Menu

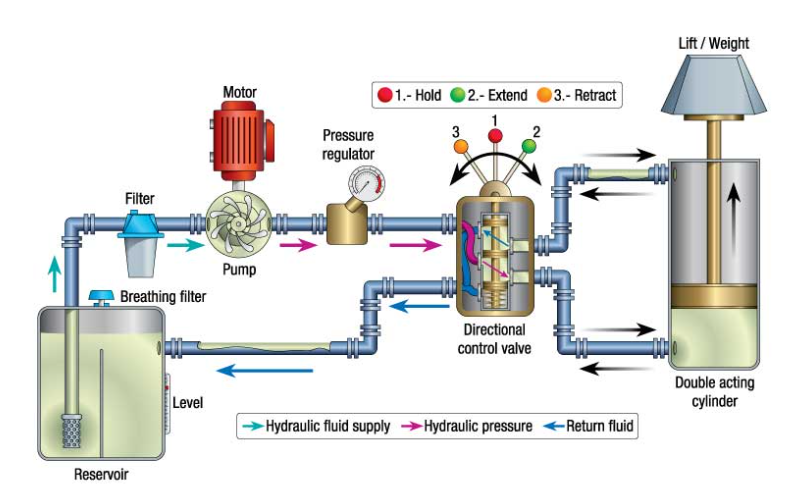

A hydraulic pump converts mechanical power into hydraulic energy by creating fluid flow under pressure. It generates a vacuum at its inlet that draws fluid from a reservoir, then delivers this pressurized fluid to drive hydraulic systems in machinery ranging from excavators to automotive braking systems.

The operation of a hydraulic pump centers on positive displacement mechanics. When the pump’s drive mechanism—powered by an electric motor, internal combustion engine, or other prime mover—activates, it creates a partial vacuum at the inlet port. Atmospheric pressure then forces hydraulic fluid from the reservoir into the pump chamber. The pump’s internal elements (gears, vanes, or pistons) mechanically compress and move this fluid toward the outlet, creating the pressure needed to perform work.

This differs fundamentally from how these pumps are sometimes misunderstood: the pump doesn’t generate pressure directly. Rather, it produces flow. Pressure develops only when this flow encounters resistance from the system’s load. Without a load, outlet pressure remains at zero. This principle explains why hydraulic pumps require careful system design—the pressure level depends entirely on what the pump needs to move or lift.

The mechanical action follows a continuous cycle: intake, compression, and discharge. During intake, expanding chambers draw fluid in. During compression, these chambers decrease in volume, raising fluid pressure. During discharge, the high-pressure fluid exits toward the hydraulic actuators or cylinders that perform the actual work. This cycle repeats hundreds or thousands of times per minute, depending on pump speed.

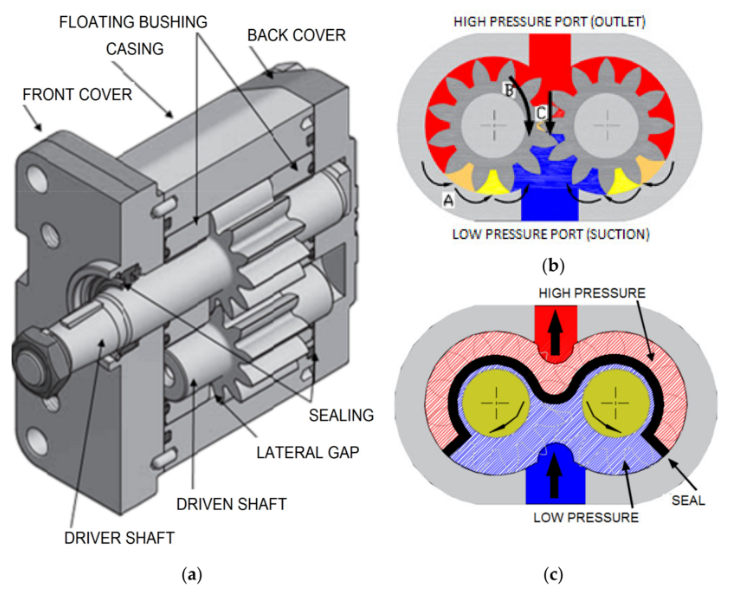

Gear pumps represent the most widely adopted hydraulic pump design, accounting for 39.6% of the market in 2024. Two meshing gears rotate within a tight-tolerance housing. As the gears turn, they create expanding chambers on the inlet side that fill with fluid, then shrinking chambers on the outlet side that pressurize and expel it.

External gear pumps feature two identical gears on separate shafts. Internal gear pumps use a larger outer gear with an inner gear rotating inside it. The trapped fluid between gear teeth moves around the pump’s perimeter from inlet to outlet. Modern designs incorporate helical gear teeth and precision-machined profiles that reduce pressure ripple and noise—a significant improvement over older models.

Gear pumps excel in applications requiring moderate pressure (up to 3,000 PSI), simple maintenance, and cost efficiency. Their fixed displacement design delivers consistent flow proportional to shaft speed. With volumetric efficiency around 90%, they handle contamination better than more precise pump types due to looser internal tolerances.

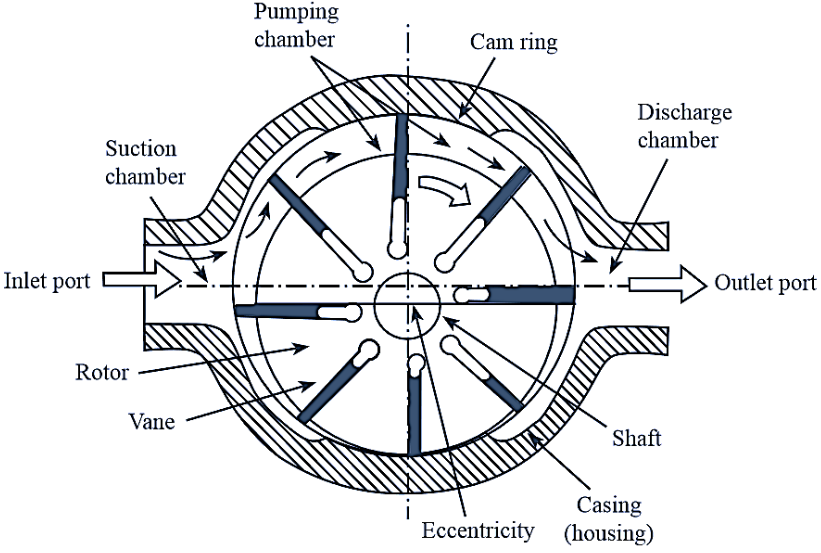

A vane pump contains a slotted rotor mounted off-center within a circular chamber. Spring-loaded or hydraulically-loaded vanes extend from the rotor slots. As the rotor turns, vanes maintain contact with the chamber wall through centrifugal force and hydraulic pressure.

The off-center mounting creates variable chamber volumes. Chambers expand at the inlet, drawing in fluid. They contract at the outlet, pressurizing and expelling it. This design produces smoother flow with less pulsation than gear pumps. Vane pumps operate efficiently up to 200 BAR (2,900 PSI) and generate minimal noise during operation.

Variable displacement vane pumps adjust flow by altering the eccentricity between rotor and housing. This allows flow modulation without changing shaft speed—useful for applications with varying hydraulic demands. Vane pumps work best with lower viscosity fluids and self-compensate for wear through the self-adjusting vane mechanism.

Piston pumps deliver the highest pressure capability and efficiency among hydraulic pump types. Multiple pistons reciprocate within cylinder bores, driven by a rotating mechanism that converts rotary motion to linear piston movement. This design handles pressures exceeding 350 BAR (5,000 PSI) with volumetric efficiencies up to 95%.

Axial piston pumps arrange cylinders parallel to the drive shaft axis. Pistons connect to a swashplate or wobble plate angled to the drive shaft. As the shaft rotates, pistons move in and out of their bores—drawing fluid during extension, expelling it during retraction. Variable displacement models adjust the swashplate angle to change piston stroke length, modifying flow output without altering shaft speed.

Radial piston pumps position cylinders perpendicular to the drive shaft in a circular array. An eccentric cam drives the pistons outward and inward as it rotates. These pumps excel at very high pressures and work effectively with viscous fluids. Their robust construction suits heavy-duty industrial applications.

The tight tolerances required for piston pump efficiency make them sensitive to fluid contamination. Proper filtration becomes critical—particles that gear pumps tolerate can cause rapid wear or failure in piston designs. This explains their higher maintenance requirements and initial cost compared to gear or vane pumps.

Most hydraulic systems use positive displacement pumps, which move a fixed fluid volume per shaft rotation. Internal seals prevent fluid from slipping backward, ensuring nearly all pumped volume reaches the outlet. If you blocked a positive displacement pump’s outlet while it ran, pressure would rise until something failed—the pump case, drive shaft, or prime mover would break before flow stopped.

Non-positive displacement pumps (like centrifugal pumps) generate continuous flow through impeller action but lack internal sealing against backflow. Their output drops significantly as pressure increases. Blocking their outlet simply stops flow while the impeller continues spinning. These suit applications requiring high flow at low pressure but perform poorly in hydraulic systems needing consistent pressure regardless of load.

The distinction matters for system design. Positive displacement pumps maintain nearly constant flow across varying pressure conditions, making them reliable for applications requiring precise force control. Non-positive displacement pumps work well for fluid transfer but can’t reliably power hydraulic actuators.

Fixed displacement pumps deliver the same volume per revolution continuously. Flow varies only with shaft speed. These simpler designs cost less and require minimal maintenance. Open-center hydraulic systems—where excess flow returns to the reservoir when not needed—commonly use fixed displacement pumps.

Variable displacement pumps adjust their output volume per revolution through internal controls. Mechanisms like adjustable swashplates or variable eccentricity modify the displacement chamber volumes during operation. This capability offers several advantages: matching pump output to instantaneous system demand, reducing energy waste, and enabling closed-center systems where the pump only supplies needed flow.

Pressure-compensated variable pumps automatically reduce flow as system pressure approaches a set maximum. Load-sensing controls adjust displacement based on signals from downstream valves, optimizing efficiency. These sophisticated controls increase pump complexity and cost but significantly reduce energy consumption—critical for mobile equipment where fuel efficiency matters or industrial systems targeting sustainability goals.

The 2024 market shows growing adoption of variable displacement designs as industries pursue energy efficiency. Variable displacement piston pumps, while representing a smaller market share than gear pumps, demonstrate the fastest growth rate due to their superior power density and controllability.

Construction represents the largest end-use segment at 29.2% of the hydraulic pump market in 2024. Excavators, loaders, cranes, and concrete pumps depend on hydraulic power for all major functions. A typical excavator uses multiple hydraulic pumps: a main pump driving swing motors and boom cylinders, plus auxiliary pumps for attachments.

These applications demand high reliability under harsh conditions—dirt, temperature extremes, shock loads. Piston pumps predominate in large equipment due to their power density and pressure capability. A single variable displacement piston pump can deliver over 400 liters per minute at 350 BAR, sufficient to power a 50-ton excavator’s multiple functions.

Hydraulic pumps operate critical safety and comfort systems in vehicles. Power steering systems use vane or gear pumps to reduce steering effort. Anti-lock braking systems (ABS) rely on precision hydraulic pumps to modulate brake pressure during emergency stops. Active suspension systems employ hydraulic actuators powered by electric pumps.

The automotive sector shows interesting trends toward electrification. Traditional engine-driven hydraulic pumps face replacement by electric motor-driven pumps in hybrid and electric vehicles. This shift enables on-demand operation rather than continuous running, improving energy efficiency. The global hydraulic pump market for automotive applications continues expanding as advanced driver assistance systems (ADAS) and active safety features proliferate.

Manufacturing facilities use hydraulic pumps across diverse processes: metal forming presses, injection molding machines, material handling systems, and automated assembly equipment. These applications value the precise force control and power density hydraulic systems provide.

Hydraulic presses exemplify this sector’s requirements. A 1,000-ton press might use a 100-liter variable displacement piston pump operating at 300 BAR. The pump runs continuously but adjusts output to match pressing cycle demands—full flow during the forming stroke, minimal flow while holding pressure, nearly zero during part removal. This load-sensing operation reduces energy consumption by 30-40% compared to fixed displacement designs.

Farm equipment relies heavily on hydraulic power for implements and steering. Tractors use multiple hydraulic circuits: one for steering, another for hitched implements (plows, cultivators), and often a third for front-end loaders. Modern precision agriculture equipment adds hydraulic drives for variable-rate fertilizer spreaders and seed planters.

The agricultural market favors gear pumps for their simplicity, contamination tolerance, and cost-effectiveness. Farm environments expose equipment to dust, mud, and irregular maintenance—conditions where gear pumps’ robust design proves advantageous despite lower efficiency than piston alternatives.

Aircraft hydraulic systems operate at higher pressures (3,000-5,000 PSI becoming standard) than most industrial applications. Variable displacement piston pumps with pressure compensation dominate due to their power density and precise control. A commercial jetliner typically has three or four independent hydraulic systems, each with multiple pumps, powering flight controls, landing gear, brakes, and cargo doors.

Aerospace applications demand the highest reliability and often specify redundant pump systems. The pumps must function across extreme temperature ranges and altitudes while maintaining precise pressure control. This sector drives innovations in pump materials, sealing technologies, and contamination resistance that later diffuse to industrial applications.

Choosing an appropriate pump type requires analyzing several interdependent factors. The selection process typically starts with defining the application’s pressure and flow requirements, then considers operational environment, energy efficiency goals, and maintenance capabilities.

Operating Pressure Requirements: Applications under 3,000 PSI generally suit gear pumps or vane pumps. The 3,000-5,000 PSI range typically requires piston pumps, particularly for continuous operation. Above 5,000 PSI, axial or radial piston pumps become necessary. The hydraulic pump market shows 51% of pumps sold operate at up to 3,000 PSI, reflecting the prevalence of moderate-pressure applications.

Flow Characteristics: Fixed displacement pumps work well when the application requires consistent flow at varying pressures. Variable displacement pumps excel when flow requirements fluctuate or when energy efficiency matters. Load-sensing variable pumps offer optimal efficiency for mobile equipment and industrial machines with varying duty cycles.

Fluid Compatibility: Piston pumps demand clean, low-viscosity fluids and sophisticated filtration. Gear pumps tolerate higher viscosity and moderate contamination. Vane pumps sit between these extremes, offering good efficiency with medium-viscosity fluids. The fluid type also influences sealing materials and housing coatings—biodegradable hydraulic fluids, gaining adoption for environmental reasons, may require different seal compounds than traditional petroleum oils.

Power Source: Electric motor drive suits stationary industrial equipment, offering precise speed control and clean operation. Internal combustion engines power mobile equipment, directly coupling to pumps via power take-off shafts or hydraulic couplings. Pneumatic drive using compressed air works for portable tools in hazardous environments where electric sparks or combustion present risks. Manual hydraulic pumps serve applications requiring portability without power sources—rescue equipment, portable jacks, maintenance tools.

Maintenance Capabilities: Gear pumps need minimal maintenance beyond periodic seal replacement and fluid changes. Piston pumps require skilled technicians for repair and have shorter service intervals due to tight tolerances. Organizations with limited maintenance capabilities often choose gear pumps even when piston pumps would offer better performance, accepting lower efficiency as a trade-off for reduced maintenance complexity.

The global hydraulic pump market reached $10.64 billion in 2023 and projects growth to $14.36 billion by 2031, representing a 3.82% compound annual growth rate. This expansion reflects increasing automation across industries, infrastructure development in emerging economies, and the ongoing replacement of aging hydraulic systems with more efficient designs.

Asia-Pacific dominates market share, driven by manufacturing growth in China and India plus massive infrastructure projects. Industrial production in the euro area grew 1.8% in August 2024, indicating sustained European demand. North America shows steady growth concentrated in construction, agriculture, and energy sectors.

Recent technological developments focus on three areas: electrification, digitalization, and sustainability. Electro-hydraulic pumps integrate electric motors with variable-speed drives, enabling precise flow control and significant energy savings. Sensors and IoT connectivity allow real-time pump monitoring, predictive maintenance, and performance optimization. Manufacturers increasingly develop pumps using biodegradable fluids, reducing environmental impact from leaks.

In November 2024, Fortress Investment Group acquired TH Holdings (including Texas Hydraulics and Oilgear), signaling industry consolidation around companies with custom engineering capabilities. In January 2024, Grundfos launched a next-generation SP 6-inch pump with enhanced energy efficiency for groundwater applications. These developments reflect market movement toward specialized, high-efficiency solutions rather than commodity products.

The construction sector’s demand particularly shapes market evolution. Excavator manufacturers increasingly specify load-sensing variable displacement pumps to meet emissions regulations by reducing engine load. The shift toward electric construction equipment accelerates innovation in compact, high-efficiency pumps suitable for battery-powered systems.

Hydraulic pump reliability depends heavily on proper maintenance, with 95% of failures traceable to contamination, aeration, cavitation, overheating, or improper fluid selection.

Contamination remains the leading cause of premature pump failure. Particles as small as 10 microns can damage piston pump components with clearances of 5-15 microns. Implementing filtration meeting ISO 4406 cleanliness standards (typically 18/16/13 or better for piston pumps) prevents most contamination-related failures. Gear pumps tolerate coarser filtration (20/18/15) due to larger clearances.

Cavitation occurs when pump inlet conditions create vapor bubbles in the fluid. These bubbles collapse on the pressure side, generating shock waves that erode metal surfaces. Proper inlet line sizing, adequate fluid level, and appropriate fluid viscosity prevent cavitation. Symptoms include noise, vibration, and rapid seal wear.

Aeration differs from cavitation—it involves air entrained in the fluid rather than vapor formation. Aeration causes erratic operation, reduced performance, accelerated oxidation of hydraulic fluid, and potential pump damage. Proper reservoir design with adequate deaeration time, tight inlet connections, and shaft seals prevent air ingestion.

Overheating accelerates fluid degradation, reduces viscosity (increasing internal leakage), and damages seals. Heat generation comes from inefficiency—essentially friction within the pump and fluid throttling losses in the system. Variable displacement pumps reduce heat by matching output to demand. Heat exchangers become necessary when ambient conditions or duty cycles generate excessive heat.

Regular maintenance includes fluid analysis (checking for contamination, water content, and degradation), filter replacement per manufacturer schedules, seal inspection and replacement, and verification of proper operating parameters (pressure, temperature, flow). Predictive maintenance using vibration analysis, thermal imaging, and flow monitoring can identify developing problems before catastrophic failure.

A hydraulic pump converts mechanical energy to pressurized fluid flow for powering machinery, operating at high pressures (often 1,000-5,000 PSI). A water pump moves water from one location to another, typically at lower pressures focused on flow volume rather than pressure generation. While both move fluids, hydraulic pumps are specifically designed for the tight tolerances and high pressures needed in power transmission systems.

No. Hydraulic pumps create flow, not pressure directly. Pressure develops only when that flow encounters resistance from the system’s load or a restriction. An unloaded pump with its outlet open to atmosphere shows near-zero pressure despite generating full flow. This fundamental principle explains why hydraulic systems require proper sizing—the load determines pressure while the pump provides flow.

Piston pumps require more complex manufacturing with tighter tolerances, use more components (multiple pistons, swashplates, valve plates), and often include sophisticated displacement control mechanisms. These factors increase production costs. They also demand cleaner fluid and more frequent maintenance. However, their higher efficiency (often 95% vs. 90% for gear pumps) and pressure capability can justify the extra expense in demanding applications.

Service life varies dramatically based on pump type, application, and maintenance. Well-maintained gear pumps in moderate-duty applications can run 10,000-15,000 hours. Piston pumps in clean systems with proper maintenance may reach 15,000-25,000 hours. Mobile equipment operating in harsh environments might see 5,000-8,000 hours. Regular fluid analysis, appropriate filtration, and prompt attention to abnormal symptoms maximize service life.

A hydraulic pump represents a critical energy conversion component, translating rotary mechanical power into the pressurized fluid flow that drives countless industrial and mobile systems. The technology continues evolving toward greater efficiency, better control, and reduced environmental impact—trends that will define the next generation of hydraulic power systems. Whether powering a 200-ton excavator or a precision manufacturing press, the pump remains the heart of the hydraulic system, and understanding its operation enables better system design, more informed purchasing decisions, and more effective maintenance strategies.

The diversity of pump types—gear, vane, and piston, each with multiple variations—reflects the wide range of applications hydraulic power serves. Matching pump characteristics to application requirements determines system performance, efficiency, and reliability. As industries push toward automation, electrification, and sustainability, hydraulic pump technology adapts, integrating digital controls, energy recovery systems, and eco-friendly fluids while maintaining the fundamental principles of positive displacement mechanics that have powered machinery for over a century.