Menu

When a 40-ton excavator lifts a steel beam with millimeter precision, or when a manufacturing press applies exactly 2,000 PSI to shape metal components, a cylindrical mechanism inside a valve housing orchestrates every movement. This mechanism—the spool within a hydraulic valve—transforms pressurized fluid into controlled mechanical force by opening and closing internal pathways in response to operator commands or automated signals.

Hydraulic power transmission relies on fluid’s incompressibility to transfer force across distances and through complex machinery. In both hydraulic systems using oil and pneumatic systems using air, spool valves control flow direction by switching the paths through which the fluid travels. The valve serves as the decision point where system intelligence meets mechanical action.

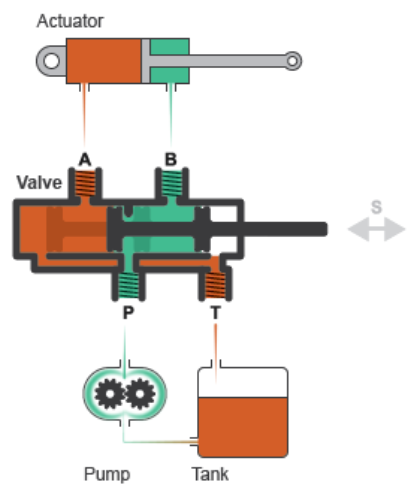

The control function centers on three parameters: flow direction, flow rate, and pressure distribution. A mobile equipment operator pulling a lever sends a signal that repositions the spool, which then redirects fluid from a pump through specific ports to extend a hydraulic cylinder. When the operator releases the lever, spring mechanisms or opposing solenoids return the spool to neutral, halting fluid flow and locking the cylinder in position.

The spool is a cylindrical component inside a directional control valve that shifts between positions to open, close, or redirect hydraulic flow through different ports. This shifting action happens within clearances measured in microns—typically 5 to 30 micrometers depending on valve precision requirements. Manufacturing systems use these valves in applications ranging from simple on-off control to proportional positioning with sub-millimeter accuracy.

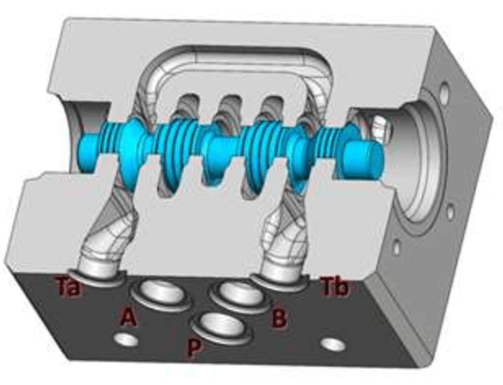

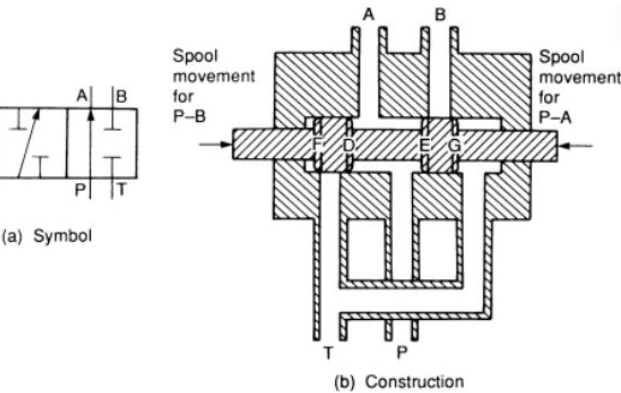

The spool’s cylindrical body features raised sections called “lands” separated by recessed areas called “grooves” or “annular spaces.” The function of the spool is to move within the sealed case and provide the function of either blocking or opening ports depending on the position of the spool. As the spool translates axially inside the valve body, lands align with or block ports drilled through the housing.

Consider a basic 4-way, 3-position valve operating a double-acting cylinder. In the neutral position, the spool’s lands block all four ports—P (pump), T (tank), A (cylinder extend), and B (cylinder retract)—maintaining pressure and holding the load. When the solenoid is energized, the valve shifts to opposite position, and pressure goes straight up to the A work port while the B work port connects to tank. This causes the cylinder to extend. Reversing the solenoid polarity shifts the spool oppositely, routing pressure to port B and draining A to tank, retracting the cylinder.

The lands create seal interfaces against the bore without requiring additional O-rings in many designs. This metal-to-metal sealing with controlled clearance allows for reliable operation under high pressures—commonly 3,000 to 5,000 PSI in industrial systems, with some reaching 10,000 PSI in specialized applications. The clearance must be tight enough to minimize internal leakage while allowing smooth spool movement without binding.

Spool nomenclature follows a systematic convention. Spool valves are referred to by nomenclature such as 3/2 or 5/3, where the first number relates to the number of ports and the second to the number of different spool positions. A 4/3 valve has four ports and three possible spool positions. This standardization enables engineers to specify valve functions precisely across different manufacturers and applications.

Pressure and velocity relationships inside the valve determine system response and energy efficiency. When fluid flows from the high-pressure pump port through the spool’s open pathways to a work port, it encounters sudden area changes that create pressure drops and turbulence. The flow regime transitions from laminar in narrow clearances to turbulent in larger chambers.

Research shows that thermal deformation of the spool is the main factor leading to failure of hydraulic spool valves, with temperature differences reaching 47.5°C or higher between the spool and valve body. This occurs because high-velocity fluid flow creates viscous friction heating. For a valve with 20mm diameter and 7-20 μm clearance, thermal expansion can consume the entire clearance gap when temperature rises from 25°C to 120°C, causing the spool to bind.

Flow rate through the valve depends on the orifice area created between spool lands and ports. The relationship follows the orifice equation: Q = Cd × A × √(2ΔP/ρ), where Q is flow rate, Cd is discharge coefficient (typically 0.6-0.7 for spool valves), A is orifice area, ΔP is pressure drop, and ρ is fluid density. A valve rated for 21 GPM at 3,000 PSI must maintain sufficient orifice area across its stroke to achieve this flow without excessive pressure loss.

Reynolds number calculations determine whether flow remains laminar (Re < 2,300) or becomes turbulent (Re > 4,000) in the annular clearance. For hydraulic oil with kinematic viscosity of 32 cSt flowing at 2 m/s through a 15 μm clearance, Re ≈ 940, indicating laminar flow. However, at port openings where velocity increases, flow transitions to turbulence, generating heat and noise.

Port arrangements define the valve’s functional capabilities. Different configurations such as open-center, closed-center, tandem center, float, and regenerative spools provide specific operational benefits for energy efficiency, speed control, or load management.

Closed-center configuration blocks all ports in neutral position, maintaining system pressure and enabling multiple valves to operate from a single pump without pressure loss. This arrangement suits applications requiring independent control of multiple actuators.

Open-center configuration allows fluid to flow freely from the pump to the reservoir in the neutral position, enabling continuous circulation. This design unloads the pump when no work is being performed, reducing heat generation and energy consumption. Mobile equipment commonly uses this configuration.

Tandem-center spools connect the pump port to tank in neutral while blocking work ports. This unloads the pump while maintaining actuator position. The configuration serves applications requiring frequent idle periods between operations.

Float spools connect all ports together in one position, allowing external forces to move the actuator freely. Mower decks on tractors use this configuration to follow ground contours. The hydraulic cylinder neither extends nor retracts under pressure but moves passively in response to terrain.

| Configuration | Pump in Neutral | Work Ports | Applications | Energy Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Closed-center | Pressurized | Blocked | Multiple actuators | Moderate |

| Open-center | To tank | Various | Mobile equipment | High |

| Tandem-center | To tank | Blocked | Frequent idle | High |

| Float | Connected | Connected | Passive following | N/A |

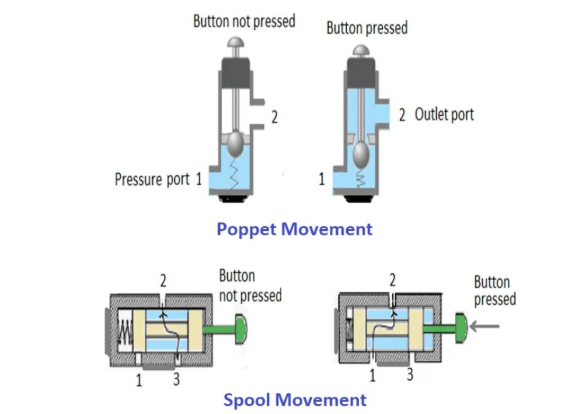

The mechanism that moves the spool determines system performance and control precision. Most spool valves use input power of either electricity through solenoid valves or mechanical motion like a lever arm or joystick.

Solenoid actuation employs electromagnetic force to push or pull the spool. When current flows through the coil, it generates a magnetic field that attracts a ferromagnetic plunger connected to the spool. A solenoid can exert a pull or push of about 5-10 kg, which is adequate for most pneumatic spool valves but too low for direct operation of large-capacity hydraulic valves. Response times range from 20 to 100 milliseconds depending on valve size and operating pressure.

Manual actuation through levers or joysticks gives operators direct tactile feedback and proportional control. The force required depends on spool friction and spring return forces. Well-designed manual valves require 2-5 kg of lever force for comfortable operation. Detent mechanisms can lock the spool in specific positions for hands-free operation.

Pilot actuation uses a small solenoid valve to control hydraulic pressure that moves the main spool. This indirect method enables small electrical signals to control large flow capacities. A 24V solenoid drawing 2 watts can pilot a valve handling 50 GPM at 5,000 PSI. The trade-off is slightly slower response—typically 100-200 milliseconds—due to the two-stage operation.

Proportional solenoids provide variable force output based on input current, enabling precise spool positioning. These systems achieve positioning accuracy within ±0.1mm and flow control to ±2% of maximum. Closed-loop feedback from position sensors further improves accuracy. Industrial robots and automated manufacturing systems rely on this precision.

Selecting the appropriate valve requires matching its characteristics to system requirements. Flow capacity must exceed maximum demand with margin for pressure drop. A hydraulic cylinder with 4-inch bore moving at 12 inches per second requires approximately 10 GPM. Specifying an 11 GPM valve provides suitable capacity with reasonable pressure loss.

Choosing the correct spool configuration ensures that hydraulic systems operate efficiently and reliably, as a mismatch can lead to performance issues such as overheating, slow response, or pressure instability. System analysis should consider duty cycle, load characteristics, and environmental conditions.

Contamination management proves critical for valve longevity. The radial clearance between spool and bore in directional control valves ranges between 3 and 13 microns, and if these clearances become invaded by hard particles (silt) or soft particles (varnish and sludge), more force is required to move the spool. Filtration to 10 microns absolute prevents most contamination-related failures. Systems should incorporate filtration on both return lines and downstream of the pump.

Temperature management addresses thermal expansion concerns. Maintaining fluid temperature below 60°C (140°F) minimizes viscosity changes and thermal distortion. Oversized reservoirs, heat exchangers, and proper duty cycling help control operating temperature. System designers should calculate heat generation from pressure drops and mechanical friction to size cooling capacity adequately.

Pressure transient management protects valve components. Rapid directional changes or sudden stops create pressure spikes that can damage seals or cause hydraulic shock. Implementing cushioning in cylinders, adjusting valve switching speeds, and installing accumulators dampens these transients.

Pressurized fluid enters through the pump port when the spool shifts position. The spool’s movement aligns internal passages—created by the spaces between lands—with specific ports drilled through the valve housing. This alignment creates open flow paths from the pressure source to work ports. Fluid flows from high pressure zones to lower pressure zones through these opened passages while blocked ports prevent backflow or cross-contamination between circuits.

Contamination is the primary cause, as hard particles like silt or soft particles like varnish and sludge invade the tight clearances between spool and bore. The radial clearance of just 3-13 microns leaves little room for particulates. Thermal deformation from viscous heating compounds the problem by expanding the spool while the housing remains cooler. Inadequate filtration, water contamination, and operating above recommended temperatures accelerate these failure modes.

A single valve cannot simultaneously control multiple cylinders independently. However, multi-spool valve assemblies—called valve banks or stacks—incorporate several spool sections in one housing. Each spool controls one cylinder or motor. The pump supplies all sections, and each has independent actuation. Common configurations range from 2 to 6 spools. This modular design reduces piping complexity and improves installation efficiency compared to individual valves.

Two-position spools have only actuated and rest states—typically energized and de-energized for solenoid valves. Three-position spools add a center position, usually maintained by centering springs when no actuation occurs. The center position can block all ports (closed-center), connect pump to tank (tandem-center), or interconnect all ports (open-center). Three-position designs enable holding loads, neutral idling, or floating, depending on the center configuration chosen.

Calculate the cylinder’s flow requirement using: Q = (A × V) / 231, where Q is GPM, A is piston area in square inches, and V is desired velocity in inches per second. For a 4-inch bore cylinder (12.57 sq in area) moving at 10 in/sec: Q = (12.57 × 10) / 231 = 0.54 GPM per cylinder port. Account for both extend and retract sides, add 20-30% margin for pressure drop and future needs, and verify the valve’s pressure rating exceeds system maximum.

Regular maintenance includes monitoring hydraulic fluid condition with laboratory analysis every 500-1,000 operating hours, changing filters per manufacturer schedules or when differential pressure indicators signal restriction, checking for external leaks at housing joints and port connections, and verifying actuation response times remain within specifications. Internal wear typically manifests as slower response, internal leakage causing drift under load, or increased operating temperature. Most valves require rebuild or replacement rather than field repair when internal components degrade.

The spool’s precision movement within micron-scale clearances transforms system pressure into controlled mechanical work. Engineers and technicians who understand the fluid dynamics, thermal considerations, and configuration options can specify systems that deliver reliable performance across demanding applications. As industrial systems push toward higher pressures, faster response times, and greater efficiency, the fundamental principles of spool valve operation remain the foundation for hydraulic power transmission.