Menu

Vane pumps don’t usually fail loudly. They wear out quietly.

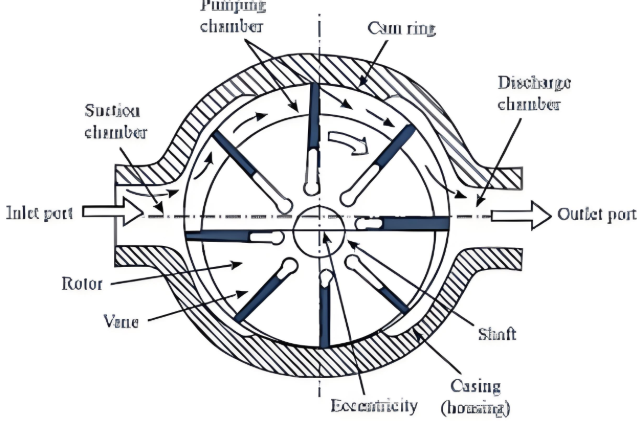

Inside the housing, the rotor doesn’t sit in the center. It’s offset. The rectangular vanes slide in and out of the rotor slots as it spins. Centrifugal force and oil pressure push the vane tips against the cam ring. As the chambers grow and shrink, oil gets pulled in and pushed out.

On paper, it’s simple. In the field, the critical detail is contact pressure at the vane tips. That’s where most failures begin.

Unlike gear pumps, vane pumps don’t tolerate dirt well. You can sometimes get away with dirty oil on a gear pump for months. A vane pump might last weeks.

Most operators don’t even realize they’re running vane pumps. But they’re everywhere:

Pilot systems on Cat 320 excavators

Steering circuits on mid-size John Deere loaders

Older Komatsu equipment running Eaton Vickers VQ pumps

Indoor forklifts from Toyota and Hyster, mainly for noise control

Warehouse forklifts are a good example. Gear pumps whine. Vane pumps hum. That matters when machines run eight hours a day inside buildings.

Back to those Alberta loaders.

Operators had been bypassing the tank breathers during cold starts because they thought frost was restricting airflow. What they didn’t realize was that every time they did that, they were pulling in fine dust and ice crystals directly into the reservoir.

Within three months:

Steering response got slow

Case drain flow doubled

Two pumps seized completely

When we tore them down, the vane tips were razor-thin. The cam rings looked sandblasted.

That was my first real-world lesson in how fast contamination kills vane pumps.

In teardown inspections, the damage follows a predictable pattern:

Vane tip polishing

Cam ring scoring

Internal leakage

Pressure loss

Heat runaway

Once case drain flow hits about 10% of rated output, the pump is already on borrowed time. At that point, you’re just waiting for heat to finish it off.

We logged oil temps on several machines running overheated pilot circuits. Once oil climbs past 82°C (180°F), viscosity drops too far for stable vane sealing. The pumps still turn, but internal slip explodes.

In mining applications, we’ve traced overheating to:

Undersized oil coolers

Plugged heat exchanger fins

Broken fan shrouds

Operators power-washing mud directly into coolers

Most operators never notice heat damage until pressure falls off under load.

Sometimes. Sometimes not.

On Eaton V and VQ series pumps, cartridge kits make rebuilds practical. A good tech with clean tools can swap a cartridge in under two hours. We’ve done it in the field on service trucks more than once.

But here’s the trap:

If the housing is heat-soaked or the shaft bearings are already damaged, the cartridge won’t save the pump. You’ll be back in there in a month.

Cost-wise:

Cartridge kits usually run a few hundred to over a thousand dollars

Full pump replacement is several times that

Labor is often the biggest wildcard

Filtration discipline.

Every long-lasting vane pump I’ve seen had:

Proper tank breathers

10-micron return filtration

Regular oil sampling

No shortcut warm-up procedures in winter

Every early failure I’ve seen came from:

Dirty oil

Bypassed filters

Poor cold-start habits

Vane pumps don’t forgive shortcuts. They work beautifully—until they don’t.

If you’re running vane pumps and don’t know it, that’s already a warning sign. These pumps aren’t fragile, but they are precise. Treat them like gear pumps and they’ll fail like precision equipment always does—quietly, expensively, and right when you need them most.