Menu

Two centuries. We’ve trusted this technology for two centuries.

It’s easy to ignore something that just… works. We’re all chasing the new, the digital, the “smart.” Big mistake. That unseen force building our cities, harvesting our food, and lifting us into the sky? That’s a principle from 1795.

Yes, hydraulics is over 200 years old. But to call it “old” is to completely misunderstand it.

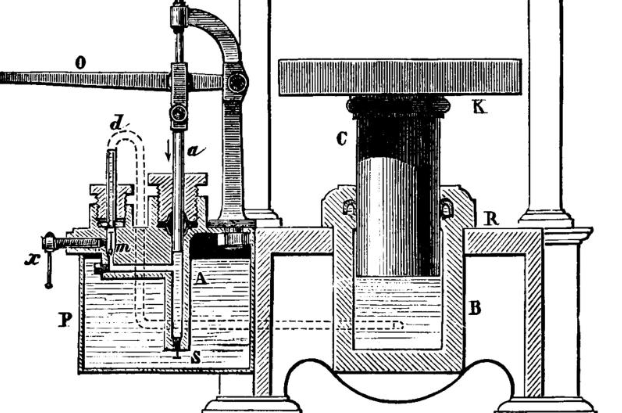

This is no relic. It’s a fundamental pillar of modern engineering, and it’s just as critical today as it was the day Joseph Bramah first patented his press.

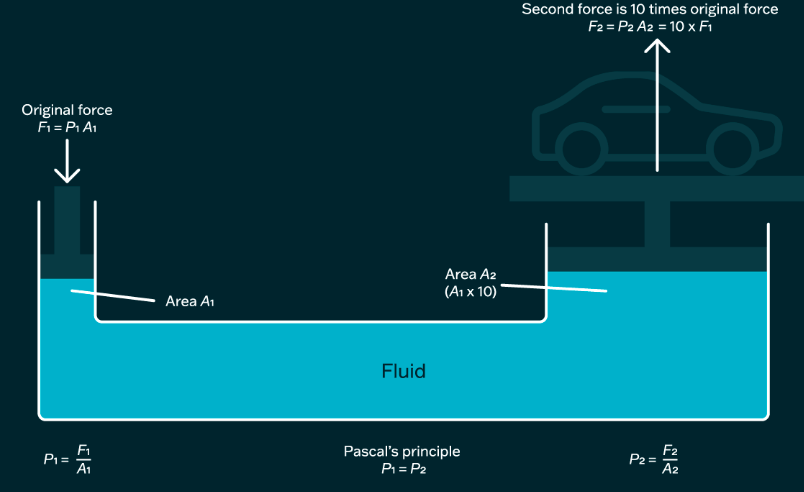

Bramah’s invention was pure physics. The essence of hydraulics is just Pascal’s Law. It’s deceptively simple: you push on a small bit of fluid, and that force gets transmitted, popping out as a massive force on a bigger bit. It’s the magic of turning a small, manageable push into a mountain-moving shove. That’s the trick.

But this 200-year journey wasn’t smooth. The medium itself had to change. Early hydraulics ran on water. “Hydro” means water. It was cheap, it was everywhere, and it powered the industrial revolution.

But water is a terrible medium. It freezes. It boils. It rusts everything it touches from the inside out and offers zero lubrication. The real leap, the one that built our world, came from modern hydraulics. And that means oil.

This was the game-changer. Suddenly, you had a fluid that could lubricate pumps, seals, and actuators. It doesn’t corrode. It can be engineered to handle insane temperatures, from the arctic to a steel mill. This shift from water to oil is what let hydraulics become the high-pressure, high-performance beast we know today.

So where does that leave hydraulics? In any complex system, you have the brains, the speed, and the muscle.

In our national economy, electronics and software are the brains. The hydraulics industry is the muscle. The “counterweight.”

It’s not flashy. It doesn’t move fast. But without that specific, heavy, stabilizing mass, the entire scale is worthless. You can’t weigh anything. You can’t measure anything accurately.

That’s hydraulics.

It’s the indispensable, heavy-lifting foundation that provides a power density—raw power in a small space—that electric motors and pneumatics can’t even touch.

When an 80-ton excavator needs to move a mountain of earth, that’s not a microchip doing the lifting. It’s a hydraulic ram. When a massive factory press stamps a car door from a sheet of steel, it is the uncompromising force of hydraulic fluid. When an A380 lowers its landing gear, it’s trusting hydraulics to take the load.

The industry isn’t the “engine” of the economy. It’s the critical enabler. It’s the boring, vital component that lets all the other, flashier parts do their jobs.

Given that 200-year-old principle, it’s easy to assume hydraulics is a “solved” technology. A dead end.

Not a chance. The old sword isn’t dull; hydraulic technology is still developing at a shocking pace. The innovation just isn’t in the principle anymore; it’s in the integration.

The big story is electro-hydraulics. We’re finally pairing hydraulic muscle with an electronic brain.

Forget simple, clumsy “on/off” levers. We now have proportional and servo valves that translate a tiny electrical signal from a computer into a perfectly controlled, immensely powerful movement. We’re talking about controlling position, speed, and force with micrometer-level precision.

And it’s getting smart. Old systems ran full-blast, all the time, just dumping excess energy as waste heat. A massive waste. Today’s “smart” systems use load-sensing pumps. They deliver only the exact pressure and flow needed for the task, right when it’s needed, and then idle. This slashes energy consumption.

We’re even embedding IoT sensors into valves and pumps to monitor pressure, temperature, and vibration. The system can now tell you it will fail in 300 hours, rather than just failing. This isn’t your grandfather’s technology. It’s silicon and steel fused together.

This evolution means the global market is flooded. You’ve got components from Germany, the US, Japan, and a rising tide of suppliers from Korea and China.

It’s dizzying. And it leads to the pragmatic debate you hear in every engineering shop: “Doesn’t matter if it’s an Eastern valve or a Western valve; a good valve is one that meets the application’s needs.”

This isn’t just a catchy phrase. It’s the core philosophy of good system design.

For the engineer on the factory floor, the flag on the box is secondary to the spec sheet and the reliability data. Does it solve the problem? That’s the only question that matters.

Is the application a critical flight-control surface on a fighter jet? Then the “best” valve is the one with a documented failure rate of one in a billion, regardless of cost. Is it a simple hydraulic log-splitter for consumer use? Then the “best” valve is the one that’s safe, reliable enough for a low duty cycle, and hits the price point.

The real debate isn’t “East vs. West.” It’s about Total Cost of Ownership (TCO). A cheap valve that fails and shuts down your whole production line is the most expensive part you’ll ever buy.

A good integrator isn’t loyal to a brand or a country. They are loyal to the application.

From Bramah’s water press to today’s data-driven, oil-powered systems, the tech has never stopped evolving. Its essence remains the same—pure, multiplied force. But its intelligence and efficiency are always being sharpened. As long as we need to move heavy things with power and precision, this 200-year-old “relic” will be doing the work.