Menu

As mentioned earlier, most performance characteristics of hydraulic valves need to be expressed using at least two-dimensional curves, such as the valve’s pressure differential-flow characteristics, proportional solenoid’s current-electromagnetic force characteristics, etc. Performance curves in product manuals should all come from testing. Testing of the hydraulic performance of hydraulic valves generally cannot be conducted independently, but needs to be carried out in a hydraulic circuit. Therefore, it is actually testing a hydraulic system, except that the test target at this time is the characteristics of the valve being tested. In this case, the test results also need to be expressed using curves.

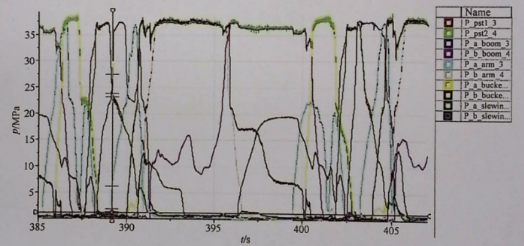

The transient response of component systems is often a curve with time as the horizontal axis. To evaluate the applicability of valves to actual applications, it is also necessary to test the actual hydraulic system and judge based on a pile of test curves. Changes in relevant parameters during the operation process of the main machine are also expressed in the form of test curves. Therefore, test curves are the most important form of expression in hydraulic technology. From test curves, many characteristics of the component system being tested can be understood; if you can read them, they can provide a solid basis for improvement.

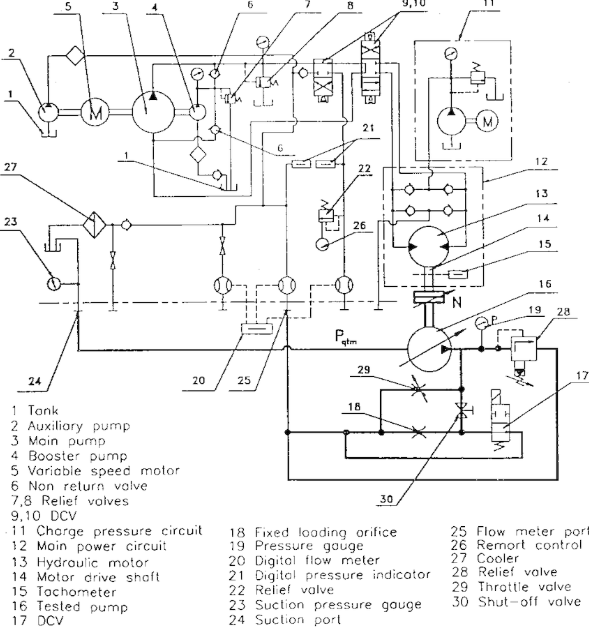

A German engineer selected matching pumps, motors and valves based on the parameters of an excavator designed by the main machine manufacturer and provided them to the main machine manufacturer. After the main machine manufacturer assembled and test-ran the machine, measuring pressure changes at designated points, he adjusted and optimized the hydraulic components they provided based on these test curves from thousands of miles away. Because test curves comprehensively reflect almost all the real information of the system being tested, they are often very complex and not easy to read, requiring meticulous and comprehensive preparatory work.

Before conducting hydraulic testing, in addition to learning and mastering some basic testing theories and terminology, working principles of hydraulic components and systems, relevant standards, and learning and mastering relevant testing instruments, preparations should also be made from the following aspects (see reference [13] for details).

Generally includes the following steps.

Pre-estimating the performance of hydraulic systems is an ability that hydraulic system designers must possess. Based on existing theory and experience, referring to similar products, pre-estimate as much as possible the form of test curves that may be obtained before conducting actual measurements. This is very beneficial for improving understanding of the component being tested and for test preparation. At the same time, it is also beneficial for promptly discovering abnormal measurement values in the measurement results caused by negligence during the test process. Just as guessing riddles helps you improve your intelligence, pre-estimation is also very helpful in strengthening your logical reasoning ability and deepening your hydraulic professional practice, helping you become a true insider.

For testing, the more fully the preparatory work is done, the more smoothly it will proceed, so-called getting twice the result with half the effort. Tests that start rashly and hastily often end in failure: a large pile of data is measured, but no needed results can be analyzed. The ancestral teaching: sharpening the axe will not delay the chopping of wood, indeed. Therefore, preparation is the key to testing success. The process of preparing for testing is also a process of improving research and development capabilities.

The “Tao Te Ching” says, “Difficult things in the world must be done from the easy; great things in the world must be done from the detailed.” Utilize existing conditions as much as possible, starting from the simple.

The actual working environment at the field site is generally worse than the laboratory: it may be outdoors, or there may be wind, sand and mud; or the environment is dangerous, requiring more cautious safety measures. Sometimes the test site is far from one’s own work unit, falling into poor communication, isolated and helpless, or with little help, which is also common. The cost of field testing is high, and the time available for testing is often limited, and some working conditions are not easy to reproduce. Therefore, try to first learn and attempt in your own unit’s laboratory on your own test bench: instruments, methods, test processes. After having certain capabilities, if possible, refer to actual applications and conduct testing in the laboratory that is close to actual working conditions, such as loading.

See the great in the small, a drop of water can reflect the sun’s rays. Starting from simple hydraulic circuits, one can also gain profound understanding of hydraulic systems. First try to test single actions, simple working conditions, and test them separately, so that the resulting test curves are relatively easy to understand. When studying test curves, also go from simple to complex, steady state first then transient state, and discuss non-urgent matters later. The purpose of testing, in the final analysis, is not for a large pile of data and curves, but to analyze the valve’s characteristics from them. Therefore, it is very important to make efforts to read (organize and analyze) test curves. Only by striving to analyze test results – curves, can you deepen your hydraulic practice. The depth of hydraulic practice does not lie in how many formulas you know, but in your ability to analyze test curves. Only by being able to read every section of the curve can you be considered to have reached the high realm of hydraulic practice.

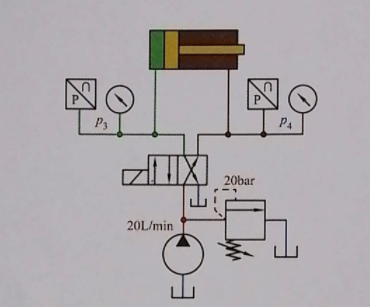

A simple hydraulic circuit is as follows:

Set up pressure sensors at the inlet and outlet of the hydraulic cylinder to record pressures p3 and p4.

Repeatedly energize and de-energize the directional control valve to make the piston rod extend and retract, complete the full stroke, measure and record the change status of pressures p3 and p4.

Steady-state analysis. First set aside the pressure spikes and concentrate on analyzing the steady-state processes where pressure changes are not large one by one. From this, identify, for example: — Which stages of the curve correspond to the extension and retraction processes? After identification, they can be directly annotated on the curve (1— Extension 2— Retraction A— Hydraulic cylinder starting impact B— Relief valve opening spike C— Pressure impact during directional valve switching). — The different working pressures and back pressures in these stages caused by different effective action areas of the two chambers. — Why is the pressure in each section so high? What factors determine it? Does it match the pre-estimation? — How long do these stages last? What factors determine them? Can they match the pre-estimation? Through analysis, it can also be found that the marked 20bar is actually not the opening pressure of the relief valve, but the control pressure when passing a flow rate of 20L/min.

Transient analysis. Analyze each pressure spike, what caused it? Can it be reduced? For example: — Pressure spikes caused by the inertia of the piston and piston rod due to sudden flow changes when the hydraulic cylinder starts; — Pressure spikes caused by delayed opening of the relief valve when the piston movement reaches the end of the stroke.

Through testing, the actual situation of component systems can be understood, with many benefits!

After arriving in Germany in 1988, the author began using recording-type measuring instruments, and studying test curves assisted me in solving many, many technical problems. In the multiple hydraulic component system production plants that the author visited in Europe, since the 1990s, factory testing and after-sales service have all begun using recording-type testing instruments, not to mention research and development.

Now, due to advances in electronic technology, even recording-type testing instruments (hydraulic multimeters) produced in Germany that can be used to test common hydraulic systems, with simple configurations, sell for less than 20,000 yuan in China. Therefore, the instrument procurement cost is no longer an obstacle for the vast majority of domestic hydraulic enterprises. Buying instruments is easy, however, this is only the first step. Not having recording-type testing instruments is a low level, having testing instruments but not using them is still a low level. The difficulty lies in use! Because this requires combining theory with practice and having considerable practice in hydraulic technology. Being able to analyze test results and make curves speak is more important. Therefore, the author believes that whether recording-type testing instruments are used and whether test curves can be read can serve as a benchmark for measuring the level of technical capability of hydraulic enterprises.

No matter how many expensive processing machine tools have been purchased, if one is still only relying on pressure gauges to work and does not yet have recording-type testing instruments, it is as backward as still using an abacus for accounting. Performance curves in product manuals cannot be tested by oneself, but only copy those of others. As a hydraulic enterprise, from a worldwide perspective, it can only be considered to have a low technical level.

If an enterprise has recording-type testing instruments, and a few people can use them, and some people can roughly read test curves, it can be considered to have a medium technical level.

Only if factory testing and after-sales service personnel generally know how to use recording-type testing instruments, and there is a group of technical “experts” who can analyze test curves and carry out discussions, can such an enterprise be considered truly high-level.

If test results can be reproduced through simulation, that is high-level research.