Menu

High-performance systems require in-depth examination of their transient performance: ① How large will the overshoot be? ② Can it keep up with commands? How large will the delay be? ③ How long will it take to return to steady state? ④ Will it oscillate continuously? Or even oscillate increasingly worse?

The transient performance of hydraulic components affects the transient performance of the system. The difficulty of hydraulic technology actually lies more in transient behavior: overshoot when relief valves open, starting jumps of flow valves, and especially the vibration of counterbalance valves—all of these lead to various annoying problems such as system shocks, pressure spikes, noise, and oscillations. For these issues, the commonly used damping orifice is merely a panacea, not a cure-all elixir. To achieve better transient performance, it is necessary to learn some system dynamics and automatic control techniques, to thoroughly examine the transient performance of components and systems and study the process, causes, and influencing factors of their transient changes, thereby adopting corresponding improvement measures.

To examine the transient performance of components or systems, the most direct method is to apply an input signal to the examination object and test the output signal, also called the response. Compare the degree to which the output signal follows the input signal: the closer it is to the input signal, the better the transient performance of the examination object.

There are two types of input signals: time domain and frequency domain.

Time domain signals refer to: input signals that change significantly relative to time. The most commonly used is the step signal: increasing from one level to another in the shortest possible time.

By recording input and output signals and analyzing the process, the following can be obtained:

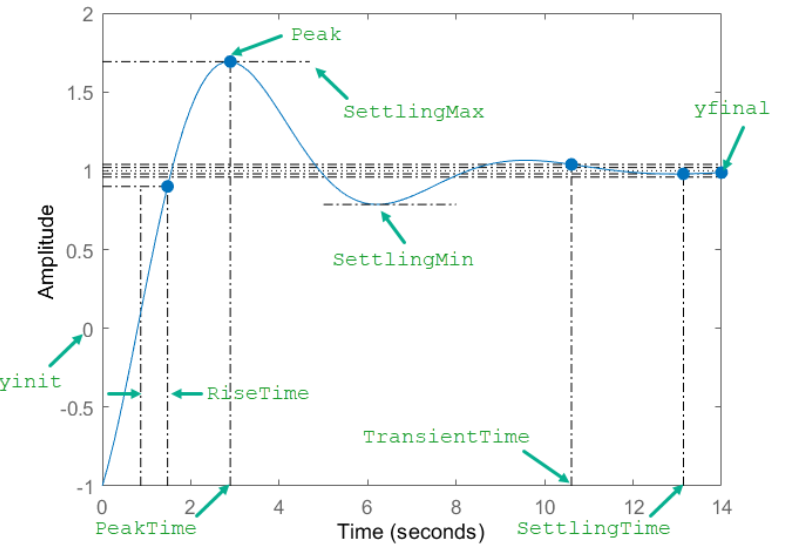

Overshoot — the difference between the maximum value of the output signal and the steady-state value.

Response time — the time for the output signal to reach 90% of the steady-state value.

Settling time — the time to reach when the output signal fluctuation is less than 5% of the steady-state value.

Generally speaking, the smaller the overshoot and the shorter the response time and settling time, the stronger the tracking ability of the examination object, that is, the better the transient performance.

Let the input signal vary as a sine wave over time, and the output should also be a sine wave. If they are similar, then it can be considered to keep up. As the frequency of the input sine wave becomes higher and higher, the output will increasingly fail to keep up: the amplitude will decrease, and the phase will lag behind.

The ratio of the amplitude of the output signal yout to the amplitude of the input signal yin is called the amplitude ratio, and the angle by which the output signal waveform lags behind the input signal is called the phase difference.

Usually, the signal frequency is used as the horizontal axis, and the amplitude ratio and phase difference as the vertical axis to describe the frequency response characteristics of the examination object. Given that the test frequency variation range is very large, the horizontal axis is often expressed in logarithmic form, called a Bode diagram. The frequency at which the amplitude ratio drops to -3dB is called the amplitude bandwidth, and the frequency at which the phase difference reaches 90° is called the phase bandwidth. According to this, the frequency response characteristics of an industrial servo valve: the amplitude bandwidth and phase bandwidth are 110Hz and 180Hz respectively.

The higher the amplitude bandwidth and phase bandwidth, the stronger the tracking ability of the examination object, that is, the better the transient performance.

In the measurement of electronic component systems, because transient performance is generally good, using the time domain would result in extremely short response times and settling times, which is very inconvenient. And the vast majority of electronic components are inherently used to transmit frequency signals, so the frequency domain is basically adopted. For this purpose, corresponding testing instruments have been invented: they can directly generate sinusoidal signals, record output signals, and can change the input signal frequency and record phase differences and amplitude ratios.

In order to predict the transient performance of a system before design, construction, and debugging, people have been trying to conduct theoretical research on transient performance.

This is the foundation for further theoretical research.

In hydraulic systems, pressure, flow, load force, etc. are interrelated. Therefore, to describe hydraulic systems and components in steady state, a set of algebraic equations can be used. For example:

Pressure in a hydraulic cylinder: p = F/A

Flow through an opening: q = CA×√(Δp)

Speed of hydraulic cylinder movement: v = q/A

The solution to the system of equations, if obtainable, is the steady-state operating condition of the system.

In fact, the system condition often continues to change and may be different everywhere, so to describe the system condition in transient state more appropriately, one can only examine a very small, even infinitesimally small volume of fluid, assuming that the relevant parameters are the same within this small volume and remain unchanged for a very short, even infinitesimally short period of time. This must use differential form. For example:

1) Pressing oil with flow rate q into a chamber filled with oil liquid causes a pressure change that can be expressed as: dp/dt = qE/V

2) The oil liquid pushes the piston, overcoming the load force F to move. The change in piston speed over time — acceleration dv/dt — depends on the pressure p, acting area A, and the total inertia m of the piston, piston rod, and load, which can be expressed as: dv/dt = (pA – F)/m

3) The Euler equation here refers to the motion differential equation obtained in 1755 by Swiss mathematician L. Euler by applying Newton’s second law to a fluid element, which brilliantly summarizes the relationship between pressure, position, and velocity at a certain instant for a segment of micro-element volume in the fluid flow, in one-dimensional flow without considering viscosity:

∂p/∂s = ρ×[j×(∂z/∂s) – u×(∂u/∂s) – ∂u/∂t]

Where: p — pressure on the micro-element volume; s — position of the micro-element volume; ρ — density of the micro-element volume; j — unit mass force; z — vertically upward coordinate; u — velocity of the micro-element volume; t — time.

4) The Navier-Stokes equations further brilliantly describe the three-dimensional unsteady motion of viscous compressible fluid micro-elements and can be used for turbulent flow:

∂u/∂t + u×(∂u/∂x) + v×(∂u/∂y) + w×(∂u/∂z) = X – (1/ρ)×(∂p/∂x) + (ν/3)×∂/∂x (∂u/∂x + ∂v/∂y + ∂w/∂z) + ν×(∂²u/∂x² + ∂²u/∂y² + ∂²u/∂z²)

∂v/∂t + u×(∂v/∂x) + v×(∂v/∂y) + w×(∂v/∂z) = Y – (1/ρ)×(∂p/∂y) + (ν/3)×∂/∂y (∂u/∂x + ∂v/∂y + ∂w/∂z) + ν×(∂²v/∂x² + ∂²v/∂y² + ∂²v/∂z²)

∂w/∂t + u×(∂w/∂x) + v×(∂w/∂y) + w×(∂w/∂z) = Z – (1/ρ)×(∂p/∂z) + (ν/3)×∂/∂z (∂u/∂x + ∂v/∂y + ∂w/∂z) + ν×(∂²w/∂x² + ∂²w/∂y² + ∂²w/∂z²)

Where: u, v, w — velocities of the micro-element volume at point (x, y, z); x, y — horizontal direction coordinates; z — vertically upward coordinate; ρ — density of the micro-element volume; p — pressure on the micro-element volume; ν — oil viscosity; t — time.

5) As mentioned in the previous section, to describe the motion of a spool-spring system, a second-order differential equation of spool displacement x is also required.

However, systems of differential equations (especially systems of partial differential equations) are difficult to obtain analytical solutions, which hinders further analytical research on the transient performance of systems.

In response to this obstacle, in order to study the transient performance of electronic components and systems, predecessors invented a complete set of theories for studying using frequency (referred to as frequency domain). This theory adopted the so-called transfer function method.

1) First, linearize the system of differential equations describing the transient state of the examination object.

2) Perform a Laplace transform on the linearized differential equations, converting them into algebraic equations of operator S — transfer functions. Because they have become algebraic equations, they are relatively easy to handle and analyze.

3) Simplify the transfer function. In ideal cases, the amplitude ratio and phase difference of the frequency response of the examination object can be analyzed and compared with measured values.

4) On this basis, system dynamics research can be conducted on the examination object to predict its transient performance (such as natural frequency, damping, response curve, root locus, etc.).

5) On the basis of transfer functions, a series of criteria for judging the stability of examination objects have been further developed (such as Routh stability criterion, Nyquist stability criterion, etc.).

Because most electronic components have good linearity, using the transfer function method is basically feasible. On this basis, so-called PID (P— proportional, I— integral, D— derivative) correction of the difference between the desired value and the feedback value in the controller has also been developed. This is what analog circuits can do and can only do. The above frequency domain methods have accompanied the development of automatic control for nearly a century. Before digital computers, they were very mature and widely adopted technologies in the field of automatic control, with indispensable contributions.

Seventy to eighty years ago, when developing hydraulic servo valves and hydraulic systems using hydraulic servo valves, frequency domain methods (using transfer functions, etc.) were also adopted to determine the frequency response characteristics and stability of hydraulic servo valves and systems. Due to the good linearity of hydraulic servo valves, applications were also relatively smooth.

However, forty to fifty years ago, when developers wanted to use electrohydraulic proportional valves to partially replace hydraulic servo valves, because electrohydraulic proportional valves have much stronger nonlinearity, they began to feel that continuing to use frequency domain methods had considerable limitations.

And the vast majority of ordinary hydraulic valves not only have nonlinearity but also often have many “essential nonlinearities” (dead zones, hysteresis, etc.) that cannot be linearized at all. Therefore, conducting linearized frequency domain research at local points has strong limitations, and the results lack credibility.

Reference [14] Section 7.2 lists the derivation of the transfer function for a subsystem containing a hydraulic cylinder-counterbalance valve, which is quite complex. Interested readers can refer to it.

More than forty years ago, China also made attempts: introducing frequency domain analysis of hydraulic components into university hydraulics textbooks. Not only did students find it difficult to understand, but even many teachers found it difficult. Later, it took several more years to gradually remove this content from textbooks.

1) Although differential equations rarely yield analytical solutions, they can all be converted into difference equations for numerical computation: after giving initial conditions, use an extremely short time (such as 0.0001ms) to replace the infinitely short time in differential equations, calculate the results, and then iterate step by step to obtain approximate numerical solutions.

In this way, state equations (equation systems composed of a mixture of algebraic equations and differential equations surrounding the interaction of key parameters in the operating conditions of the examination object) can also be converted into iteratively computable difference equation systems.

The expressive power of computer programming languages is extremely strong, even exceeding that of common mathematical expressions, and can express all nonlinearities (including those so-called essential nonlinearities). For example, the pressure difference-flow relationship of a check valve can be expressed as:

If p1 ≥ p2 + p0, then q = 0 Otherwise, q = CA×√(p2 – p1)

Similarly, state equations describing the entire hydraulic system can be established, thereby establishing a digital model of the hydraulic system.

Input step and other time domain signals to this digital model, calculate the model’s response to input signals, and determine overshoot, settling time, etc.; after confirmation through actual measurement, the stability of the system can be further assessed.

With the development of computer science, the widespread popularization of computers, and the exponential growth of computing power, this research method has been increasingly widely applied. Digital computational prediction of hydraulic component systems also developed in the late 1970s and is now classified under “digital simulation” (referred to as simulation).

Numerical computation also has limitations: for example, from analytical expressions, it is relatively easy to analyze the influence of various parameters on the process and results; while numerical iterative computation starts from a set of initial parameters and can only obtain one transient change process at a time, and cannot directly see the influence of various parameters. To do this, it is necessary to change the initial value of the parameter to be examined multiple times, and then compare the differences in iterative calculation results to see the influence of that parameter. Therefore, how to change parameters, organize and compare calculation results, and find patterns also requires some thought.

2) Correction

With the tremendous development of large-scale digital integrated circuits (chips), the controllers of servo control systems have also gradually digitized. To obtain better control characteristics, correction links have also been added to the control programs of digital controllers. Although some people still habitually call this correction “digital PID,” in fact its correction capability far exceeds the PID correction composed of analog circuits.

Therefore, for studying hydraulic components and systems, frequency domain methods have been gradually surpassed and have become yesterday’s flowers.

Although computer computing power is super strong, it can only perform calculations based on the mathematical expressions and data given to it by people. As mentioned earlier, many parameters in hydraulic valves are affected by other factors and are difficult to determine accurately, so calculation results are difficult to guarantee accuracy. Therefore, testing is needed for confirmation and correction!