Menu

In summary, it is impossible to calculate the true performance of hydraulic valves by theory alone. Testing means measurement and experimentation, with emphasis on measurement. Hydraulic testing is: when a hydraulic system is actually working, or under specially set test environmental conditions, using instruments to measure the parameters of the hydraulic system, components, and their parts, thereby determining their characteristics. Although for some complex working conditions, the data obtained from testing must go through sometimes quite complex analysis and processing, only testing can capture the true performance of hydraulic valves.

Hydraulic technology was established and developed on the basis of testing. The following are a few examples.

As mentioned earlier, the pressure difference across the opening determines the flow through the opening. The flow regime of the oil (turbulent/laminar) has an extremely large impact on the flow rate: under the same pressure difference, the flow calculated by turbulent and laminar formulas often differs by several times. The dividing line determining flow regime, the “Reynolds number,” was determined by Reynolds in 1883 through tens of thousands of experiments:

These values are not theoretical calculations but obtained through testing.

The “Reynolds number – resistance coefficient diagram” currently in university textbooks was fitted by Nikuradse and others based on extensive experiments.

The thin-walled orifice pressure difference-flow formula widely used in hydraulics has many prerequisites. Details can significantly affect the flow coefficient: differences in orifice details alone can change the flow coefficient from 0.7 to 2. These are only known through testing.

In some textbooks, hydraulic valve opening flow often applies the thin-walled orifice formula, but this formula is not accurate even for standard thin-walled circular orifices, and is even less suitable for valve openings with complex shapes. It must be confirmed through testing.

Domestic university hydraulic textbooks mostly copy the theoretical formula of “calculating flow forces from momentum changes,” but Professor Lu Yongxiang’s research at RWTH Aachen University in Germany showed: theoretically calculated flow forces are greater than test values and do not reflect the trend of “flow forces decreasing as valve spool stroke increases.” He pointed out: testing methods are closer to engineering reality and can obtain steady-state flow force curves that contain complex internal factors, but this viewpoint has not been taken seriously by some domestic professors to this day.

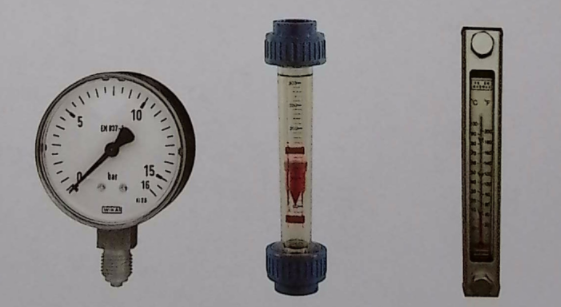

Pipeline flow can be roughly estimated at open outlets, but cannot be judged in closed steel pipes; pressure was even more difficult to estimate before the invention of the pressure gauge in 1849, which once led to steam engine boiler accidents. The development of hydraulic technology depends on testing instruments: modern hydraulic testing instruments have accuracy mostly between 2% and 0.1%, with credibility far higher than theoretical calculations. Hydraulic testing instruments are divided into two categories: direct display type and recording type.

Generally have no recording capability, such as pressure gauges, float-type flowmeters, and oil thermometers.

Advantages: direct reading, intuitive, no intermediate links, low cost.

Disadvantages:

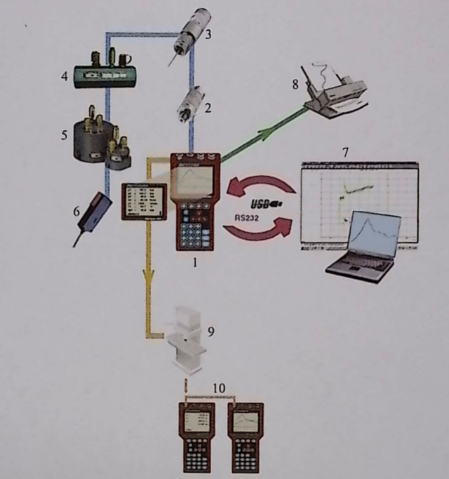

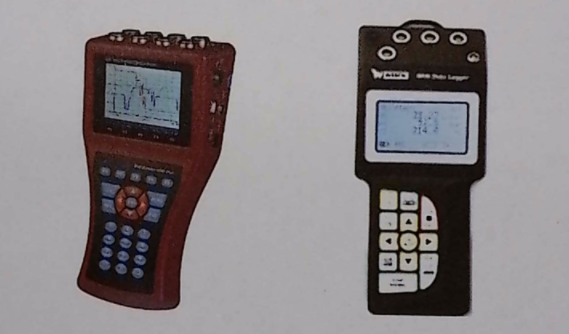

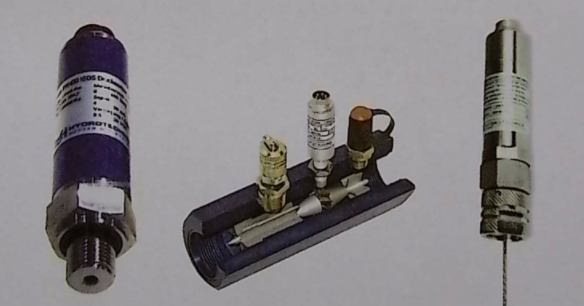

Appeared sixty to seventy years ago (initially analog type), evolved to digital type 40 years ago, with prices dropping significantly; at the same time, “portable data acquisition instruments” appeared, which can connect pressure/flow/temperature sensors and are called “hydraulic multimeters.”

Measured quantities are converted to electrical signals through sensors and can be recorded, processed, displayed, an d transmitted.

d transmitted.

Advantages: