Menu

Hydraulic cylinders convert pressurized fluid into mechanical force to push, pull, lift, and move heavy loads in machinery. They power equipment across construction, manufacturing, agriculture, and transportation by transforming hydraulic energy into controlled linear motion.

The operating principle comes from Pascal’s Law, discovered in 1653, which states that pressure applied to a confined fluid transmits equally throughout. When hydraulic oil enters the cylinder barrel, it pushes against a piston connected to a rod. Since liquids are incompressible, even small amounts of pressure create substantial force—this is why a 2-inch diameter piston can lift thousands of pounds when proper pressure is applied.

The system consists of a pump that pressurizes hydraulic fluid (typically oil), valves that control flow direction, and the cylinder that executes the work. A single-acting cylinder uses hydraulic pressure for extension and relies on external force or gravity for retraction. Double-acting cylinders apply force in both directions, with fluid entering either side of the piston for precise bidirectional control. This design appears in 70% of industrial hydraulic cylinders because applications like excavator arms and manufacturing presses require controlled movement in multiple directions.

The global hydraulic cylinder market reached $15.7 billion in 2024 and projects to grow at 4.6% annually through 2034, driven largely by construction and agricultural mechanization.

Mobile equipment accounts for 67% of hydraulic cylinder demand. Construction machinery represents the largest single application, followed by agricultural equipment and material handling systems. These cylinders handle environments where mechanical linkages would fail—high force requirements, compact spaces, and harsh operating conditions.

In construction, excavators rely on multiple cylinders to control boom extension, arm articulation, and bucket rotation. A typical 20-ton excavator uses 6-8 hydraulic cylinders, each capable of generating forces exceeding 50,000 pounds. The telescopic cylinders in dump trucks extend up to 20 feet while retracting to a fraction of that length, enabling efficient load dumping in confined job sites.

Manufacturing facilities use hydraulic cylinders in presses that shape metal, injection molding machines that form plastics, and assembly line equipment that positions components. Industrial presses can generate forces reaching several thousand tons through hydraulic multiplication—a small input force on a 2-inch cylinder translates to massive output force on a 12-inch cylinder.

Excavators depend on cylinders for every major movement. The boom cylinder extends and retracts the primary arm, the stick cylinder controls the secondary arm angle, and the bucket cylinder opens and closes the digging implement. Double-acting cylinders enable operators to dig with force while pulling back, then push forward to position loads. Welded body cylinders dominate construction equipment because their one-piece design withstands the impact loads and vibration common in digging and demolition.

Bulldozers use cylinders to angle and tilt blades for grading and earth moving. The blade lift cylinders must support the entire blade weight plus the resistance of material being pushed. Caterpillar’s D11 bulldozer, one of the largest production models, employs cylinders operating at pressures up to 5,000 PSI to move its 24-foot blade through dense soil.

Cranes incorporate cylinders in boom extension, load positioning, and stabilizer deployment. Telescopic cylinders allow boom sections to nest inside each other when retracted, then extend sequentially for maximum reach. A 100-ton mobile crane might extend its boom from 40 feet to over 150 feet using multi-stage telescopic cylinders.

Concrete pumps use cylinders to drive pistons that push concrete through delivery lines at construction sites. These cylinders operate in harsh environments with abrasive materials, requiring chrome-plated rods and reinforced seals to maintain reliability through millions of cycles.

Tractors use hydraulic cylinders to raise and lower implements, control three-point hitch positioning, and operate front loaders. A typical 100-horsepower tractor features 4-6 cylinders working at 2,500-3,000 PSI to lift loads exceeding 5,000 pounds. The agricultural sector in Asia Pacific is driving 25.9% of global hydraulic cylinder demand, with India’s market alone growing at 5.8% annually as farm mechanization expands.

Harvesting equipment employs cylinders to adjust header height, control grain flow, and position cutting mechanisms. Combine harvesters use up to 12 hydraulic cylinders to coordinate the complex movements required for efficient crop processing. These systems must operate reliably in dusty, high-vibration environments while maintaining precise control.

Manufacturing applications span multiple processes. Hydraulic presses in automotive plants form body panels by applying forces up to 2,000 tons. Injection molding machines use hydraulic cylinders to clamp molds, inject material, and eject finished parts. A single automotive plant might contain hundreds of hydraulic cylinders across stamping presses, assembly fixtures, and material handling equipment.

The metal fabrication industry uses hydraulic cylinders in shearing machines, bending presses, and punch presses. These cylinders must deliver consistent force across the full stroke length—a metal brake bending 12-foot sheets requires even pressure distribution to prevent warping.

Welded body cylinders feature barrels welded directly to end caps, creating a strong single-piece construction. They’re the standard in mobile equipment because the design eliminates potential leak points from threaded connections. The welded segment held 53.4% market share in 2024, with demand concentrated in construction and agricultural machinery.

Tie-rod cylinders use external threaded rods to hold end caps to the barrel. This design simplifies disassembly for maintenance, making them common in industrial factories where regular seal replacement is part of preventive maintenance programs. The National Fluid Power Association standardizes tie-rod dimensions, allowing cylinders from different manufacturers to interchange.

Telescopic cylinders nest multiple stages to achieve long stroke lengths from compact retracted sizes. Dump trucks use 3-5 stage telescopic cylinders that extend 15-20 feet while collapsing to under 6 feet. Each stage extends sequentially, with hydraulic fluid flowing through passages that activate progressively larger pistons. This design sacrifices some force capacity—the extended stages can’t support as much load as a single-stage cylinder—but the space savings are essential in mobile applications.

Ram cylinders have thick piston rods with no separate piston, used primarily for pushing operations. Hydraulic jacks in service stations are ram cylinders that lift vehicles by extending the rod against the frame. These cylinders excel in vertical lifting because the large rod diameter resists side loads that would damage conventional cylinder designs.

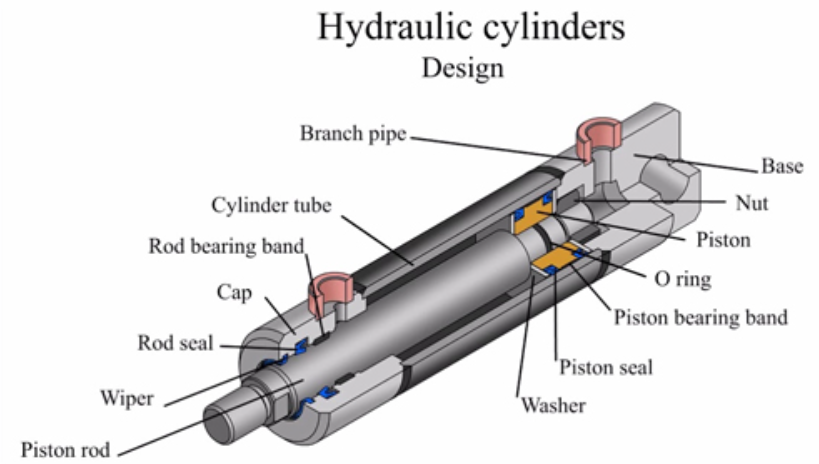

The cylinder barrel contains hydraulic pressure and guides the piston. Barrels are typically made from seamless steel tubing with internal surfaces honed to 4-16 microinch finish. This smooth surface finish is critical—roughness accelerates seal wear and allows fluid leakage past the piston. Most barrels are manufactured from DOM (drawn over mandrel) steel tubes that provide consistent wall thickness and material properties.

Piston rods transfer force from the piston to the external load. They’re usually chrome-plated cold-rolled steel with hardness values of 55-60 HRC to resist wear from seal friction and environmental contamination. The chrome plating thickness ranges from 0.001 to 0.003 inches, providing a hard surface that maintains seal contact even after millions of cycles.

Seals prevent fluid leakage and contamination entry. Piston seals separate the two pressure chambers inside the barrel, while rod seals keep fluid inside the cylinder head. Modern seals use polyurethane, nitrile rubber, or fluorocarbon compounds selected based on operating temperature and fluid compatibility. High-temperature applications (above 200°F) require Viton seals, while standard industrial applications use more economical polyurethane seals.

Mounting configurations vary by application. Clevis mounts allow angular movement between the cylinder and load, preventing side loads that cause premature failure. Flange mounts bolt directly to equipment frames for rigid installations. Trunnion mounts permit cylinder rotation, used in applications like excavator arms where the cylinder must swing through a wide arc.

Double-acting cylinders represent 71% of market revenue because most applications require controlled force in both directions. Industrial automation is driving demand for cylinders with integrated sensors that monitor position, pressure, and load. These smart cylinders enable predictive maintenance—analyzing seal wear patterns and fluid conditions to schedule replacements before failures cause downtime.

The construction equipment sector, experiencing steady growth in Asia Pacific and North America, consumes hydraulic cylinders at accelerating rates. Infrastructure investment in India and Southeast Asia is pushing regional demand up 5.5-6% annually. North American construction activity, rebounding from pandemic disruptions, is driving renewed capital equipment purchases and replacement cylinder demand.

Material handling equipment in warehouses and distribution centers increasingly uses hydraulic cylinders for lift and tilt functions. The growth of e-commerce and same-day delivery requirements has multiplied forklift and pallet jack deployments, each containing 2-4 hydraulic cylinders for load handling.

Environmental regulations are pushing development of bio-based hydraulic fluids and more efficient cylinder designs. Reducing fluid volumes through optimized bore and rod sizing cuts both initial fill costs and potential environmental impact from leaks. Some manufacturers are developing cylinders with embedded flow restrictions that reduce energy consumption by 15-20% compared to conventional designs.

Hydraulic fluid is incompressible while air compresses under pressure, allowing hydraulic cylinders to generate forces 10-20 times greater than comparable pneumatic cylinders. A 2-inch bore hydraulic cylinder at 3,000 PSI produces over 9,000 pounds of force, whereas a pneumatic cylinder at typical 100 PSI delivers only 300 pounds from the same bore size.

Industrial cylinders in controlled environments routinely achieve 5-10 million cycles before requiring seal replacement. Mobile equipment cylinders in construction face harsher conditions—contamination, impact loads, temperature extremes—and typically need rebuilding after 2,000-5,000 operating hours. Proper maintenance, including keeping hydraulic fluid clean and inspecting seals regularly, extends cylinder life significantly.

Standard seals function between -20°F and 200°F. Applications outside this range require specialized seal materials and fluid formulations. Arctic equipment uses special cold-weather hydraulic oils and fluorosilicone seals that remain flexible below -40°F. High-temperature applications like steel mill equipment use Viton seals and synthetic fluids rated to 300°F.

Contaminated fluid accounts for 75% of hydraulic system failures. Dirt particles act as abrasives, cutting seals and scoring cylinder bores. Insufficient fluid levels cause cavitation that erodes internal surfaces. Side loading from misalignment bends piston rods and tears rod seals. Regular fluid filtration, proper cylinder mounting, and scheduled seal inspection prevent most failures.

The versatility of hydraulic cylinders—operating reliably across temperature extremes, generating massive forces from compact packages, and adapting to countless mounting configurations—explains their dominance in heavy equipment. As industries push toward electrification and automation, hydraulic cylinders are incorporating sensors and electronic controls while maintaining the fundamental force multiplication that made them essential. The technology that Pascal discovered nearly 400 years ago continues powering modern machinery through continuous refinement of materials, seals, and system integration.