Menu

Since the late 19th century, when the rapid development of electrical engineering brought enormous changes to industry and society, hydraulic engineering technicians have consistently hoped to control hydraulic valves through electrical means.

Switching electromagnets appeared in the early 20th century and could achieve electrical control, but they could only be on or off and could not finely regulate the displacement (stroke) of the hydraulic valve spool, and thus the opening.

Because magnetic field strength is proportional to the current passing through the coil, the force generated by the armature-sleeve assembly is proportional to the current. Therefore, by controlling the current, the force acting on the valve spool can theoretically be controlled.

The problem is that the electromagnetic force output by ordinary electromagnets also severely depends on the air gap — it is inversely proportional to the air gap. The air gap is determined by the armature stroke, so as the armature stroke (valve spool displacement) changes, the air gap changes, and the electromagnetic force also changes accordingly, making it very difficult to control the valve spool displacement.

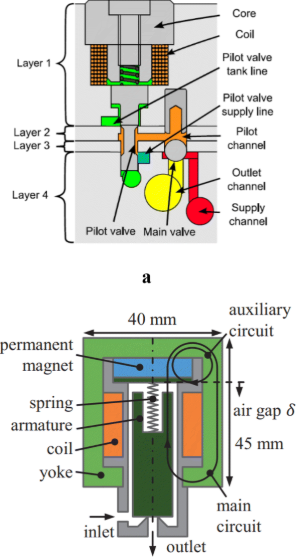

In the 1940s, classic servo valves were invented, such as nozzle-flapper servo valves, which could control valve spool displacement. Although they had good performance, their structure was sophisticated and complex, manufacturing costs were very high, which was unfavorable for the widespread application and development of electrical control in hydraulic systems.

In the 1970s, electromagnets were invented whose output force (electromagnetic force) could remain essentially unchanged with armature stroke — proportional electromagnets. Their structure was much simpler than classic servo valves, and manufacturing costs were also much lower. Therefore, they quickly gained widespread application, bringing breakthrough progress to electrical control of hydraulic systems.

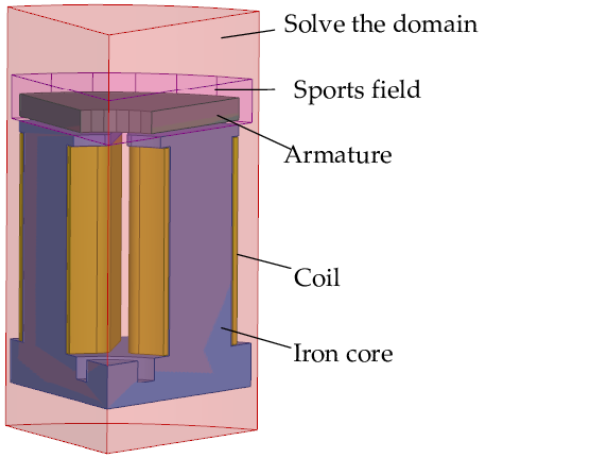

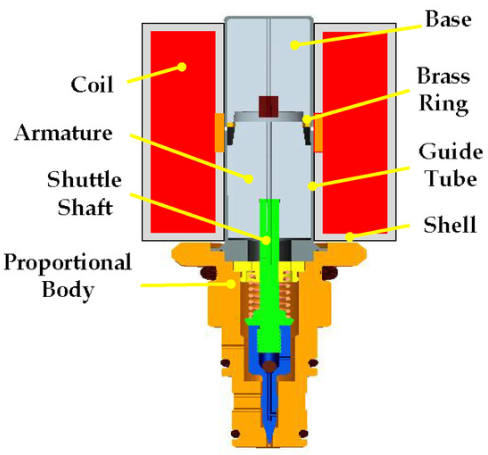

Similar to switching electromagnets, proportional electromagnets also consist of coils, armature-sleeve assemblies, and other components.

The coils used for proportional electromagnets can be the same as those used for switching electromagnets; some suppliers’ coils are interchangeable. The composition of the armature-sleeve is also roughly similar to that of switching electromagnets.

The armature-sleeve assembly used for pressure valves differs from that for flow valves.

The displacement of the pressure valve spool varies with flow rate; the key to controlling pressure is controlling the force acting on the valve spool.

Ordinary non-electrically controlled relief valves control the force acting on the valve spool through a spring. Electrical control means using a proportional electromagnet to replace the spring, controlling the force acting on the valve spool through the push rod by controlling the current, thereby controlling the opening pressure.

Relief valves inherently require small valve spool displacement. If the valve spool displacement is limited to a very small range, the corresponding air gap change is small, and the effect on the electromagnetic force is minimal, so the armature-sleeve assembly does not require any special design.

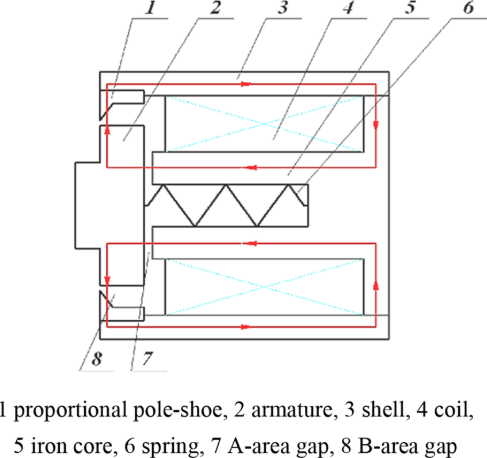

In the armature-sleeve assembly used for electro-proportional relief valves, stainless steel with medium magnetic permeability is used as the sleeve. Axially, because the cross-sectional area of the sleeve is very small, very few magnetic field lines pass through. Radially, due to the large area, the vast majority of magnetic field lines can pass through. A closed magnetic circuit is formed through the armature and pole piece, generating electromagnetic force, which is transmitted to the valve spool through the push rod. In this way, by controlling the current, the set pressure can be controlled.

For example, Haydlx’s non-electrically controlled direct-acting relief valve RV08-20 can handle flow rates up to 22L/min, while the company’s electro-proportional direct-acting relief valve TS08-20 of the same size has a working flow rate of only 4L/min, precisely due to this limitation — the valve spool displacement is less than half.

For proportional electromagnets to be used in flow valves such as throttle valves and directional throttle valves, two problems need to be solved: first, how to make the output electromagnetic force essentially unaffected when the valve spool displacement (air gap change) is much larger; second, electromagnets can only control electromagnetic force, so how to control displacement. The proportional electromagnets mentioned below mainly refer to this type.

The position and shape of the magnetic isolation ring are arranged so that the armature and sleeve partially overlap radially. This allows part of the magnetic field lines to pass radially through the sleeve in the overlapping area, closing the magnetic circuit.

In this way, as the armature displaces, the overlapping part between the armature and pole piece becomes increasingly larger, more and more magnetic field lines pass radially through the sleeve, and fewer and fewer magnetic field lines pass axially through the air gap from the armature end face. Therefore, although the axial magnetic resistance is decreasing, the axial electromagnetic force does not increase. Thus, it is possible to achieve a plateau region where the electromagnetic force does not vary with armature displacement (air gap) size during armature movement.

The shape and position of the magnetic isolation ring are key factors determining the stroke-electromagnetic force characteristics. Tests show that different magnetic isolation ring shapes (angles) result in significantly different stroke-electromagnetic force characteristics.

In this way, by controlling the current, the output electromagnetic force can be controlled.

The electromagnetic force output by the proportional electromagnet acts on a spring, and the valve spool stops at the position where the spring force and electromagnetic force are balanced. In this way, by controlling the current, the valve spool can be moved to and stopped at the desired position, and the valve spool displacement will be proportional to the current.

To control the electromagnetic force output by the armature-sleeve assembly, the current through the coil must be controlled, and there are different ways to control the current through the coil:

In steady state, current through the coil = voltage applied to the coil / coil resistance.

By using adjustable resistance, the power supply voltage can be reduced to the required voltage, applied to the coil, to obtain the required current.

However, adjustable resistance not only consumes energy but also generates heat, which is extremely unfavorable for compact controllers!

PWM (Pulse Width Modulation) is a square wave pulse with fixed amplitude and frequency (period), where only the on-time (pulse width) is adjustable. The ratio of on-time to pulse period is called the duty cycle.

If a switch is added to the coil control circuit, applying the power supply voltage directly to the coil: the switch on-resistance is extremely small, and there is no current when off, so no additional energy is consumed, avoiding the energy consumption and heat generation of voltage-dropping resistors.

Because the coil has inductance, when voltage is applied to the coil, the current changes gradually, and the actual current strength depends on the energization time.

When PWM is applied to the coil, the actual accumulated current depends on the pulse width, and changing the pulse width can change the current. By controlling the on-off time, control of the coil current can be achieved.

Transistor switches can achieve fast PWM; the PWM frequency used for electro-proportional coils is generally 100-600Hz.

As mentioned above, PWM is a square wave pulse technology invented in the 1970s to reduce heat generation. PWM pulse width is not fixed, which is fundamentally different from the fixed pulse width pulses of computer binary digital technology. Calling PWM “digital control” is calling a deer a horse.

The electromagnetic force of proportional electromagnets has a large impact on the performance of electro-proportional valves, so factors that are insignificant in switching electromagnets need to be improved/eliminated:

Magnetic materials exhibit hysteresis: when energized (magnetized) and de-energized (demagnetized), the magnetic field strength is the same but the magnetic flux density is different.

Electrical pure iron has relatively small hysteresis; adding chemical elements can further reduce it, but it cannot be completely eliminated.

In switching electromagnets, the voltage is essentially constant and the armature only stops at limit positions, so hysteresis has little effect; but electro-proportional valves need to control the armature at intermediate positions with frequent current changes, and hysteresis + armature friction force will cause: the stroke-force characteristics do not coincide during closing/opening, and the current-force characteristics do not coincide when current increases/decreases.

Tests have found that allowing small amplitude fluctuations (dithering) of 70-600Hz in the coil current can reduce the effects of hysteresis.

When the coil heats up from current flow, resistance increases; if voltage remains constant, current will decrease and electromagnetic force will be reduced.

Switching electromagnets switch quickly, so changes in electromagnetic force have little effect; but proportional electromagnets rely on stable electromagnetic force and need real-time current monitoring: comparing with the desired current, adjusting PWM pulse width to balance resistance changes caused by temperature and maintain constant current.

Electromagnets have a dead zone: when input current is less than a certain value, the armature does not move and output force is zero.

In switching electromagnet valves, voltage instantly reaches 100%, and the armature will eventually move, so dead zone has little effect; but in proportional electromagnet valves, current increases gradually, and the dead zone for screw-in cartridge electro-proportional valves can reach 15%-30% of the input current.

Dead zone causes include armature hysteresis and friction force between armature and sleeve, so proportional armature-sleeve assemblies require higher machining precision (concentricity, cylindricity, etc.), and friction force can also be reduced through special coatings, glass fiber films, armature bearings, etc.

The armature stroke time for switching electromagnets is 10-100ms; rapid valve spool switching easily causes shock; proportional electromagnets can control gradual changes in electromagnetic force through PWM, allowing the valve spool to move slowly, achieving ramp control (when an input step signal occurs, the controller gradually increases or decreases the output signal according to preset values), avoiding shock.

Open-loop proportional electromagnets are only used for ramp control of pressure/flow (to reduce shock), not for precise position/speed control — because they have inherent nonlinearities such as dead zone, and the valve spool is affected by working condition forces such as friction force and fluid dynamic force, making precise control difficult. Feedback (closed-loop) is needed for accurate control.