Menu

All solids, when deformed by external forces, tend to restore their original shape, i.e., they produce an elastic force opposing the external force. Springs are no exception. Because the deformation-elastic force characteristics of springs are relatively easy to design and control, they are widely used in hydraulic valves. Hydraulic valves without springs are extremely rare, limited to a few shuttle valves and manual shut-off valves, etc. For hydraulic valves, spring force is both an intentionally designed control force and can also become an unwelcome resistance. Hence, spring force is not a free favor.

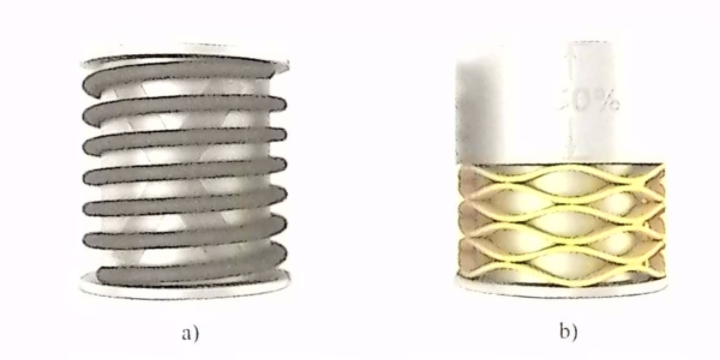

Stamped spring washers are made from corrugated steel strips. Since multiple elastic elements deform simultaneously under compression, the original length can be reduced to only 50% of that of a wire spring with the same stiffness. Currently, almost all springs used in hydraulic valves are cylindrical compression springs made of steel wire. Conical springs and disc springs are rarely used, so the following analysis focuses on cylindrical steel wire compression springs.

Cylindrical compression springs generally satisfy Hooke’s Law: spring force is proportional to compression, i.e.:

F = GS

Where:

Spring stiffness is proportional to the shear modulus of the spring wire material and the fourth power of the wire diameter, and inversely proportional to the third power of the mean coil diameter and the number of active coils. The shear moduli of different materials for commercially available springs are similar; the main differences lie in corrosion resistance. For estimation of compression spring force, refer to the estimation software “Hydraulic Valve Estimation 2023” included with this book.

What actually occurs in a steel wire compression spring under compression is the twisting of the wire, and the torsional deformation of the wire has a certain limit. Exceeding this limit causes permanent deformation — loss of elasticity, or even fracture. Therefore, steel wire compression springs have a maximum compression limit. Compression frequency also affects this limit: the higher the compression frequency, the shorter the service life.

During the manufacturing process of springs, the steel wire must be coiled, which produces fine cracks on the surface. When working submerged in oil with varying pressure, a phenomenon similar to rock weathering occurs: pressurized oil enters the cracks, and when external pressure drops, it expands, enlarging the cracks, causing the surface layer of the wire to peel off and shortening service life. Therefore, hydraulic springs must undergo a shot peening process to remove the cracked surface layer.

Steel wire develops internal stress after coiling, making the spring prone to deformation during initial use. Therefore, springs need to undergo stress-relief heat treatment.

If the actual gap between coils (S-d) is less than the wire diameter d, the spring wire can be prevented from interlocking if it happens to break, which would cause a sudden significant drop in spring force.

The force transmitted by a wire spring is asymmetric about its axis, so both ends of compression springs must be closed and ground flat for at least 1.5 coils (called inactive coils), ensuring that the force transmitted to the spool is not from a single point but uniformly distributed around the entire circumference.

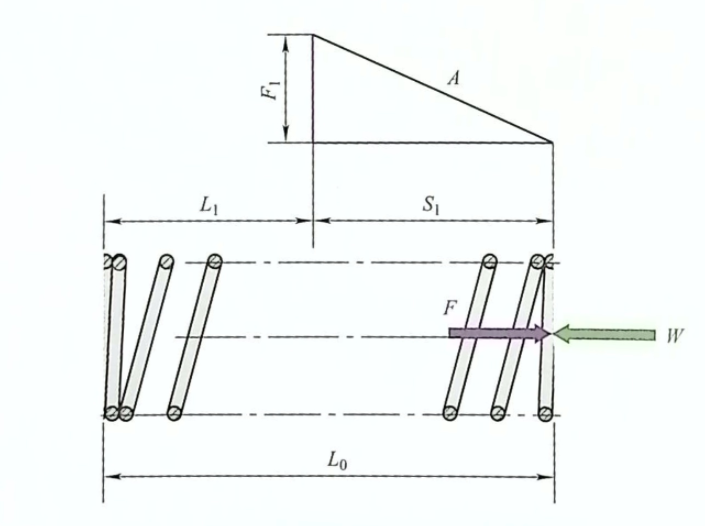

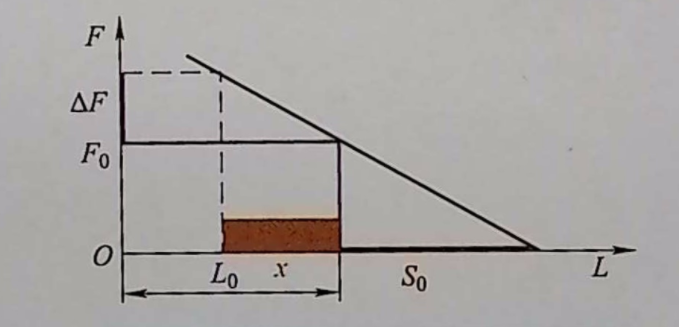

When a hydraulic valve is assembled, the spring is often already compressed to a certain degree; the spring force at this point is called preload force. In hydraulic technology, the quotient of spring force and the opposing hydraulic effective area (simply called spring pressure) is frequently used; the quotient of preload force and the opposing hydraulic effective area is called preload pressure.

Springs have the following applications in hydraulic valves:

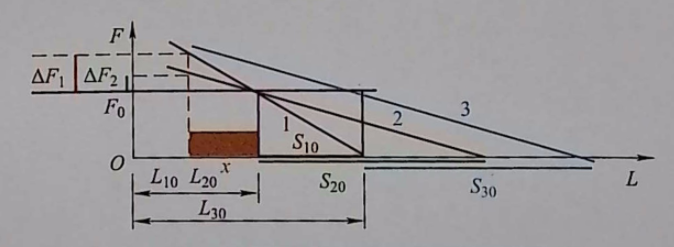

According to application requirements, preloading the spring provides a preload pressure that serves as the set pressure, such as setting the cracking pressure of a relief valve. To ensure a certain degree of versatility, many valves have a considerable adjustment range for preload.

What cannot be ignored is that during operation, the spool needs to move, so the spring force will inevitably change, and the spring pressure will also change. Therefore, strictly speaking, the spring force is not a constant value during operation. This is one of the reasons why the control pressure of a relief valve is not equal to its cracking pressure.

Using a softer spring can reduce the change in spring force, but the pre-compression must also be increased accordingly. To reduce stress in the spring during compression and ensure service life, sometimes a spring with a longer initial length must be selected, which remains relatively long after preloading. This is why some valves have particularly long tail sections.

For continuously adjustable valves, a softer spring means the spring force changes more slowly and gently with spool travel, making fine adjustment easier to achieve.

Many spools need to return to their initial position by spring force after oil pressure drops. For example, a check valve: when pressure at port ② is higher than port ①, the spool is pushed open to open the flow path; but when pressure at port ② drops, spring force is needed to overcome possible friction and other resistance to return to the initial position. In this case, the greater the spring force, the more reliable the return and the shorter the time required. Greater spring force means greater seating force, which usually reduces leakage.

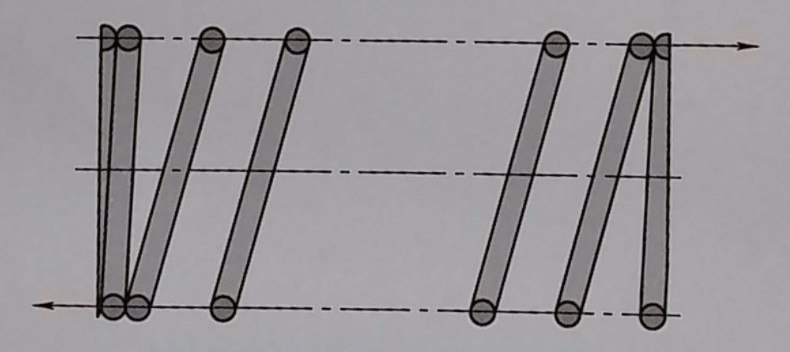

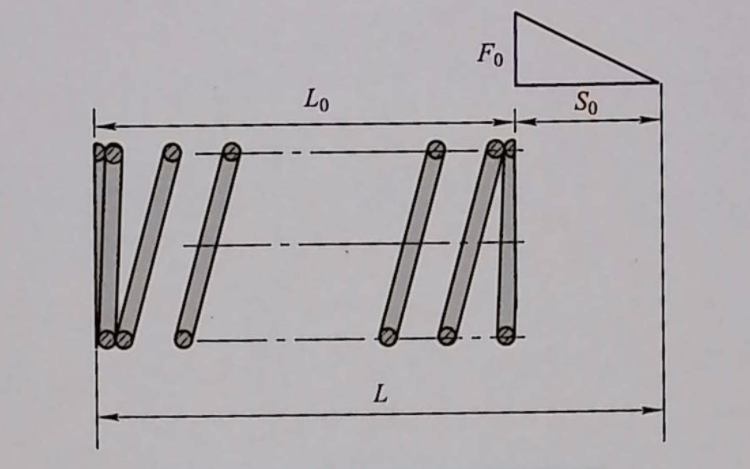

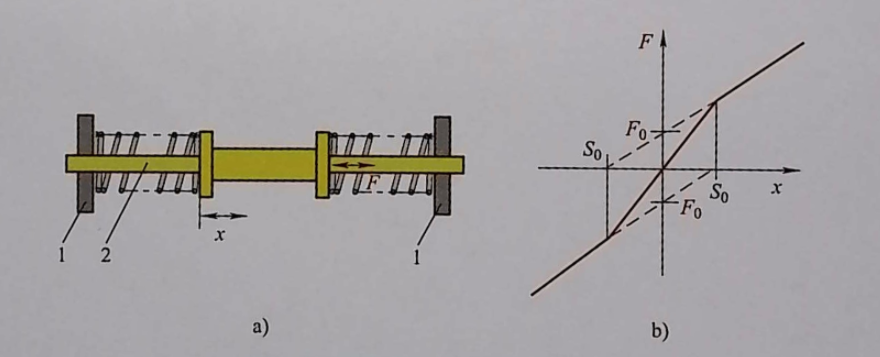

Using two identical springs with the same pre-compression, the equal preload forces obtained keep the spool at the center position — the position where preload forces are balanced. With a slight external force, the spool will move, and the spring forces acting on the spool will change rapidly, because while one spring is being compressed, the other is being released. After exceeding the preload range, only one spring is working.

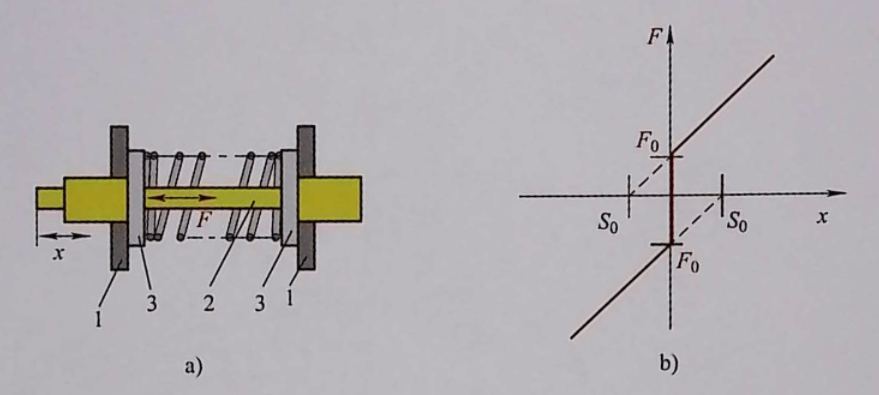

Centering can also be achieved with a single spring, but this structure has different displacement-spring force characteristics: when the operating force is less than the spring preload force, the spool will not move.

Using a spring, force can be converted to displacement. For example, springs are used in electro-proportional throttle valves: what the proportional solenoid can regulate through current is only force, while what the throttle valve needs to regulate is spool displacement. Using the compression-spring force characteristics of the spring, the electromagnetic force output by the solenoid can be proportionally converted to displacement.