Menu

As mentioned, the valve spool is something that only recognizes force, and the force exerted by oil when relatively stationary is pressure multiplied by the effective working area. Modern hydraulic working pressures often reach above 20MPa, which means that a pressure area of 1cm² will be subjected to a force greater than 2000N. Therefore, first consideration must be given to how to balance it to avoid it becoming resistance, and then to how to utilize it to make it an auxiliary force. This requires both proper handling of pressure and proper arrangement of the effective working area. This seems simple, but when the valve structure is relatively complex, it is not so obvious. The following provides explanations through some practical examples.

During operation, valve spools generally need to move axially (rotary valves are exceptions). Poppet valves utilize axial channels, therefore, the pressure and effective working area on both sides of the valve spool are often different, which may cause resistance, and thus opening and closing often requires very large control forces. Spool valves utilize flow channels that are generally radial, but if the axial force of the oil on the valve spool is not balanced, it will still cause resistance to the spool’s movement. There are several situations as follows.

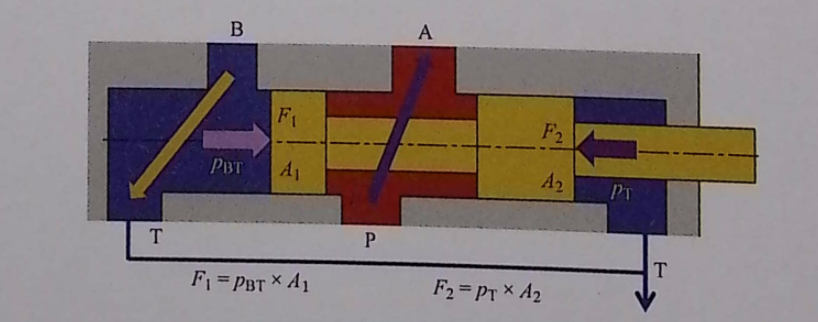

Although both the left and right chambers of the valve body connect to return port T, because the effective working area A₁ on the left side of the valve spool is greater than A₂ on the right side, if the pressure at port T is not zero, there will be a leftward force acting on the valve spool.

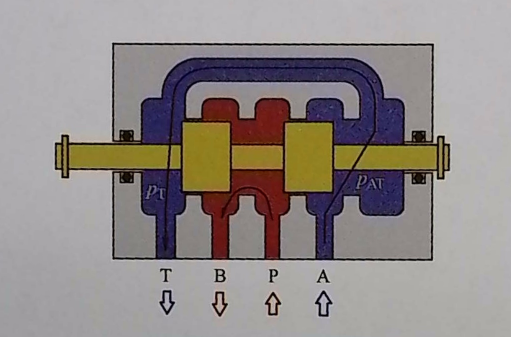

The so-called four-chamber valve has the same working area on both sides of the valve spool, but shares one T port. In this way, when oil flows back from port A, it must pass through the flow channel inside the valve body to reach port T, causing pressure drop, especially when the flow rate is large. Therefore, the return chamber pressure p_AT will be higher than p_T, creating a leftward pushing force on the valve spool.

For manual, mechanical, or ordinary solenoid valves, this is not a major problem due to the relatively large control forces. However, if it is an electro-proportional valve, the electromagnetic force is limited by current, especially for electro-proportional directional throttle valves, where the electromagnetic force needs to be converted into valve spool displacement through springs. If the electromagnetic force is partially offset by unbalanced hydraulic forces, the actual displacement of the valve spool will not reach the expected value.

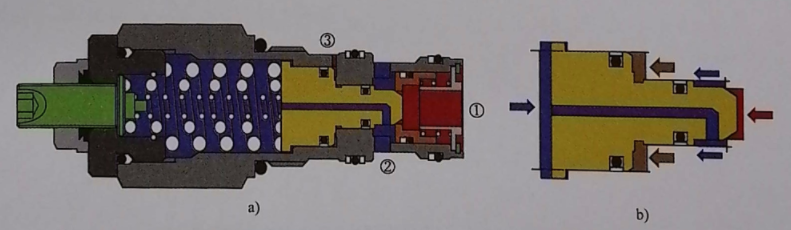

To solve this problem, the so-called five-chamber valve was developed: making the working area of each chamber on the valve spool the same. In this way, even if p_AT does not equal p_BT, their respective static pressures on the valve spool can still balance each other.

Static pressure is also positively utilized as auxiliary force, such as through area difference — differential action, pressure difference — differential pressure, superposition, etc., to achieve control of the valve spool. Static pressure is also a basic factor in forming damping to help reduce vibration.

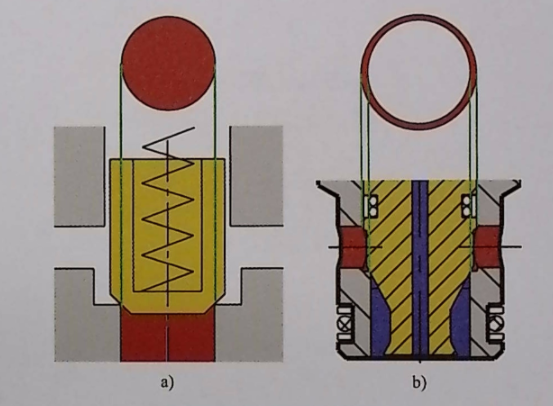

The valve spools of relief valves all need to withstand very high pressure. When used for small flow rates, the valve spool is small, and in direct opposition, the spring can still hold up. But when used for large flow rates, a larger valve spool is needed, and with direct opposition, a very strong spring is required, which is quite bulky. One method is to have the static pressure act only on the outer circle of the poppet valve spool, making the working area an annular shape, and the effective working area becomes much smaller. In this way, the acting force is reduced, and a bulky spring is no longer needed. This method is often called differential action.

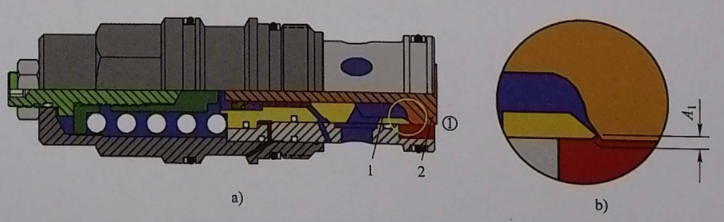

The load port ① of a counterbalance valve (circled numbers in the book’s illustrations, such as ①, ②, ③, etc., all indicate valve ports, and will not be explained one by one below) may have very high load pressure. The solution is: to have both the main valve spool and check valve spool contact surfaces be conical, but with different taper angles, so that the effective working area A₁ of the load pressure can be reduced to very small. Moreover, this effective working area is easily modified, thereby achieving different control ratios.

1) Single Small Orifice When outlet C of control chamber A is closed, the pressure on both sides of the valve spool is the same, and the spring preload presses the valve spool against the valve body, closing the flow channel.

If outlet C opens and connects to low pressure, oil will flow. When the liquid flow passes through differential pressure orifice B, there will be pressure drop, causing a pressure difference p₁−p_C on both sides of the valve spool. When the pressure difference multiplied by the working area exceeds the spring preload force, the valve spool can be pushed open, opening flow channel ①→②. In this example, the spring no longer needs to face high pressure p₁, but only the differential pressure p₁−p_C generated by the liquid flow through the small orifice, which is much easier.

Almost all pilot valves (pilot relief valves, pilot sequence valves, pilot pressure reducing valves), and in those cover plate-type cartridge valves with diameters of dozens or even hundreds of millimeters that can switch flow rates up to tens of thousands of L/min, all apply this principle.

The opening and closing of outlet C of the control chamber can be controlled directly by a solenoid valve, or controlled by a small (pilot) relief valve.

2) Double Small Orifice The main valve spool has two small orifices. Orifice B is larger than orifice A. Pilot valve spool 2 controls the opening and closing of orifice B.

When orifice B is closed, the pressure p₂ at port ② passes through connecting orifice A to control chamber C, making the pressure in control chamber C equal to p₂, which is higher than the pressure p₁ at port ①, thereby pressing the main valve spool against the valve body, and the main flow channel ②⇒① is blocked.

After the pilot valve spool opens orifice B, the oil from port ② will flow through orifice A to control chamber C, and then flow through orifice B to port ①. Because orifice B is larger than orifice A, the pressure p_C in the control chamber is close to p₁. The pressure p₂ at port ② acts on the outer ring of the main valve spool, lifting the main valve spool and opening flow channel ②⇒①.

1) Driving the Main Valve The control force needed for a large valve spool is generally also large. When the control force is insufficient, such as when manual or electromagnetic push cannot move the valve spool, a pilot control method is often adopted, using hydraulic actuation to push the main valve. At this time, the pilot valve and main valve can also be installed at a distance, called remote control. However, when adopting this installation method, consideration must be given to possible action delays caused by oil flow and pressure transmission.

2) Operating Multiple Valves Simultaneously An excavator operator needs both hands to simultaneously control four actions: boom, stick, bucket, and rotation. If ordinary sectional multi-way valves were used, there wouldn’t be enough hands. Using one hydraulic joystick that allows simultaneous X, Y direction actions enables single-hand control of two valves and two movements simultaneously.

3) Pressure Superposition The movement of the counterbalance valve’s main valve spool needs to be determined jointly by 3 pressures. If the valve spool is made in a stepped shape, introducing different pressures to different steps, then the total force of the oil on the valve spool is the sum of each pressure multiplied by its respective working area.

When the valve spool moves, the oil in the rear chamber needs an outlet. If obstructed or even completely sealed, the valve spool will be very difficult to move. Therefore, the rear chamber (spring chamber) is often connected to return oil, and some individual cases connect to atmosphere.

To slow down valve spool oscillation, some valves install a small orifice at the rear chamber outlet, making the rear chamber a damping chamber. When the valve spool is stationary, no liquid flow passes through the small orifice. When the valve spool moves and compresses the rear chamber, oil needs to pass through the small orifice, generating certain resistance, reducing the flow rate passing through, slowing down the valve spool’s movement, thereby reducing oscillation, so it is often called a damping orifice.

It should be noted: oil resists compression but not tension, damping action only occurs when oil is under pressure! When the valve spool moves in a certain direction, due to the throttling action of the damping orifice, the damping chamber pressure rises, which can obstruct the valve spool movement and exert damping action. However, if the valve spool moves quickly in the opposite direction, less oil returns to the damping chamber through the damping orifice, the pressure in the damping chamber will decrease, and may even form negative pressure. After that, when the valve spool moves in the original direction again, the damping action is reduced or even eliminated. To avoid this situation, a check valve can be installed to allow oil to enter the damping chamber smoothly.

Because the flow rate through the damping orifice is usually very small, in actual applications, damping orifices are made with relatively small diameters to provide cushioning effect, generally below 1.2mm. Plugs with damping orifices often have ready-made products available for purchase and are also convenient to replace. If machining yourself, you can first machine a larger hole in a hexagon socket plug, then machine out the required small damping orifice. To reduce the effect of oil viscosity, they are generally made as thin-walled orifices as much as possible.

Due to the small diameter, they are easily blocked by contamination particles. Therefore, in actual hydraulic systems, holes with diameters below 0.6mm are generally avoided. When unavoidable, two 0.6mm diameter holes are connected in series. Sometimes a small filter screen is added before the small orifice.