 100L/min, jet angle 69°, flow coefficient 0.6, valve port pressure difference 4.2MPa, liquid dynamic force 30N, liquid dynamic pressure 0.12MPa;

Example 3: Liquid density 860kg/m³, valve spool diameter 18mm, opening 0.5mm, opening area 28.3mm², flow rate 200L/min, jet angle 69°, flow coefficient 0.6, valve port pressure difference 16.6MPa, liquid dynamic force 121N, liquid dynamic pressure 0.48MPa.

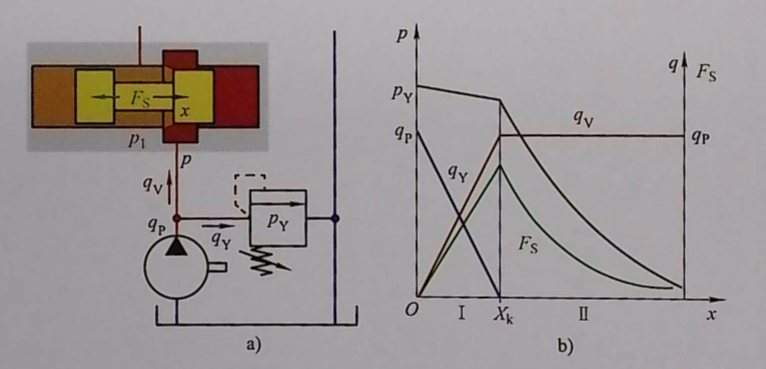

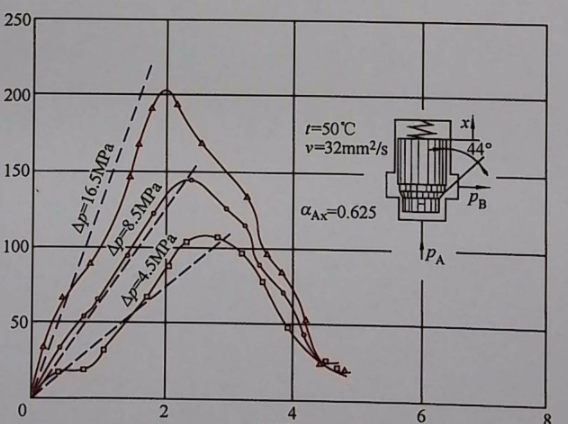

In actual hydraulic systems, the pressure difference across the opening and the flow rate passing through are not independent quantities; both change with the opening (that is, the valve spool displacement x).

The opening where liquid flow enters the valve cavity can be approximately regarded as an annular ring, with a flow area of: A = π d x (4-3).

Substituting this equation into the previous liquid dynamic force expression (4-2), we get: F_S = (ρ q² cosθ)/(π d x) (4-4). This equation shows that if the flow rate through the opening remains constant, the liquid dynamic force is inversely proportional to the displacement x.

Assuming this opening is similar to a sharp-edged orifice, the expression for flow rate is: q = C A √(2Δp/ρ) = C π d x √(2Δp/ρ) (4-5), where C is the flow coefficient.

Substituting equation (4-5) into equation (4-4), we get the liquid dynamic force: F_S = 2C² π d cosθ × Δp × x (4-6). This equation shows that if the pressure difference on both sides of the opening remains constant, the liquid dynamic force is directly proportional to the displacement x.

Actual hydraulic systems are generally simplified to consist of a fixed displacement pump, relief valve, and directional control valve, with the directional control valve spool moving to the right to open the valve port:

1) When the valve spool displacement x is relatively small, part of the flow discharged by the pump will flow out through the relief valve, and the system is approximately a constant pressure system, with the pressure difference on both sides of the opening remaining basically unchanged. At this time, the flow rate through the valve port will increase with the displacement x, and the liquid dynamic force, roughly as described by equation (4-6), is directly proportional to the displacement x and increases with x.

2) When the valve spool displacement x increases to a certain extent, all the oil discharged by the pump can pass through the directional control valve opening and no longer flows out through the relief valve. The system becomes a constant flow rate system, and the flow rate through the valve port remains basically the same as the pump flow rate. At this time, the pressure before the opening will decrease as the displacement x increases. According to equation (4-4), the liquid dynamic force is inversely proportional to the displacement x and decreases as x increases.

3) At the boundary between the two states, the pressure before the opening reaches the set pressure of the relief valve (this is the maximum pressure value), and the flow rate through the valve port also reaches its maximum. The maximum value of the liquid dynamic force is determined by this set pressure and the pump flow rate.

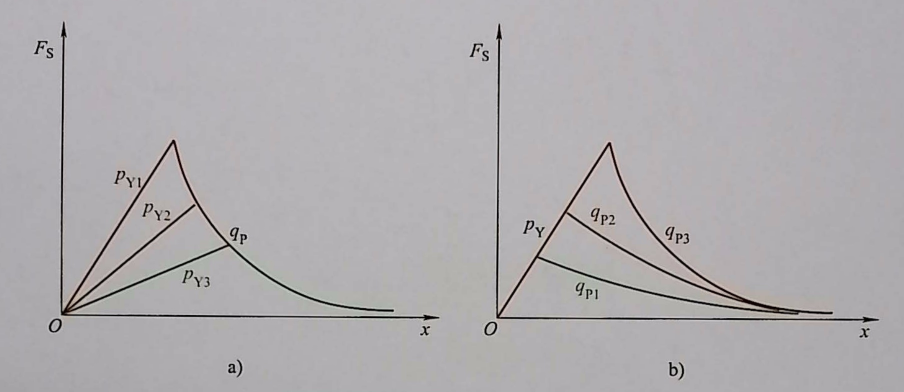

4) Liquid dynamic force under different set values:

When the flow rate discharged by the pump remains constant, because the greater the pressure difference, the greater the liquid dynamic force, when the relief valve is set to different opening pressures, the corresponding liquid dynamic force conditions are also different. The greater the set pressure, the greater the liquid dynamic force.

When the set pressure of the relief valve remains constant, because the greater the flow rate discharged by the pump, the greater the liquid dynamic force, when the pump flow rate is different, the corresponding liquid dynamic force conditions are also different. The greater the flow rate, the greater the liquid dynamic force.

This relationship of liquid dynamic force varying with valve spool displacement exists not only in slide valves but also in other types of valves. For example, research on steady-state liquid dynamic force in various different forms of slide-cone valves can also see similar changes.

Liquid dynamic force generally exists after flow through the valve port, but if the control force is relatively large, liquid dynamic force will not become a problem, and it can be ignored at this time.

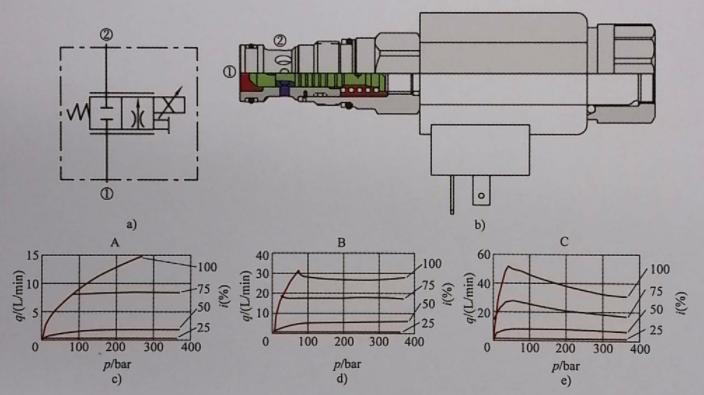

Although liquid dynamic force often plays a negative role in hindering valve spool movement, there are also examples of positive applications. For example, one type of electric proportional throttle valve cleverly uses the electromagnetic force and liquid dynamic force under different pressure differences to offset each other, so that when the valve has a small control current, it has characteristics similar to a flow control valve, that is, the flow rate does not change with the pressure difference on both sides, and the characteristics are relatively flat. However, it is not easy to achieve complete offset, so at large control currents, the characteristics of pressure difference and flow rate are still not so flat.