Menu

The most commonly used component in electrohydraulic valve control is the solenoid electromagnet. Since Faraday’s discovery of electromagnetic induction in 1831, practical electrical devices began to emerge. The German Schultz Electromagnet Company has been professionally manufacturing electromagnets since 1912.

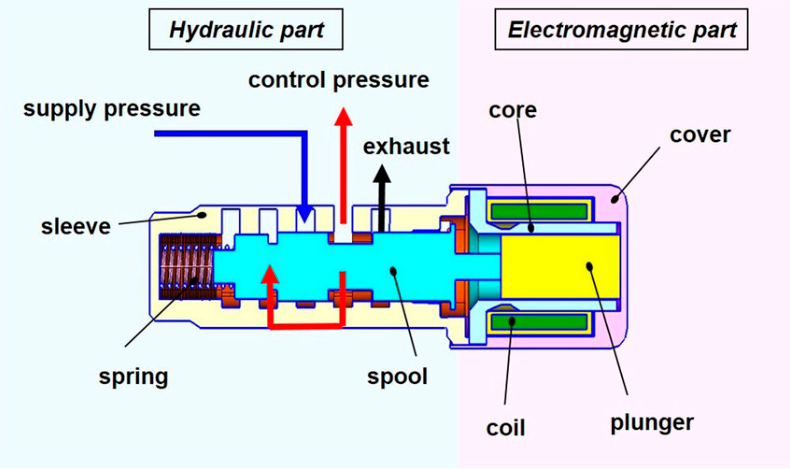

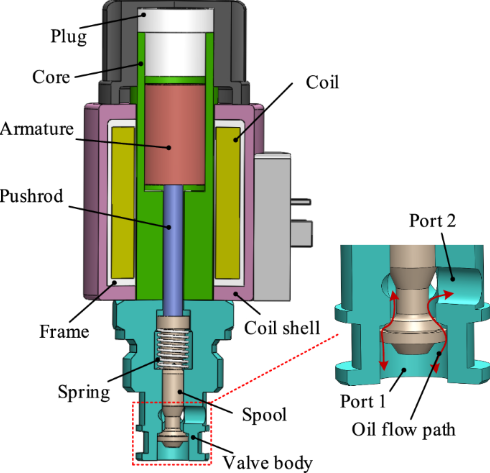

A solenoid electromagnet consists of a coil and an armature sleeve assembly. When voltage is applied to the coil, current passes through the coil to generate a magnetic field. The armature sleeve assembly produces electromagnetic force in the magnetic field, which then operates the valve spool through a push rod or pull rod. Since the armature operates the valve spool through push or pull rods, the armature sleeve assembly is often integrated with the valve.

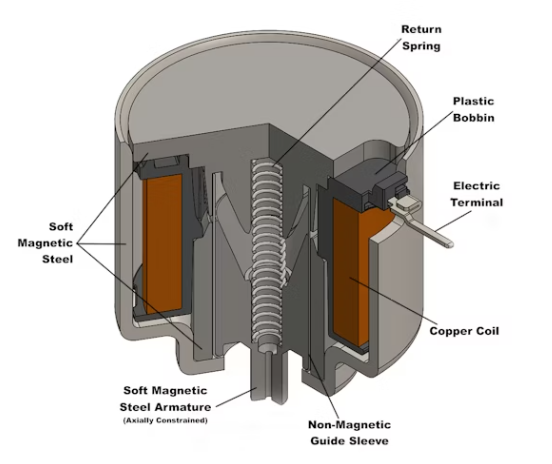

The coil consists of wire windings, plastic encapsulation, a magnetic conductive sleeve, and lead-out terminals:

Wire windings: Made by winding heat-resistant enameled wire on a bobbin;

Plastic encapsulation: Used to fix, seal, and protect the wire windings;

Magnetic conductive sleeve: To reduce magnetic resistance and concentrate the magnetic field, the windings are fitted with a thick magnetic conductive sleeve with good magnetic conductivity and low residual magnetism (generally made of pure electrical iron), available in internal and external mounting types — the internal type is close to the windings with high magnetic conduction efficiency, but iron and plastic have different thermal expansion coefficients, making thermal expansion and contraction prone to creating gaps; the external type wraps around the plastic encapsulation, has good heat dissipation performance, and can reduce mechanical damage, suitable for mobile equipment outdoor operations, and increased thickness can compensate for magnetic conduction efficiency;

Lead-out terminals: Connected to the wire windings for introducing current.

A magnetic field is generated around a current-carrying conductor, with field strength proportional to current intensity;

When wire is wound into a solenoid, the generated magnetic fields superimpose and strengthen each other, with field strength proportional to the number of coil turns and inversely proportional to the solenoid length;

The electromagnetic force generated by the armature in the coil is proportional to the current, so controlling the current can control the force acting on the valve spool;

Using thicker wire and increasing the number of turns can achieve greater electromagnetic force at the same voltage and current, but this increases coil volume and cost.

Solenoid valve coils are generally designed for 100% duty cycle (continuous operation).

After the coil is energized, except for a small amount of mechanical work done when first energized to move the armature, the remaining current is converted to heat, making heating and temperature rise inevitable. As the temperature difference between the coil and surrounding environment increases, heat dissipation also increases. When heat generation and dissipation reach equilibrium, the coil temperature stops rising. This equilibrium temperature depends both on heat dissipation conditions (such as coil surface area) and ambient temperature.

The wire exterior has a layer of insulation paint, with different classes of maximum heat resistance temperature. The thermal equilibrium temperature of coils is typically 100K higher than ambient temperature, so the enameled wire used in hydraulic valves should have a heat resistance class of at least F class (heat resistant to 155℃), with H class (heat resistant to 180℃) and N class (heat resistant to 200℃) also being used.

Given that solenoid surface temperatures may be very high, protective measures must be considered to prevent operators from being burned by contact with the coil.

Both AC voltage and DC voltage applied to the coil can generate a magnetic field, but AC coils have a drawback: if the armature does not reach the closed position during switching, current will rise sharply and may even burn out the coil. Therefore, modern solenoid valves commonly use DC power. Some manufacturers’ coils contain full-bridge rectifier circuits and can be directly connected to AC power sources; for solenoid valves without rectifier circuits using AC power, the terminal must have a rectifier circuit.

Additionally, even for nominally DC power supplies, quality must be checked. If the AC component (rectification ripple) exceeds 5%, it may cause coil burnout.

Coil voltage types generally provided by suppliers include: DC 12V, 24V; AC 110V (115V), 220V (230V). Some manufacturers can also provide DC 10V, 36V, 48V, 110V and AC 24V, and accept orders for DC 6V, 20V, 30V, and 72V.

For the same manufacturer’s coils, when power is the same but voltage differs, assembly dimensions are generally consistent to facilitate interchangeability.

For mobile hydraulic equipment, the power source is typically a battery (DC power). Lead-acid battery voltage is commonly 24V, but when an internal combustion engine drives a generator to charge the battery, voltage will increase (sometimes reaching 28V) and may contain AC components, requiring attention to compatibility; new energy battery voltages differ and also require corresponding matching.

Furthermore, the wire from the battery to the controller, then through switches to the coil, causes voltage drop, which should be checked during use.

Coil resistance increases with temperature rise, causing working current to decrease and electromagnetic force to drop, potentially affecting operation.

Standards suggest allowing ±10% deviation in operating voltage. Some manufacturers’ products allow ±15% deviation, while others claim their products allow ±20% deviation in operating voltage.

In practice, the voltage at which coils can maintain normal operation is related to ambient temperature: slightly high voltage has little impact; when voltage is insufficient, operation is still possible at lower ambient temperatures, but not at higher ambient temperatures.

When winding wire turns using ordinary round cross-section enameled wire on a cylindrical bobbin, winding quality depends on the rigidity of the enameled wire and the quality of the winding machine. Generally, after winding 5 or 6 layers, neat winding becomes difficult and gaps between wires increase.

After the coil heats up during operation, air in the wire turns expands and pressure increases, rushing out through gaps between lead-out terminals and plastic encapsulation and other crevices; when the coil stops working and temperature drops, internal pressure decreases and air is drawn in through the gaps — this is the coil “breathing” phenomenon. This phenomenon brings moisture and other corrosive substances into the coil. Over time, gaps become larger and the insulation paint of the enameled wire gradually deteriorates.

To address the “breathing” phenomenon, plastic encapsulation is often made from a mixture of nylon 30 and nylon 50 containing reinforcing fibers in appropriate proportions, providing appropriate elasticity while ensuring rigidity; some manufacturers pre-machine wire grooves on the bobbin to achieve neat winding of more layers, reducing air in the wire turns and weakening the “breathing” phenomenon.

Using flat copper wire to wind coils can also reduce gaps between wires; some manufacturers, after coil winding is complete, first evacuate air from the wire turns through vacuum pumping, then allow insulating oil to enter and fill the gaps, essentially eliminating the “breathing” phenomenon.

Electricity and magnetism interact: electricity generates magnetism, magnetism generates electricity. In coils, wires are densely wound together, and after energization, the generated magnetic fields interact with each other. While the magnetic field generated by the coil acts on the armature, the armature also reacts on the magnetic field, changing it. The coil’s induction of the magnetic field is called the coil’s inductance. The coil’s inductance generates back electromotive force when voltage is applied to the coil and when the armature moves, resisting current changes.

The energization/de-energization process is divided into several stages:

In the initial stage after voltage is applied to the coil, due to the coil’s inductance, current only increases slowly. At this time, the electromagnetic force is still less than friction force, and the armature does not move. This stage is called the dead zone;

After the dead zone stage, electromagnetic force exceeds friction force and the armature begins to move. The current at this time is called dead zone current. With armature movement, the back electromotive force of electromagnetic force increases and may even cause current to decrease briefly;

The time for the armature to complete its full stroke is generally 10-100ms, after which current gradually increases again until reaching steady-state value (voltage applied across the coil divided by coil resistance);

When the coil is de-energized, current is suddenly cut off. Due to the coil’s inductance, the coil generates a very high reverse voltage surge, with peak values exceeding 20 times the rated voltage or more, subjecting the enameled wire insulation layer to severe testing.

Adding a reverse diode to the coil can significantly reduce the reverse voltage peak, but note: ordinary coils are non-polar, but with a diode they become polar, and wiring must follow the specified polarity, otherwise current will short circuit through the diode and burn out the coil.

Electron movement differs from mechanical movement and has no wear, so theoretically coil life is infinite. However, in practice coils always fail, and this is one of the main causes of solenoid valve failure. Specific causes and prevention measures include:

The aforementioned “breathing” phenomenon can be addressed through optimized winding and encapsulation methods;

Over-tightening the coil fixing nut may damage the coil plastic encapsulation or even the magnetic conductive sleeve, causing cracks. Some products use nuts with rubber rings to increase friction force, so the nut does not need to be tightened very much and there is no worry about loosening;

Corrosion of the armature sleeve will damage coil plastic encapsulation. For products in outdoor or corrosive gas environments, the sleeve should have a protective layer (zinc or zinc-nickel plating), and O-rings should be placed at both ends of the coil to prevent water from penetrating between the coil and sleeve;

Damage from impact by foreign objects requires strengthened protection;

Terminals commonly used in indoor hydraulics are not suitable for outdoor environments, as there are always tiny gaps between metal lead-out terminals and plastic encapsulation. If waterproof rings are not installed properly or are missing, water may enter the coil interior through the gaps;

Over-tightening fixing screws may pull the nut out of the plastic encapsulation, damaging the encapsulation.

Water (especially water containing impurities and chemical solvents) damages electrical equipment, so relevant standards specify waterproof and dustproof ratings:

IP65 requirement: Can prevent dust entry and withstand low-pressure water jet impact from 3m away;

IP67 requirement: Can prevent dust entry and can be immersed in 1m deep water for 30 minutes without damage;

IP69K requirement: Can prevent dust entry and withstand high-pressure (10MPa), high-temperature (80℃) water jet mixed with detergent impact from 10-15cm away.

Different terminal forms can achieve corresponding waterproof and dustproof ratings. Some terminals can achieve IP65, IP67, or IP69K. Double-wire form terminals can also achieve IP69K, but care must be taken to prevent water from entering through gaps between wire insulation sleeves and metal wires.

Due to corrosion and high-temperature aging of insulation layers, enameled wire in coils will gradually develop inter-turn short circuits. When there are few inter-turn short circuits, the coil can still work, but as inter-turn short circuits increase, coil resistance decreases, current through the coil increases, and heating at short-circuit locations is particularly concentrated, accelerating coil damage. This damage is not immediately visible from the outside, and the coil may suddenly burn out.

To address this, coil resistance can be checked regularly. If a coil’s resistance has decreased by more than 10% from normal values, even if it can still work, it should be replaced promptly (note that coil resistance changes with temperature, and this factor should be considered during measurement).

More advanced programmable logic controllers (PLCs) can monitor output current at each output port. If the PLC can simultaneously detect operating time and ambient temperature, with appropriate algorithms, it can achieve early warning of coil damage.

Chinese mechanical industry standards make some recommendations for electromagnet testing. To discover weak points, some manufacturers conduct more rigorous testing:

Thermal shock testing: The coil is first heated to 105℃ and held for 2 hours, then placed in 5℃ water and soaked for 2 hours. After repeating 10 times, normal operation is required. This test simulates the sun and rain environment that agricultural and construction machinery may encounter;

Other tests: Include salt spray testing, dust resistance testing, vibration testing, impact testing, corrosion resistance testing, drop testing, storage temperature testing, moisture resistance testing, water penetration resistance testing, overvoltage testing, surge testing, high-pressure water jet impact testing, simultaneous voltage-temperature-humidity variation testing, etc. These tests simulate various extreme situations that may be encountered in actual applications.

Coils that can pass these tests and still work normally afterward indicate good quality. Even if coil manufacturers do not have the capability to perform all tests, they should select the most important items for testing based on users’ actual working conditions, or conduct comparative testing with existing products to study improvements.

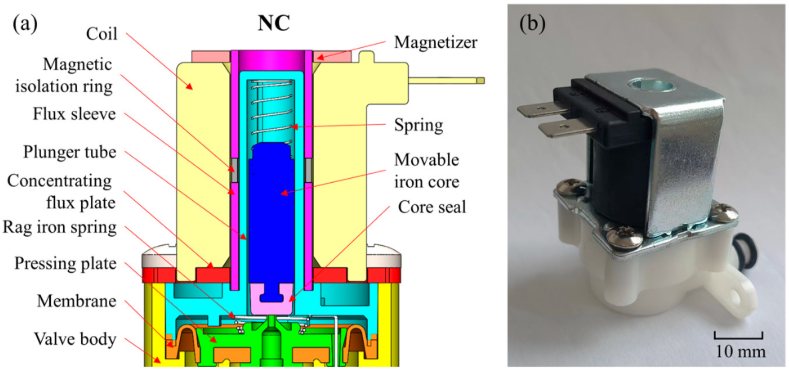

The armature sleeve assembly can generate push or pull force in a magnetic field.

The armature sleeve assembly mainly consists of a sleeve, armature, and push rod or pull rod, divided into dry and wet types:

Dry type: Has a seal ring on the push rod that prevents pressure oil from entering the sleeve, but the seal ring creates friction force;

Wet type: Pressure oil can enter the sleeve. The advantage is avoiding friction force from seal rings, and the armature immersed in oil also reduces friction. Heat generated by the coil can also be partially carried away by oil flow, but this means the armature sleeve assembly must withstand pressure to a certain extent, especially the connection between the non-magnetic ring and guide sleeve (commonly using copper brazing, argon arc welding, or vacuum welding) must be very reliable.

When a magnetic field is applied to a material, the material’s magnetic induction intensity changes: when magnetic field strength increases and decreases, the material’s magnetic induction differs. At the same magnetic field strength, the difference in the material’s magnetic induction intensity is called hysteresis; after the magnetic field strength drops to zero, the magnetic induction intensity that the material still possesses is called residual magnetism.

According to magnetic field induction performance, metallic materials can be divided into three categories:

Ferromagnetic materials: Responsive to magnetic fields, with large residual magnetism, such as permanent magnets;

Paramagnetic materials: Responsive to magnetic fields, with minimal residual magnetism, such as pure electrical iron;

Diamagnetic materials: Minimal response to magnetic fields, such as copper, aluminum, gold, silver, austenitic stainless steel, etc.

Pole pieces and armatures are made of paramagnetic materials, while non-magnetic rings are made of diamagnetic materials. This forces all magnetic field lines to pass axially through the air gap, generating electromagnetic attraction force in the axial direction.

The relationship between electromagnetic force and hydraulic force versus load force is completely different: hydraulic force is determined by load force — the magnitude of load force determines hydraulic force, and without load force there is no hydraulic force; whereas electromagnetic force is completely independent of load force.

As the armature moves, the air gap decreases, local magnetic resistance decreases proportionally, and magnetic force increases inversely. This characteristic is called the stroke-magnetic force characteristic (similar to two magnets: as the distance between them decreases, magnetic force increases sharply).

If the end faces of the armature and pole piece are made conical, due to increased magnetic conduction area, the stroke-magnetic force characteristics will differ: electromagnetic force is greater than that of flat end faces at larger strokes; at very small strokes, it is less than that of flat end faces, but conical manufacturing costs are higher.

Solenoid electromagnets have two working modes: push type and pull type. Generally, the same coil is used, with only slight differences in armature structure; three-position valves generally use two coils, one push and one pull.