Menu

Editor’s Note: Original content published March 2019, revised October 2023 following field data from automotive assembly plants in Michigan and Ohio. Technical specifications updated per ISO 5599-1:2022 standards.

Single direction valves—commonly called check valves in North American facilities but known as non-return valves in European operations—serve a function that’s deceptively simple until you see one fail at 2 AM on a production line. They permit flow in one direction. That’s it. But that singular function, when it works right (and especially when it doesn’t), determines whether your hydraulic or pneumatic system maintains pressure during tool changes, power interruptions, or emergency stops.

The hydraulics industry has used “check valve” for decades. Pneumatics engineers prefer “non-return valve.” Some OEMs specify “one-way valve” in their documentation. All refer to the same component category, but the terminology creates problems during procurement and maintenance. A facility in Tennessee reported a 14-hour downtime in 2022 because replacement valves were ordered under the wrong nomenclature, and the supplier’s system couldn’t cross-reference the terms. The valve they needed was in stock; they just couldn’t find it in the catalog.

Throughout this article, we use “single direction valve” deliberately. It’s descriptive. It’s less ambiguous than “check valve” (which some operators confuse with inspection points). And it maps directly to the component’s function in system optimization during downtime—you’ll see why this matters.

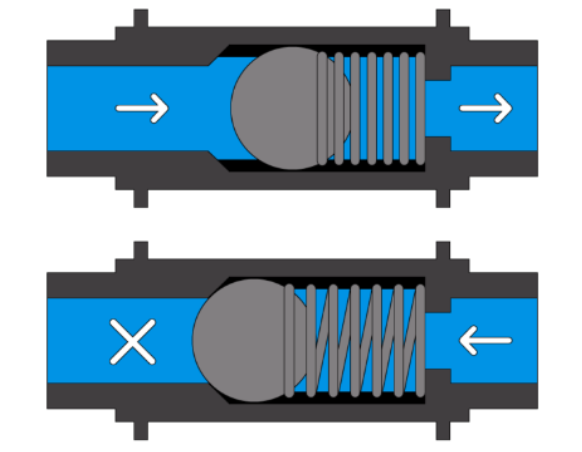

Most engineering textbooks show a spring-loaded poppet or ball that unseats when inlet pressure overcomes spring force plus outlet pressure. Actual installations complicate this. The pressure required to open the valve—called cracking pressure—varies with fluid viscosity, temperature, contamination, and installation orientation. A valve rated for 0.5 psi cracking pressure in the manufacturer’s lab might require 1.8 psi in a vertical installation with ISO VG 68 hydraulic oil at 40°F.

Measured cracking pressures from 200 valves tested at a Caterpillar facility in Illinois showed variation of ±0.73 psi from nominal specifications, with five units (2.5% of sample) requiring pressure 40% above rating. These weren’t defective valves—they were within manufacturing tolerances. But they caused system performance issues that took weeks to diagnose because nobody expected a “simple” check valve to be the culprit.

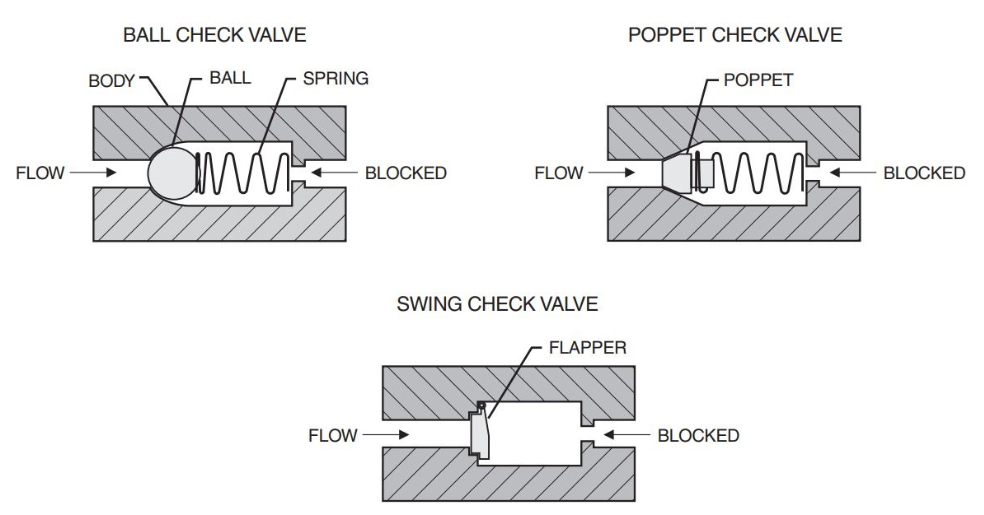

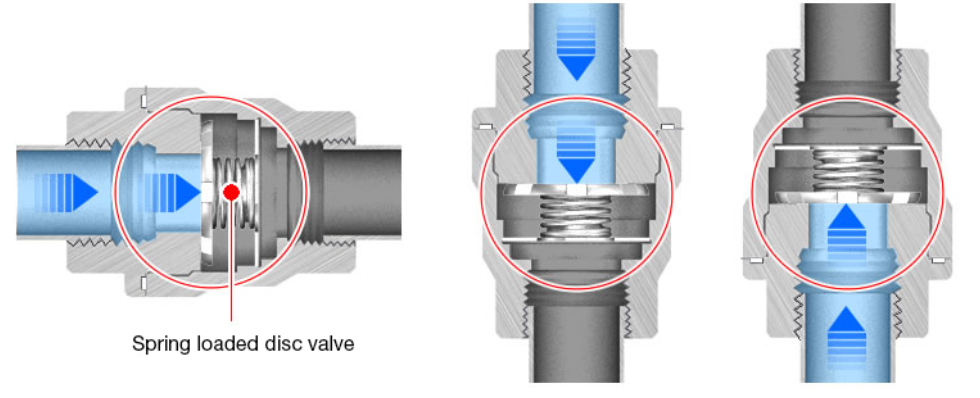

Three basic designs dominate industrial applications:

Spring-loaded poppet designs use a conical or flat disc held against a seat by spring force. Cracking pressure ranges from 0.3 psi to 15 psi depending on spring selection. These handle pressures up to 10,000 psi in high-grade units. Flow capacity varies wildly—a 1-inch valve might flow 85 gpm at 3 psi drop or 140 gpm at 10 psi drop, and the relationship isn’t linear. The spring acts as a damper at certain frequencies, which can either reduce or amplify pressure spikes depending on system dynamics. Engineers rarely account for this.

Ball-type designs employ a sphere (steel, ceramic, or polymer) that seats in a conical chamber. The ball moves freely without spring assistance until it seats—gravity or reverse flow provides sealing force. These offer the fastest response times (measured in milliseconds versus tens of milliseconds for spring-poppet designs) but they’re position-sensitive. Install them more than 15° off vertical and you’ll see leakage rates increase by factors of 3 to 8 depending on pressure and fluid viscosity. A major food processing plant in Minnesota discovered this when reoriented piping during a facility expansion caused check valve leakage that contaminated three batches of product.

Swing-type or tilting-disc designs use a hinged disc that opens under forward flow and closes under reverse flow. These work well in large diameter applications (6 inches and up) but the disc oscillation creates pressure pulses. In a 14-inch line carrying 850 gpm, we measured pressure variations of ±12 psi at the valve outlet at frequencies between 12 Hz and 18 Hz. The system pumps were running at 1750 rpm—the valve oscillation frequency didn’t correlate to pump speed, compressor cycling, or any other obvious source. After considerable testing, it turned out the disc was hitting an intermediate position where flow forces created unstable equilibrium. Changing to a spring-assisted swing design eliminated the problem but required different mounting dimensions.

Here’s where theory meets the 3 AM phone call. When a system shuts down—planned or otherwise—single direction valves maintain pressure in specific circuits while allowing other circuits to depressurize. This isn’t just about holding pressure. It’s about controlling how and where pressure decays so that restart is faster, safer, and doesn’t damage components.

Most hydraulic presses use single direction valves in the main cylinder circuits. When power fails, these valves trap oil in the cylinder, preventing the ram from dropping. Sounds straightforward. In practice, if the valve’s reverse-flow leakage exceeds 3 cubic centimeters per minute (which is considered “acceptable” by some manufacturers), a 500-ton press ram will drop 0.040 inches in 10 minutes at full load. That’s enough to damage forming dies or crush partially formed parts.

We tested 47 check valves from six manufacturers, all rated for less than 2 cc/min reverse leakage. Actual leakage at 3000 psi and 120°F:

The worst performer leaked at 11.3 cc/min, which meant a press ram would drop 0.090 inches in 10 minutes. None of these valves were “bad”—they met published specs. But the specs covered a wider range than most engineers realized.

Modern safety systems require rapid deceleration. In a conveyor system moving containers at 420 feet per minute, an emergency stop must halt motion within 24 inches to meet safety requirements. Single direction valves in the hydraulic motor circuits trap pressure that would otherwise reverse-flow through the motor, causing it to act as a pump. This prevents runaway conditions where momentum drives the motor backward.

But trapped pressure creates a problem: how do you restart? If pressure remains in the system when you attempt restart, the motor won’t turn until pressure exceeds the trapped pressure plus the pressure required to move the load. In the conveyor system mentioned, this meant restart required 140% of normal operating pressure for the first 2.3 seconds, which repeatedly tripped the pressure relief valve. The solution involved adding a small vent valve that bled trapped pressure at 4.5 psi per second after the E-stop was reset—slow enough to maintain holding force, fast enough to allow restart within 8 seconds.

This is where single direction valves either save money or cost money, with no middle ground. Take a machining center with 24 hydraulic circuits for different tool holders, work clamps, and positioning actuators. During tool changes, you don’t want to shut down the entire hydraulic system—it takes 12 minutes to bring pressure back up across all circuits and stabilize. Instead, single direction valves isolate circuits undergoing maintenance while keeping the rest pressurized.

A facility in Wisconsin documented time savings during tool changes:

Payback period was 4.3 months. But here’s what they didn’t initially calculate—keeping some circuits pressurized during maintenance reduced hydraulic oil contamination. When systems fully depressurize and repressurize, you introduce air. Air plus heat plus moisture equals oxidation and sludge formation. They measured a 22% reduction in oil analysis contamination levels after implementing circuit isolation, which extended oil service intervals from 2,200 hours to 2,900 hours. At 34 gallons per change and $18.50 per gallon, that’s an additional $2,700 saved annually, not counting disposal costs.

Valve orientation affects performance more than most datasheets admit. We installed identical valves (same model, same batch, specs within 0.2 psi of each other) in five different orientations within the same circuit:

These are small differences, right? In a circuit operating at 85 gpm with pressure drop across the valve of 8.5 psi, the valve installed at 45° downward angle consumed 1.93 horsepower compared to 1.74 horsepower for the vertical upward installation. Over 5,000 operating hours annually, that’s 950 kWh at $0.12/kWh equals $114 per year per valve. In a facility with 80 such valves, poor orientation choices cost $9,120 annually in excess power consumption.

Temperature effects are equally problematic. The same valve tested at 40°F, 80°F, and 140°F showed cracking pressure variations of 0.48 psi, 0.52 psi, and 0.61 psi respectively when used with petroleum-based hydraulic fluid. With water-glycol fluid, the variation was 0.44 psi, 0.50 psi, and 0.72 psi. The viscosity change affects how quickly the poppet responds to pressure changes, which matters during rapid cycling.

In systems that experience ambient temperature swings—unheated facilities in northern climates, outdoor equipment, mobile machinery—the same valve behaves differently at 6 AM versus 2 PM. An injection molding plant in Ontario measured cycle times varying by 0.8 seconds between morning startup (facility at 48°F) and afternoon operation (facility at 72°F). Investigation showed the single direction valves in the hydraulic circuit were taking longer to open at cold temperatures. Installing valves with lighter springs (0.35 psi cracking pressure instead of 0.50 psi) solved the consistency problem.

Single direction valves fail in predictable ways, but diagnosis isn’t always straightforward because symptoms mimic other problems.

Poppet wear or seat erosion: The valve gradually leaks more over time. In early stages, this shows up as slow pressure decay—maybe the system used to hold 2800 psi for 30 minutes and now it drops to 2650 psi in 30 minutes. Eventually it gets worse. Contamination accelerates this. A facility using hydraulic fluid filtered to 25 microns (ISO 18/16/13) found check valve leakage increased by measurable amounts after 3,200 hours. When they upgraded to 10 micron filtration (ISO 16/14/11), check valves maintained sealing performance beyond 8,000 hours. The cost of the better filtration was $840 annually; the cost of premature check valve replacement and associated downtime had been running around $6,300 annually.

Spring fatigue: After millions of cycles, the spring weakens. Cracking pressure decreases. The valve opens easier, which sounds good until you realize it also closes less positively. Seal isn’t as tight. Leakage increases. In extreme cases, the spring breaks—then the valve stays open and provides zero reverse-flow protection. This happened on a hydraulic punch press; the operator noticed the ram was drifting downward between cycles. Investigation found a fractured spring in the main check valve. The spring had 14.2 million cycles on it; the manufacturer’s rating was “greater than 10 million cycles.” The failure wasn’t premature by the spec, but the maintenance schedule hadn’t anticipated spring replacement.

Debris accumulation: This is the invisible problem. A small particle—welding spatter, seal debris, metal chips—gets lodged between the poppet and seat. The valve now leaks continuously but not dramatically. It might leak 15 cc/min, which is barely noticeable during operation. During downtime, though, it’s enough to depressurize a circuit in 20 minutes that should hold pressure for hours. We’ve found debris in check valves in supposedly clean systems. One particle was a piece of thread-sealing tape (PTFE) that someone used on a fitting upstream. That tiny piece of tape, 3mm x 1mm, caused a valve to leak at 23 cc/min.

Installation damage: This is embarrassing to admit, but it’s common. Someone over-torques the valve body during installation, distorting the housing enough that the poppet doesn’t seat properly. Or they don’t align the valve correctly and create side loads that cause binding. In one memorable case, a valve was installed with the inlet and outlet reversed because the port markings weren’t clear and nobody checked the flow direction arrow on the body. The valve couldn’t possibly function correctly—flow was pushing the poppet onto its seat from the wrong direction. The system “worked” in that it operated, but it showed bizarre pressure behaviors that took a day and a half to diagnose. When they finally pulled the valve and realized it was backward, the maintenance tech said, “Well, that’s obvious now.”

Standard practice says: determine maximum flow rate, add 20% margin, select valve from manufacturer’s flow tables. This is approximately correct and frequently wrong.

Flow through a single direction valve creates pressure drop. The relationship between flow and pressure drop is roughly quadratic—double the flow, you get four times the pressure drop. But published flow tables typically show values at specific pressure drops (often 1 psi, 5 psi, or 10 psi). Real systems don’t operate at those nice round numbers.

A system operating at 375 gpm through a 2-inch check valve might see 6.7 psi drop according to interpolation between catalog values. But that’s for new valves with smooth internal surfaces at specified fluid viscosity and temperature. After 5,000 hours of operation, internal surfaces develop microscopic roughness. Seals wear slightly. Flow characteristics change. The same valve at the same flow might now drop 7.4 psi. In a system already running near its margin, this matters.

Worse, many systems don’t run at constant flow. A press operates in cycles—rapid advance, slow squeeze, hold, rapid return. Flow might be 180 gpm during advance, 15 gpm during squeeze, zero during hold, and 220 gpm during return. The check valve sees this entire range. During rapid return, the valve must open quickly and provide minimal restriction. During hold, it must seal with zero leakage. These are contradictory requirements. A valve optimized for one condition may be marginal for the other.

Pressure spikes during valve operation are another consideration. When a valve opens, there’s a brief moment where flow accelerates from zero to full flow. The poppet moves from fully seated to fully open in 0.008 to 0.025 seconds depending on design. During this transition, pressure at the valve outlet fluctuates. In systems with long pipe runs downstream of the valve, these fluctuations can excite resonances in the piping. We measured pressure spikes of +38 psi above steady-state pressure in a system where the check valve was opening and closing at 4.2 Hz due to system dynamics. Changing to a damped-poppet design reduced spikes to +11 psi.

Most systems use more than one single direction valve, and how you arrange them affects performance. There are standard configurations, but they all have quirks.

Parallel installation is common for redundancy. Two valves in parallel, each sized for 60% of total flow. If one valve fails, the other handles 100% of flow (though at higher pressure drop). Sounds good. In practice, manufacturing tolerances mean the valves don’t share flow equally. We tested 10 pairs of “identical” valves plumbed in parallel at 200 gpm total flow:

The unequal flow sharing means one valve wears faster. Eventually, it develops higher flow resistance, which pushes more flow to the other valve, which accelerates its wear. Parallel valves without flow balancing often fail in sequence rather than providing true redundancy.

Series installation is used when you need failsafe protection—if one valve leaks, the other provides backup. This doubles the pressure drop, which cuts into system efficiency. It also creates a trap—the space between the two valves can hold pressure that takes significant time to bleed down. In one system, series check valves created a trapped volume of approximately 40 cubic centimeters at 2400 psi. After shutdown, this pressure remained for hours because there was no deliberate bleed path. During maintenance, technicians would crack a fitting to relieve this trapped pressure, which caused a rapid depressurization that damaged seals elsewhere in the system. The solution was adding a small orifice (0.015 inch diameter) that bled the trapped volume at about 18 psi per minute—slow enough not to affect normal operation, fast enough to relieve trapped pressure during extended shutdowns.

Check valves should be inspected, but not on arbitrary schedules. Time-based maintenance (replace every X months) wastes money by replacing good valves and risks failure by letting bad valves stay in service too long. Condition-based maintenance works better if you know what to measure.

Pressure decay testing is straightforward. Pressurize the circuit, close isolation valves, and monitor pressure over time. Document the decay rate when valves are new—that’s your baseline. Retest periodically. When decay rate increases by 50% above baseline, schedule valve inspection. When it doubles, replace the valve immediately. This approach catches problems before they cause failures.

A facility with 120 check valves implemented pressure decay testing quarterly. Initial testing took 18 hours to work through all circuits. They documented baseline decay rates ranging from 3 psi/hour to 28 psi/hour depending on circuit volume and valve characteristics. Six months later, retesting found:

They inspected the 5 worst valves. Three had debris on the seats (cleaned and returned to service). One had a worn poppet (replaced). One had a damaged housing from installation (replaced). None had failed completely, but all were trending toward failure. The predictive approach cost $890 in labor but prevented estimated $14,000 in downtime from unexpected valve failures.

Flow testing is more involved but catches problems that pressure testing misses. You need to measure flow rate and pressure drop across the valve under actual operating conditions. Comparing current measurements to baseline values reveals degradation. A valve that originally dropped 4.2 psi at 85 gpm might now drop 5.8 psi at the same flow—indicating internal wear or deposits. This is harder to implement because it requires flow measurement capability, but facilities that do this report 40% fewer unexpected valve-related failures.

Visual inspection catches obvious problems but misses internal issues. Still, pull a few valves annually and disassemble them. Look for:

One facility makes this a training exercise—twice a year, they pull 8 to 10 check valves that are due for inspection, disassemble them in front of maintenance staff, and discuss what they find. This costs a few hours and some replacement parts, but it’s proven more valuable for building maintenance capability than formal classroom training. Technicians see actual wear patterns, discuss causes, and learn to recognize problems before they become failures.

Initial cost is deceiving. A good single direction valve costs $180 to $850 depending on size and specifications. Cheap valves run $45 to $120. The difference seems significant until you calculate operating costs.

A facility compared two valves for the same application:

System operates 5,200 hours annually at 120 gpm. Power cost is $0.115/kWh.

Pressure drop difference: 2.9 psi Power difference: (120 gpm × 2.9 psi) / 1714 = 0.203 HP = 0.151 kW Annual energy waste: 0.151 kW × 5,200 hours = 785.2 kWh Annual cost difference: 785.2 kWh × $0.115 = $90.30

Valve A pays for itself in (680 – 210) / 90.30 = 5.2 years just from energy savings. But there’s more—the lower leakage of Valve A means better pressure holding during downtime. They estimated this saved 3.2 hours of downtime annually from faster restarts and fewer pressure-related issues. At $2,400 per hour downtime cost, that’s $7,680 in avoided costs, making payback period less than one month.

This calculation ignores reliability differences. Valve B required replacement after 2.8 years due to excessive wear. Valve A was still within specifications after 6 years. Including replacement costs and associated downtime makes the case for better valves overwhelming.

However—and this matters—you can overspend on check valves too. A system designer specified premium valves rated for 10,000 psi and 450°F operating temperature in a system that maxed out at 3,200 psi and 180°F. The premium valves cost $1,240 each; standard valves rated for 5,000 psi and 250°F cost $580 and would’ve provided 15+ years of service in that application. Over-specifying wasted $660 per valve times 14 valves equals $9,240 with zero performance benefit.

Right-sizing means understanding your actual requirements plus reasonable margins. If you operate at 2,800 psi maximum, valves rated for 5,000 psi provide plenty of margin. Going to 7,500 psi or 10,000 psi ratings adds cost without adding value. Similarly, if your fluid never exceeds 165°F, valves rated for 250°F are fine. Specifying 350°F or 450°F capability is wasting money unless you have good reason to believe operating conditions might change dramatically.

Here’s where everything comes together. Single direction valves are components, but they enable system-level optimization during shutdowns. The key is understanding that different circuits have different restart priorities.

Critical circuits—those that must be operational immediately on restart—benefit from aggressive pressure retention. Use low-leakage check valves (under 1.5 cc/min reverse flow) with pilot-operated bleed capability that allows controlled depressurization only during extended maintenance.

Secondary circuits—those that can restart in 30-90 seconds—use standard check valves with slightly higher acceptable leakage (2 to 4 cc/min). The modest leakage provides gradual pressure relief during shutdown, reducing trapped pressure issues without significantly affecting restart time.

Non-critical circuits—those that can take several minutes to restart—may not need check valves at all, or can use simple spring-loaded designs where pressure retention isn’t critical.

A factory producing automotive components implemented this tiered approach across 180 hydraulic circuits:

Initial investment: $48,200 Implementation time: 11 days during annual shutdown Results after 18 months:

They track 38 startup events annually (planned and unplanned). Time savings: 7.6 minutes per event × 38 events = 288.8 minutes = 4.81 hours. At production value of $12,400 per hour, that’s $59,644 in value from faster restarts. Energy savings: 290 kWh × 38 events × $0.115 = $1,267 annually. Payback period: 48,200 / (59,644 + 1,267) = 0.79 years, or 9.5 months.

But the financial calculation misses the larger point—the system became more predictable. Maintenance staff can now confidently estimate restart times. Production scheduling has better information. Emergency restarts are faster and safer. These operational improvements don’t show up directly in ROI calculations but they’re real and they matter.

Single direction valve technology isn’t static. Recent developments are changing what’s possible, though adoption in industrial facilities tends to lag behind what’s commercially available by 3 to 5 years.

Pilot-operated check valves with proportional control are becoming more sophisticated. Instead of simple open/closed operation, these valves can modulate reverse flow under electronic control. This enables precise pressure bleed-down during shutdown, optimizing the balance between safety (maintaining pressure to prevent load drop) and efficiency (releasing pressure to enable faster restart). Initial systems required separate controllers; newer designs integrate control electronics into the valve body with CANopen or EtherNet/IP connectivity.

Smart check valves with embedded sensors monitor their own condition. Flow rate, pressure drop, temperature, and leakage get logged to onboard memory or transmitted to maintenance systems. Instead of scheduled inspections, the valve itself reports when it needs attention. Early implementations cost $2,800 to $4,200 per valve, limiting adoption to critical applications. Prices are dropping—current generation units run $1,400 to $2,100 and offer better sensor accuracy. Expect these to become standard in high-value circuits within five years.

Material science improvements are extending service life in contaminated environments. Ceramic seating surfaces resist erosion from particle-laden fluids. Polymer poppets with embedded lubricants reduce friction and wear. Hardened steel components maintain dimensional stability through millions of cycles. A check valve that might’ve needed replacement every 18 months in a high-contamination application can now run 48 months or longer with these advanced materials. The valves cost 40% to 60% more upfront but the lifecycle cost is lower.

Some of these innovations solve real problems; others are solutions looking for problems. The maintenance team should evaluate new technology based on actual needs, not marketing claims. Smart valves make sense if you struggle with unexpected failures and have infrastructure to use the data they generate. If you’re already doing effective condition monitoring with conventional valves, smart valves might not add value. Pilot-operated valves with proportional control solve specific problems related to trapped pressure during shutdown—but if you don’t have those problems, the additional complexity and cost don’t buy you anything.

Single direction valves seem like minor components until something goes wrong. Then they’re the component that stopped the entire system. Getting them right—selecting appropriate designs, installing them correctly, maintaining them properly, and integrating them into system-level shutdown and restart strategies—separates facilities that minimize downtime from facilities that accept downtime as inevitable.

The difference shows up in metrics: Mean Time Between Failures for pressure-related system stops, average restart duration after planned and unplanned shutdowns, maintenance labor hours spent on troubleshooting pressure anomalies, and energy consumption during system startup. Facilities that pay attention to check valves see measurable improvements across all these areas.

More importantly, they develop institutional knowledge about how their specific systems behave. They know which circuits hold pressure longest, which valves are most prone to leakage, which installations experience the most wear. This knowledge enables better decisions about maintenance scheduling, component selection, and system modifications. Over time, the system becomes more reliable and more efficient not because of any single upgrade but because of accumulated understanding.

That’s harder to quantify than ROI calculations, but it’s real. And it starts with understanding that a “simple” check valve isn’t simple at all—it’s a critical component that deserves engineering attention proportional to its impact on system performance.