Menu

Industrial systems operating beyond standard shifts face a sobering reality: valve-related failures account for 35% of unplanned downtime in continuous-operation facilities, with thermal-induced spool malfunction representing the single largest contributor. The global spool valves market, valued at $2.5 billion in 2025 and growing at 6% annually through 2033, reflects increasing recognition that valve reliability directly determines system uptime in manufacturing, construction equipment, and automated production lines where 24/7 operation is non-negotiable.

Spool valves function as the central switching mechanism in fluid power systems, controlling directional flow and pressure distribution across hydraulic and pneumatic circuits. In extended-runtime environments—manufacturing plants, mobile heavy equipment, automated warehouses—these directional control components regulate actuator movements that can number in the millions per year. A single valve failure cascades through interconnected systems: halted production lines, immobilized equipment, or safety shutdowns that can cost $22,000 per hour in lost productivity according to 2024 manufacturing data.

The mechanics of continuous operation expose fundamental design constraints. Unlike electrical switches that experience minimal degradation from repeated cycling, spool valves operate within 3 to 13-micron radial clearances where thermal expansion, fluid contamination, and mechanical wear interact continuously. Systems designed for intermittent use—8-hour shifts with cooling periods—perform differently when subjected to uninterrupted 168-hour work cycles. Temperature stabilization becomes critical; operating fluid temperatures in continuous systems typically range 50-70°C, but localized heating around throttling points can exceed 120°C.

Proper valve selection and maintenance protocols separate reliable systems from those prone to unexpected failure. Industrial surveys indicate facilities implementing structured spool valve monitoring reduce emergency maintenance events by 60%, while extending component service life from 18 months to 36+ months. The difference lies not in valve quality alone, but in understanding how extended operation amplifies specific failure mechanisms that remain dormant in intermittent-use scenarios.

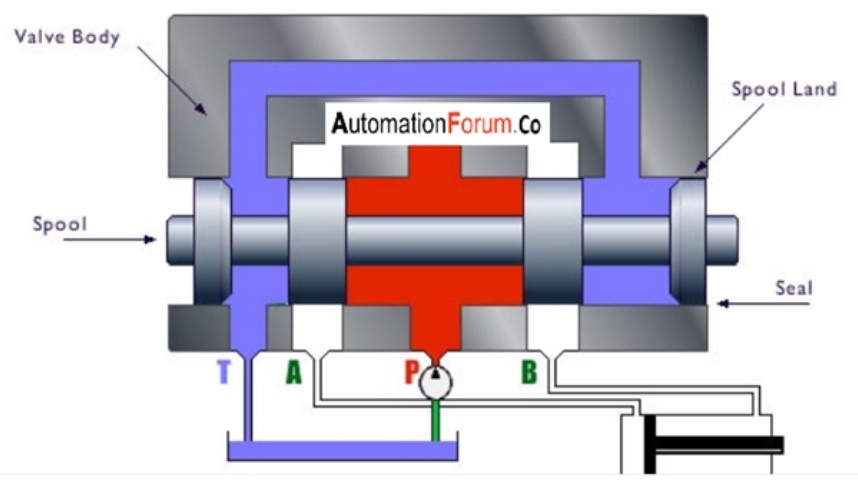

A spool valve consists of a precision-machined cylindrical shaft (the spool) sliding within a close-tolerance bore in the valve housing. Raised sections on the spool called “lands” block or connect internal passages to multiple ports—typically pressure inlet (P), tank return (T), and working ports (A, B) that connect to cylinders or motors. Movement of the spool redirects hydraulic fluid or compressed air between these ports, enabling control of actuator direction and speed.

The functional genius lies in the sliding interface. Radial clearances between spool and bore typically measure 0.003 to 0.013 millimeters—roughly one-tenth the diameter of a human hair. This precision enables rapid shifting (response times under 50 milliseconds for solenoid-actuated valves) while maintaining acceptable leakage rates. Internal leakage across closed ports, while unavoidable due to clearance gaps, should remain below 3% of rated flow in properly functioning valves. When clearances expand through wear or contamination, leakage increases exponentially, degrading system performance and generating excess heat.

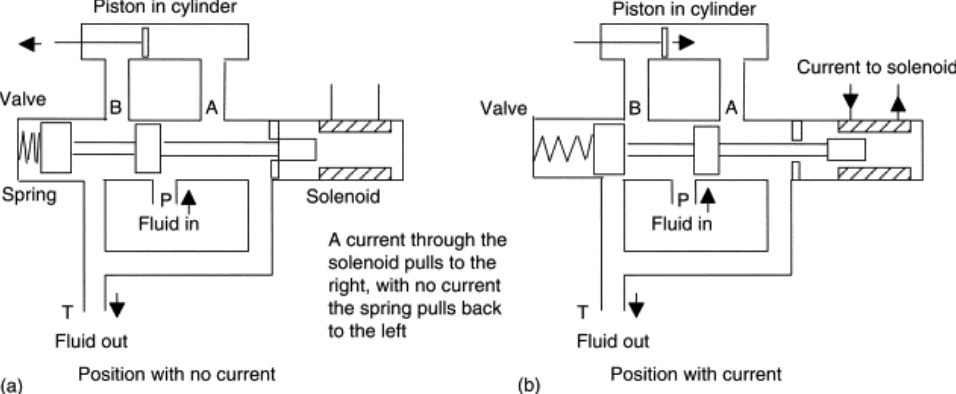

Actuation mechanisms vary by application requirements. Solenoid operators use electromagnetic coils to shift the spool; 24V DC solenoids dominate industrial controls due to standardized power supplies, though they consume 1.5-2.5 watts continuously when energized. Manual lever actuation provides direct operator control in mobile equipment. Hydraulic pilot operation uses system pressure to shift larger spools, reducing required input force. For high-precision applications, proportional valves employ variable-current solenoids enabling infinitely adjustable spool positions and corresponding flow modulation.

Valve configuration determines operational behavior. Two-position valves shift between two discrete states—extend/retract, on/off. Three-position valves add a neutral center where spool positioning affects system behavior: closed-center designs block all ports for load holding; open-center designs connect pump to tank for unloaded circulation; tandem-center partially opens paths for specific functions. Mobile hydraulic systems typically employ open-center configurations; industrial automation favors closed-center designs with variable-displacement pumps. Configuration mismatch causes system inefficiency or outright malfunction—a closed-center valve on a fixed-displacement pump generates continuous heating and pressure buildup.

Extended-runtime systems confront a thermal reality absent from intermittent operations: heat accumulates faster than dissipation capacity removes it. Research from Yan et al. (2024) demonstrates that in a 20mm diameter spool operating continuously at 3,000 PSI, thermal deformation of the spool can reach 20 microns while the valve bore expands 41 microns as temperatures rise from 25°C to 120°C. This differential expansion reduces effective clearance, increasing friction and eventually causing the phenomenon known as “thermal clamping.”

The physics involves material properties and heat generation sources. Throttling action at partially-open ports converts fluid pressure into heat through viscous friction. Spool and housing typically use different materials—hardened steel for spools, aluminum or cast iron for housings—each with distinct thermal expansion coefficients. Aluminum expands roughly twice as fast as steel per degree of temperature increase. Initially, this difference works favorably, expanding the bore faster than the spool. However, direct metal-to-metal contact at sliding surfaces, combined with restricted cooling in the bore interior, causes the spool temperature to exceed housing temperature by 30-50°C in sustained high-flow conditions.

Thermal clamping occurs when the temperature differential reverses—the spool becomes hotter than the housing. At this point, differential expansion works against clearance, progressively squeezing the spool. Eaton Hydraulics testing shows a spool reaching 95°C in a 25°C housing can generate 27.4 Newtons of clamping force, persisting for 19+ seconds. For solenoid valves, where the solenoid typically exerts only 44 Newtons (10 pounds-force), this represents significant resistance. AC solenoids face particular risk: if the clamped spool prevents full plunger travel, the coil remains in high-inrush current mode, generating heat that can cause insulation failure within minutes.

Mitigation strategies address heat generation and dissipation. Proper fluid selection matters—hydraulic oils with viscosity index >150 maintain stable viscosity across temperature ranges, reducing shear heating. Flow velocity limits prevent excessive throttling losses; keeping velocity below 7 meters/second through valve passages reduces localized heating. Heat exchangers or cooling jackets maintain fluid temperatures below 60°C in high-duty-cycle systems. For critical applications, valves with matched thermal expansion materials—all-steel construction or thermally-compensated designs—eliminate differential expansion issues, though at 40-60% cost premiums over standard configurations.

Directional control valves are specified using a numerical designation: ports/positions. A 4/3 valve has four ports and three spool positions. Common configurations include 3/2 (three ports, two positions) for single-acting cylinders; 4/2 for double-acting cylinder control; and 5/3 for precise three-position control with dedicated exhaust paths. The notation appears simple, but conceals critical operational differences determined by spool land geometry.

Center position configuration dramatically affects system behavior in neutral state. The “tandem center” connects pump to tank while blocking work ports—maintaining load position while unloading the pump. “Float center” connects work ports to tank while blocking pump—allowing external forces to move the actuator. “Regenerative center” connects one work port to both tank and pump—enabling rapid extension at reduced force. Selecting incorrect center configuration causes pressure spikes, unintended motion, or inability to hold loads. Power & Motion technical documentation emphasizes that closed-center spools operating with fixed-displacement pumps generate continuous heat even when no work is performed, as full pump flow passes through the valve at system pressure.

Spool type numbering (common in industrial valve systems) defines internal land configurations. Eaton-Vickers #2 spool represents standard directional control with blocked center; #0 spool relieves all ports to tank in center position; #6 spool connects both work ports to tank, used for motor control or when external load-holding valves are present. CrossCo technical bulletin warns that identical valve bodies accept different spools—external appearance provides no indication of internal function. Part number verification is mandatory; visual selection has caused equipment damage when mismatched spools were installed.

Material selection influences service life and operating limits. Stainless steel spools resist corrosion in mobile equipment and marine environments, tolerate higher temperatures, and maintain surface finish through extended service. Aluminum spools reduce weight and cost in lower-duty applications but are susceptible to galling and wear in contaminated systems. Hard-chrome plating on steel spools extends wear resistance and enables tighter manufacturing tolerances. Seal materials likewise vary: nitrile (NBR) seals handle petroleum oils to 100°C; fluorocarbon (FKM/Viton) tolerates 150°C and aggressive fluids; polyurethane provides superior wear resistance for high-cycle applications. Application environment dictates appropriate combinations—indoor manufacturing allows cost-optimized materials while mobile construction equipment requires environmental protection regardless of cost.

Spool valve degradation follows predictable patterns, with failure signatures appearing before complete malfunction. Internal leakage represents the most common progressive failure. As radial clearances increase through abrasive wear or seal degradation, flow bypasses intended paths. Symptoms include slow cylinder movement despite normal pump pressure, inability to maintain position under load, and elevated fluid temperature from continuous circulation through clearance gaps. Quantitative diagnosis involves comparing actual cylinder cycle times against baseline performance; a 30% speed reduction indicates significant internal leakage requiring intervention.

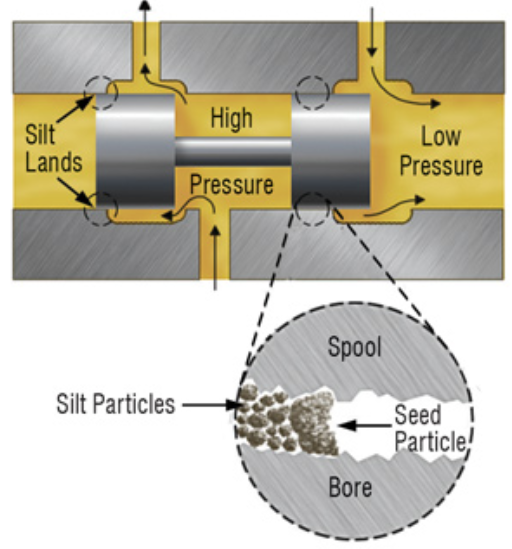

Contamination-induced binding occurs when particulates invade the spool-bore clearances. Silt—hard particles under 10 microns—progressively fills clearance gaps, increasing spool friction. Field data from contaminated systems shows that once clearances become invaded by particles, force required to shift the spool increases from normal 10-15 Newtons to 130+ Newtons—well beyond solenoid capacity. This condition, termed “silt-lock,” prevents spool movement entirely. Warning signs include sluggish response, intermittent failure to shift, and increased current draw in solenoid coils. The condition especially affects valves operated infrequently in contaminated environments, as static spools allow particle settlement.

Soft contamination—varnish deposits, oxidized oil residues, bacterial growth—creates different symptoms. Varnish buildup produces a sticky, adhesive coating on spool surfaces, causing stick-slip motion rather than smooth travel. Operators notice jerky actuator movement, chatter during operation, and initial resistance overcome by a sudden break-free. Varnish forms when oil operates at elevated temperatures (above 80°C) with inadequate antioxidant additives or extended service intervals. Bacterial contamination occurs in water-contaminated systems, producing sludge that combines with varnish to create particularly problematic deposits.

Seal failures manifest distinctly from mechanical wear. External leakage at port connections indicates gasket or O-ring degradation—typically from hardening due to heat exposure or chemical attack. Internal seal failures allow cross-port leakage while maintaining external integrity. Symptoms parallel those of clearance wear: slow motion, inability to hold pressure, elevated temperature. Differentiation requires pressure testing: blocking work ports and applying pressure reveals whether leakage occurs through seal paths or clearance gaps. Advanced diagnostics employ ultrasonic detection to identify leak points non-invasively.

Predictive maintenance programs monitor multiple indicators: fluid cleanliness (ISO 4406 codes), temperature profiles, response timing, power consumption. Establishing baseline performance when valves are new enables quantitative comparison. Trending over time reveals gradual degradation before functional failure. Systems reaching 60% of expected service life warrant closer monitoring; those showing 20% performance degradation require investigation. This structured approach reduces emergency failures by 70% compared to reactive maintenance, according to industrial maintenance surveys.

Continuous-operation systems require proactive contamination control as primary defense against valve failure. Filtration standards matter significantly: achieving ISO 16/14/11 cleanliness (particles >4μm, >6μm, >14μm per 100ml) extends spool valve life threefold compared to typical ISO 18/16/13 levels common in less-critical systems. Filter selection involves both micron rating and dirt-holding capacity; 10-micron absolute filtration captures particles small enough to invade spool clearances, while beta ratios >200 ensure capture efficiency. Filters require sizing to handle full system flow without excessive pressure drop; 3-5 PSI maximum drop is standard practice.

Fluid temperature management extends component life and maintains viscosity within optimal ranges. Heat exchangers should maintain reservoir temperature below 60°C; systems consistently operating above 70°C experience doubled oxidation rates and accelerated seal degradation. Temperature monitoring at multiple points—reservoir, valve manifolds, return lines—identifies localized heating issues before they cause damage. Thermographic imaging during operation reveals hot spots indicating restricted flow, excessive leakage, or insufficient heat dissipation.

Scheduled fluid analysis provides early failure detection. Testing intervals vary by criticality: quarterly analysis suits most industrial systems, while monthly testing applies to high-value continuous operations. Key parameters include viscosity (degradation indicates thermal or oxidative damage), particle count (trending reveals filter effectiveness), acid number (oxidation indicator), and water content (seal and corrosion threats). Fluid replacement follows condition-based rather than calendar-based intervals; fluid maintaining specification parameters can operate safely beyond typical 1-2 year change intervals.

Valve disassembly and inspection follows when performance degradation or contamination events occur. Inspection includes visual examination for wear patterns, scoring, or corrosion; dimensional measurement of critical clearances using micrometers or air gauging; and seal evaluation for hardness, compression set, or surface cracking. Minor scoring on spool lands can be polished; deeper grooves require spool replacement. Bores showing wear beyond 0.005mm increase from specification warrant valve body replacement. Complete seal replacement during disassembly is standard practice; reusing seals risks premature failure.

Rebuild vs. replacement decisions depend on extent of wear and cost factors. High-quality manifold-mounted valves with expensive machined bodies justify rebuilding when only seals and spools require replacement—typically 30-40% of new valve cost. Inexpensive line-mounted valves often cost less to replace than rebuild. Age matters; valves approaching 10-15 years develop fatigue issues and outdated sealing technology, making replacement more economical despite superficial functionality. Maintaining spare valve inventory for critical stations enables rapid replacement during scheduled maintenance, minimizing downtime while worn units undergo shop refurbishment.

Standard industrial spool valves are designed for continuous operation when properly sized, maintained, and thermally managed. Units running at 60-80% of rated flow capacity with adequate cooling reliably operate 168-hour weeks. Critical factors include fluid temperature below 60°C, contamination levels under ISO 16/14/11, and proper center position configuration to avoid unnecessary heat generation during idle periods.

Inspection intervals depend on contamination control quality and duty cycle severity. Systems with effective filtration (beta >200, 10-micron rating) and stable temperatures warrant 6-month valve inspections and annual rebuilds. Harsh environments with mobile equipment or poor contamination control require 3-month inspections. Condition monitoring through fluid analysis and performance testing enables interval adjustment based on actual wear rather than arbitrary schedules.

Prevention strategies include: maintaining fluid temperature below 60°C through adequate heat exchange capacity, specifying valves with matched thermal expansion materials (all-steel construction), limiting flow velocity to reduce throttling losses, and selecting valve sizes that operate at 60-70% of maximum rated flow. For critical applications, pilot-operated valves move larger spools using hydraulic force, overcoming thermal-induced friction that would stall smaller solenoids.

Replacement makes sense when bore wear exceeds manufacturing tolerance by >0.005mm (indicating loss of sealing efficiency), when valve age approaches 15 years (seal technology and fatigue issues), when multiple rebuild cycles have been performed (diminishing returns), or when valve cost is less than 3x the rebuild expense. High-value manifold-mounted valves with minor wear justify rebuilding; line-mounted cartridge valves generally favor replacement.

Spool valves offer balanced forces during operation, multi-position control, and straightforward flow path switching—ideal for directional control. However, they inherently leak small amounts across closed ports due to clearance gaps. Poppet valves provide zero leakage when closed and faster response times, but face unbalanced forces requiring stronger operators and typically offer only two-position control. Application determines optimal choice: position holding favors poppets; directional control with multiple positions favors spools.

Cylinder drift under load when the spool is in neutral position results from internal leakage through spool-bore clearances. Even with all ports theoretically blocked, 3-13 micron radial clearances allow hydraulic fluid migration. Pressure on the work port side gradually equalizes with tank pressure, allowing the load to move. Solutions include: external load-holding check valves that mechanically seal work ports, counterbalance valves that oppose cylinder movement, or switching to poppet-type directional control that provides zero-leakage sealing when closed.

Schema Suggestion:

Visual Elements Recommended:

Internal Link Opportunities: