Menu

Here’s the thing about pressure relief valve hydraulic systems – they’re basically the emergency exit for your hydraulic setup. When pressure gets too high (and it will), these valves crack open and dump fluid back to tank. Simple as that.

You’ve got hydraulic systems running everywhere these days. Manufacturing plants, construction sites, farms, mining operations. They all need these valves because hydraulic pressure doesn’t mess around. I’ve seen what happens when a relief valve fails on a 3000 PSI system. It’s not pretty. Hoses explode like grenades, oil sprays everywhere, and you’re looking at thousands in damage plus however long it takes to get back online.

The valve’s job is straightforward – sit there doing nothing until pressure hits the set point, then open up. Once pressure drops back down, close again. Repeat for the next 10 years.

Walk into any automotive stamping plant and you’ll see hydraulic presses everywhere. Big ones, small ones, some running 24/7. Each one needs a relief valve because press tonnage creates massive pressure spikes.

We’re talking hundreds of cycles per hour. The valve opens, closes, opens, closes – all day long. A buddy of mine works maintenance at a GM supplier plant. They’ve got maybe 40 presses on the floor. He says they replace or rebuild relief valves every 18-24 months on the high-cycle equipment. The ones that run lighter duty? Those go 5 years easy, sometimes longer.

Textile operations are different but they still beat up hydraulics. Fabric cutting machines, industrial presses for bonding materials, conveyor systems moving rolls of cloth that weigh 500 pounds each. The problem in textile isn’t so much the pressure cycles as the contamination. Lint gets into everything. I mean EVERYTHING. You’ve got to use sealed valves or you’re rebuilding them constantly because fibers jam up the poppet.

There’s a plant in South Carolina – won’t name names – but they were having relief valves fail every few months on their material handling system. Kept replacing them with cheap Chinese knockoffs to save money. Finally brought in a hydraulics guy who told them the valves were fine, they just needed better filtration on the system. $3,000 in filters saved them probably $15k a year in valve replacements and downtime.

Every excavator, loader, dozer, crane – they’re all hydraulic. No way around it. And contractors don’t baby their equipment. They push it hard because time is money on a job site.

Relief valves on mobile equipment take a beating. You’ve got temperature swings – machine sits overnight in 20-degree weather, then the operator fires it up and starts digging without letting it warm up properly. Cold oil, high pressure, shock loads from hitting rocks or tree roots. The valve’s working constantly.

Cat, Komatsu, Deere – they all spec their relief valves pretty conservatively because they know how their equipment gets used. Or abused, really. I’ve watched operators on trackhoes jamming the bucket into clay so hard you can hear the relief valve screaming from 50 feet away. That’s just normal operation in construction.

The worst is when you get a new operator who doesn’t understand hydraulics. They think if they push harder the machine will dig faster. All they’re doing is cycling the relief valve unnecessarily and making heat. Seen plenty of excavators overheat because the operator kept the valve pegged open all afternoon.

Tractors, combines, sprayers – modern farm equipment is basically rolling hydraulic systems. Some of these machines have 6 or 8 separate hydraulic circuits running at the same time.

Farming is brutal on equipment. Dust is everywhere during harvest. You’re running long hours – 16, 18 hour days when the weather’s good and crops are ready. Can’t stop for maintenance when you’ve got 500 acres of soybeans that need combining before the rain hits.

Relief valves on farm equipment need to last because nobody wants to fix them in the middle of harvest. Had a farmer tell me once his combine relief valve started weeping during wheat harvest. He knew it was getting worse but he gambled on finishing the field. Made it through wheat, barely. Then it let go completely three days into soybeans. Lost probably two days waiting for parts, plus the valve, plus labor. Would’ve been cheaper to stop and fix it right away but that’s not how farming works when you’re racing weather.

The other issue on farms is service intervals. Industrial equipment might get serviced every 250 hours. Farm tractors? Maybe once a year, if that. The relief valves just have to keep working through mud, dust, temperature swings from -10 to 100 degrees, and general neglect. Which most of them do, honestly. Modern ag equipment valves are pretty robust.

Small hydraulic jacks run at maybe 2000 PSI. Bottle jacks, floor jacks, that kind of thing. Light duty.

Industrial presses? Different story. Metal forming operations hit 5000, 8000, even 10,000+ PSI. The relief valve has to be rated for this. Seems obvious but you’d be surprised how many people mess it up.

Underrate the valve and it opens all the time. You’re just dumping fluid back to tank constantly, making heat, wasting power. Machine runs like garbage.

Overrate it and the valve doesn’t open when it should. Now you’re relying on something else to fail first – usually a hose or seal. Those cost more to replace than just getting the right valve in the first place.

Pressure rating is one thing. Flow capacity is another. You can have a valve rated for the right pressure but if it can’t flow enough GPM, pressure keeps building even with the valve wide open.

This happens more than you’d think. Somebody sizes a relief valve for a small pump, then later they upgrade to a bigger pump for more speed. Forgot to check if the relief valve can handle the extra flow. Now you’ve got problems.

Standard industrial valves might flow 10-30 GPM. Big ones go 50, 75, 100+ GPM. Mobile equipment usually needs less flow but faster response. It’s a trade-off.

Most industrial valves are steel or cast iron. Works fine for standard petroleum-based hydraulic oil in a factory environment.

Marine stuff? Whole different ball game. Salt water eats steel for breakfast. You need stainless or bronze or some kind of corrosion-resistant alloy. Costs 3-4 times as much but there’s no choice.

Food processing has its own requirements. FDA-compliant materials, special finishes on any wetted surfaces. Can’t have standard steel because it’ll rust and contaminate product.

Then there’s the seals. Most valves use Buna-N (nitrile rubber) for seals and O-rings. Works great with petroleum oils. But if you’re running fire-resistant fluids like phosphate esters – common in aerospace, foundries, places where fire risk is high – Buna-N dissolves. You need Viton or EPDM. Nobody tells you this until you’ve already had a seal failure.

Guy I know runs maintenance at a die casting plant. They use fire-resistant fluid because they’re working around molten metal. Bought a batch of relief valves online, cheap. All had Buna-N seals. Every single valve failed within 3 months. $5000 lesson in seal compatibility.

Mobile equipment typically needs fast-acting valves. Pressure spikes happen quick when you’re slamming a bucket into hard ground. The valve needs to crack open in milliseconds.

Stationary industrial equipment doesn’t usually need that. Pressure builds slower. A standard response valve works fine and costs less.

Where people screw up is mixing applications. Put a slow industrial valve on mobile equipment and you get pressure spikes before the valve can react. Put a fast mobile valve on a smooth industrial system and it opens too easily, cycles constantly, makes noise.

Grain elevator in Iowa – I think it was near Des Moines but might’ve been further west – anyway, they had a hydraulic conveyor system moving grain. Relief valves were rated for the correct pressure, 2500 PSI or whatever it was. Problem was the valves couldn’t flow enough GPM.

Harvest season hits, they’re running full bore, and the valves open but can’t dump pressure fast enough. System pressure climbs anyway. Blew out three hydraulic hoses in two days. Made a huge mess. Hydraulic oil all over the grain – had to throw out probably 1000 bushels of contaminated product. Then they’re down for three days during peak season waiting for hoses and cleaning up.

All because somebody saved $200 buying smaller relief valves. Probably cost them $30,000 when it was all said and done.

On the flip side, there’s a construction outfit that made the opposite mistake. They maintained a mixed fleet – big excavators, compact excavators, skid steers. To simplify parts inventory, they bought one high-flow relief valve model that would “work on everything.”

Worked fine on the big machines. But the compact excavators were bypassing constantly. Valves opened too easy. Machines lost power, ran hot, fuel economy went to hell. Operators were complaining the machines felt sluggish.

Took them a whole season to figure out the problem. Soon as they put properly-sized valves back on the compact equipment, everything ran normal again. Another expensive lesson in “one size fits all doesn’t work with hydraulics.”

Mining operations are probably the hardest on relief valves. Underground equipment, confined spaces, no ventilation, heat buildup is a nightmare. These valves are doing double duty – protecting from overpressure AND trying not to generate excess heat while they’re at it.

Some mines spec low-heat-rise valve designs. Cost more – sometimes double – but in a confined underground heading where it’s already 90 degrees and humid, reducing heat generation is worth the premium. Seen mines where they didn’t use proper valves and had to shut down sections because it got too hot for the crew to work safely.

Factory-set valves come locked at a specific pressure. Can’t adjust them without special tools or breaking the seal. OEMs like these because they know exactly what pressure the system needs and they don’t want field techs messing with it.

Adjustable valves have a screw you turn to change the pressure setting. More flexible but also more ways to screw it up.

Set it too high? Defeats the whole purpose of having a safety valve. Set it too low? You’re dumping pressure constantly and the system doesn’t work right.

I’ve walked into shops where every relief valve was set randomly because different technicians adjusted them over the years with no documentation. Nobody knew what the correct settings were supposed to be. Had to re-baseline everything from scratch.

Only real way to know if a relief valve works is testing it under load. Bench testing tells you if the valve opens at the right pressure with clean oil at 70 degrees. That’s about it.

Install testing shows you what happens with real system conditions – hot oil, contamination, actual flow rates, dynamic loads.

Aviation has mandatory testing schedules. Those hydraulic systems get inspected constantly. Construction equipment? Maybe it gets tested when somebody remembers to. Or when it fails.

Most people rely on “it’s working until it isn’t” method of testing. Which works until it doesn’t.

Wear on the seat and poppet is the most common failure mode. Valve opens and closes thousands or millions of times, metal wears, eventually it starts leaking even when pressure is normal.

Contamination jams things up. Dirt gets past the filters (or there are no filters), wedges in the valve, now it’s stuck open or stuck closed. Stuck open means no pressure control. Stuck closed means something else fails – usually catastrophically.

Wrong adjustment is technically operator error but I’m including it here because I see it constantly. Valve opens too soon or not soon enough because somebody set it wrong.

External leaks are usually seals. Easy fix, costs maybe $20 in parts and an hour of labor.

Internal leaks across the seat mean you need to rebuild or replace the valve. Most valves can be rebuilt 3, 4, maybe 5 times before the body wears out and you just need a new one.

Purchase price is just the start. Basic industrial relief valve might be $150. Pilot-operated valve for higher flow? $800. Specialized marine-grade stainless? $1500+.

Then you’ve got installation labor. If you’re just swapping an existing valve, maybe 2 hours. If you’re adding one to a system that doesn’t have it, could be a full day running new plumbing.

Testing and commissioning adds cost. Some places require pressure testing, flow testing, documentation. That’s not free.

For critical equipment, lots of companies keep spare valves on the shelf. Downtime costs more than the valve. Manufacturing plant loses $10,000 an hour when the line is down? Yeah, they’ll spend $2000 keeping spares around.

Maintenance costs are all over the map. Simple direct-acting valves? Might go years with zero attention beyond looking at them occasionally. Complex pilot-operated valves need regular service, somebody who knows what they’re doing to rebuild them, and more expensive parts.

What’s funny is how different industries calculate value. Manufacturing plant will pay premium for reliability because production downtime kills them. Rental equipment company buys cheap and plans to replace because their machines don’t run as hard and customers beat them up anyway. Different business models, different math.

Old hydraulic systems were dead simple. Lever, pump, cylinder, relief valve. All mechanical. Worked forever, easy to fix.

Now everything’s got electronics. Pressure sensors, flow meters, PLCs controlling everything. Some relief valves have built-in pressure transducers so you can monitor them remotely.

Maintenance departments love this when it works. They can see how often the valve opens, what pressures it’s seeing, spot trends before failures happen. Data logging and predictive maintenance and all that.

When it doesn’t work? Now you’re troubleshooting electronics on top of hydraulics. Need a technician who understands both. Those don’t grow on trees.

IoT stuff is creeping into hydraulics too. Connected valves sending data to the cloud. Fleet managers monitoring equipment across multiple sites from their desk. Sounds great in the sales pitch.

Reality is most shops don’t have the IT infrastructure or the people to actually use all this data. They’ve got connectivity issues, subscription fees for the monitoring platform, and technicians who don’t trust the sensors anyway because they’ve seen enough of them fail.

That said, when companies actually implement it properly, the results are real. Caught developing problems early, scheduled maintenance before breakdowns, reduced downtime. Just costs money and effort to do it right.

Depends entirely on the application. Mobile construction equipment might last 5-7 years before it’s worn out or obsolete. The relief valve probably gets replaced 2-3 times in that span, maybe more if the machine works hard.

Industrial hydraulic presses in a factory? Some of those run 30, 40 years. Relief valve might last 10 years, might last 20, depends on cycles and maintenance.

Some manufacturers offer extended warranties. 5 years, sometimes longer for critical applications. Warranty itself doesn’t mean much – it’s more about what it signals. Company willing to warranty a valve for 5 years probably did the engineering to make sure it’ll last that long.

Environment makes a huge difference. Indoor factory equipment in climate-controlled conditions? Valve will last forever compared to one on a farm tractor that sits outside year-round seeing -20 in winter and 100 in summer.

Marine applications eat valves faster because of corrosion. Even with stainless or bronze, salt water finds a way. Maintenance schedules are tighter, replacement cycles are shorter.

Honestly, in most cases the valve outlasts the equipment it’s on. Or the equipment gets upgraded and the valve gets replaced as part of the upgrade even though it was still working fine.

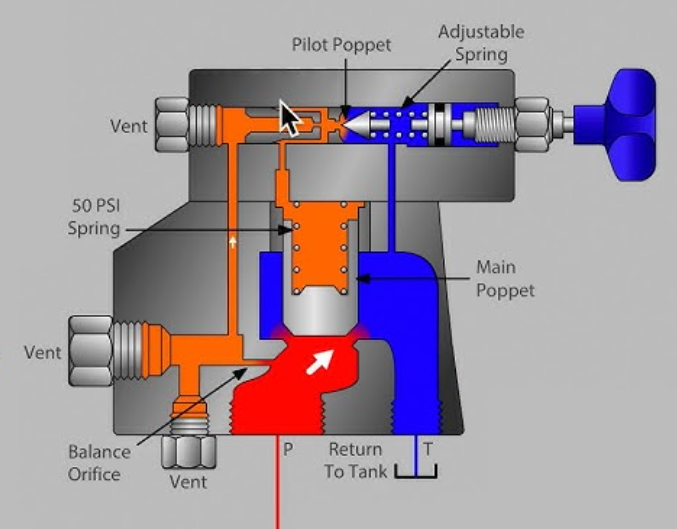

Basic principle: spring pushes poppet against seat. System pressure pushes back. When pressure force beats spring force, poppet moves and opens a path for fluid to dump back to tank. Pressure drops, spring wins again, poppet closes.

That’s it for simple direct-acting relief valves. Works fine for lower flow applications.

Reality gets messier. Fluid dynamics, temperature effects, dynamic loads all affect how the valve behaves. High-pressure systems need damping or the valve chatters – opens and closes rapidly making noise and wearing out fast. High-flow applications need big passages or the pressure drop through the valve becomes an issue.

Pilot-operated valves are more complex. Small pilot valve controls a bigger main valve. Lets you get precise pressure control without needing a massive spring. These handle higher flows more efficiently than direct-acting valves but cost more and need cleaner fluid. Contamination causes problems faster on pilot-operated designs.

Most industrial applications use direct-acting because they’re simpler and more forgiving. Mobile equipment often uses pilot-operated because they need higher flow capacity in a smaller package.

Operating hydraulic equipment doesn’t require much knowledge about relief valves. Push the lever, stuff moves. That’s enough for most operators.

Maintenance techs need to actually understand how this stuff works. Hydraulic theory, valve operation, troubleshooting. Problem is finding techs who know hydraulics anymore.

Trade schools and community colleges offer programs but enrollment is down. Equipment manufacturers do training on their products but that’s brand-specific. Industry groups like the National Fluid Power Association have certification programs but not many people pursue them.

The real knowledge gap is generational. Old-timers who’ve been working on hydraulics for 30 years are retiring. Younger techs coming in have strong electronics and computer skills – they’re great with PLCs and sensors and diagnostics software. But they’ve never actually plumbed a hydraulic system or rebuilt a relief valve or understood why flow and pressure behave the way they do.

Seen plenty of situations where a machine problem gets blamed on “bad hydraulics” when the real issue is electrical or mechanical and the hydraulic system is working exactly like it’s supposed to. But the diagnostic process stops at “hydraulic problem” because that’s the tech’s weak area.

This affects relief valve maintenance across all industries. Valves get set wrong, rebuilt incorrectly, or replaced unnecessarily because nobody really understands them anymore.

Relief valves look simple but supply chain can be a mess. Standard industrial valves? Most distributors stock them, ship same day or next day. No problem.

Specialized stuff for unique applications? Could be 8, 10, 12 weeks lead time. Maybe longer if it’s custom or low-volume.

Older equipment is a nightmare for parts. Valve manufacturer went out of business 20 years ago. Original equipment manufacturer doesn’t support that model anymore. You’re stuck cross-referencing specs trying to find a modern equivalent that’ll fit the mounting and work with the system pressure and flow.

Sometimes you get lucky and find a direct replacement. Other times you’re modifying brackets or replumbing because the new valve is a different size or has different port locations.

Supply disruptions the last few years really highlighted how fragile some of these supply chains are. Companies that ran lean and ordered parts just-in-time got burned when lead times stretched from 2 weeks to 6 months.

US industrial hydraulics follow NFPA and ANSI standards mostly. Design requirements, testing procedures, performance specs. But here’s the thing – they’re not legally required for most applications. They’re more like guidelines. Companies follow them because insurance or customers require it, or because it’s good practice.

Europe has ISO standards that are similar but different enough to be annoying if you’re selling equipment internationally. Need valves that meet both? Adds cost and complexity.

Aviation is strict. FAA specs for everything. Mining has MSHA breathing down your neck. Mobile equipment increasingly deals with EPA emissions rules which affects how hydraulic systems get designed, including valve selection.

Insurance companies add their own requirements sometimes. Factory’s liability insurer might require specific relief valve testing intervals or certain safety factors in pressure ratings. Don’t comply and your coverage gets voided.

Honestly most smaller operations don’t worry about standards much unless they’re selling to big companies or government that require compliance documentation.

Electronic pressure relief is a thing now. Instead of a mechanical spring and poppet, you’ve got an electronic valve controlled by a pressure sensor. Precise pressure control, remote adjustment, integrates with control systems.

Sounds great until you factor in cost (3-4x mechanical valves), complexity, and electrical power requirements. Plus now you’ve got electronics that can fail in ways mechanical valves don’t.

Some applications justify it. Most don’t. We’ll see if costs come down enough to make them mainstream.

3D printing is supposedly going to revolutionize valve manufacturing. Complex internal geometries that improve flow, custom designs, all that. Few companies experimenting with it. Not seeing much real adoption yet beyond prototypes and specialty applications.

Condition monitoring technology exists and works. Sensors detect performance degradation before catastrophic failure. Saves money, prevents downtime. Problem is it costs money up front and most operations don’t want to spend on prevention when “if it ain’t broke don’t fix it” has worked fine for years.

Critical applications – aerospace, mining, offshore drilling – they’re adopting this stuff. General industrial? Agricultural? Construction? Not so much, except for the big operators with serious maintenance programs.

Match the valve specs to your system requirements. Operating pressure, flow rate, fluid type, environment, expected service life. It’s not complicated but people still screw it up.

Don’t cheap out. The valve that costs $100 less but has marginal specs will cost you way more when it fails early or doesn’t protect your equipment properly.

Don’t overbuy either. Fanciest most expensive valve isn’t automatically the best choice. Sometimes you’re paying for features you’ll never use.

Work with distributors or manufacturers who actually know their stuff. Guy who’s seen a thousand hydraulic applications can usually recommend something based on real-world experience not just catalog specs.

The right valve for your application might not be what you think it is. That’s fine. Better to figure it out before installation than after you’ve got problems.