Menu

The Chinese machinery industry standard JB/T7033-2007 “General Rules for Hydraulic Transmission Measurement Technology” (modified adoption of ISO 9110-1:1990) defines: static condition – “a condition in which parameters do not change with time.”

However, in actual hydraulic systems, because the flow discharged by all hydraulic pumps has more or less pulsation, when encountering hydraulic resistance, this leads to pressure pulsation as well. Therefore, as long as the system is working, the pressure and flow in pump outlets, pipelines, hydraulic valves, and hydraulic cylinders are variable, and basically there will not be a state where parameters do not change with time. Therefore, this type of condition is not particularly worthy of investigation.

Steady state, as the name implies, means stability.

Because in actual systems during operation, parameters such as pressure and flow are all changing, the above-mentioned standard settles for the next best thing and also defines steady-state condition – “a condition in which the mean value of a variable does not change with time, or the variation of the instantaneous value of the variable is periodic and can be described by a simple mathematical formula.” That is, as long as the average value basically does not change, it can be considered steady state.

Note: The variable here should not be understood as all variables in the system. Because, for an object, as long as its velocity is not zero, its displacement (average value) will definitely change with time. According to the original text in ISO 9110-1:1990: “Conditions under which the mean of a variable does not change with time and the variation of an instantaneous value of that variable is cyclic and can be described by a simple mathematical expression,” it should be understood as “a certain variable.”

GB/T 17446-2012 “Fluid Power Systems and Components – Vocabulary” (identical to ISO 5598:2008) translates it as “relevant parameters,” which can also avoid misunderstanding.

In actual hydraulic technology, what is commonly said, such as the pressure at a certain point in the system being 15MPa, the flow in a certain flow path being 40L/min, etc., all refer to steady state, that is, average values.

Static state can be considered a special case of steady state: when the flow entering the hydraulic cylinder is zero, at this time, the hydraulic cylinder’s velocity is zero, therefore, the load’s position does not change.

It is generally believed that steady-state performance is the performance of hydraulic components or systems under steady-state conditions. The following characteristics of hydraulic valves all belong to steady-state performance:

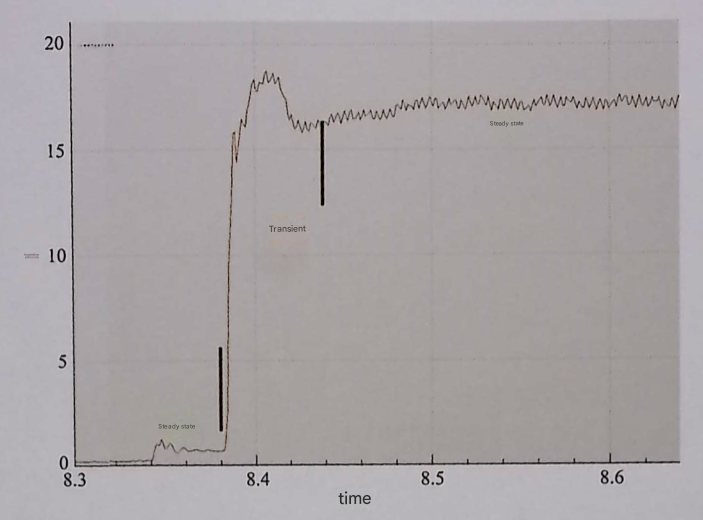

The state after a system leaves one steady state and before entering another steady state is called transient state, also called dynamic state. The measured pressure changing from steady state to transient state and then recovering to steady state is an example of this process.

Generally understood, transient state is the process of finding a new equilibrium point, during which not only pressure but also many other parameters (spool moving velocity, opening, flow, etc.) will change.

The instantaneous response performance of components and systems to changes in load, disturbance, and commands is called transient response performance, or transient performance for short, also called dynamic performance.

Components and systems with good transient performance can quickly adapt to changes and enter a new steady state.

If a component or system requires a long adaptation time, or has large overshoot, or even oscillates continuously and cannot enter steady state at all, the transient performance is generally considered poor.

The transient performance of a hydraulic system depends not only on the components used but also is closely related to the system’s configuration.

Hydraulic systems will not always remain in a certain steady state. Because the task of hydraulic transmission is to make the load change from stationary to moving, from moving to stationary, from slow motion to fast motion, from fast motion to slow motion. In a word, it is to change the state. The most important way to accomplish these tasks at present is to control the movement of the spool, changing its position relative to the valve body, thereby changing the opening.

In theory, closed-loop control that can perfectly achieve the desired target is actually continuously adjusting the opening.

When the opening changes, the flow passing through it will also change. When the flow changes, the pressure will also change accordingly, but both have lag. These all depend on the transient response performance of the valve and system.

The various control forces and resistances acting on the spool have been analyzed before, and these forces and influencing factors have been roughly and briefly summarized.

The resistances encountered by spool movement include hydraulic pressure, spring force, friction force, and gravity.

Hydraulic pressure is mainly determined by the valve’s structure and the position of the spool, and can be estimated, but is also affected by flow forces and is difficult to estimate accurately.

Flow forces are determined by the pressure differential across the opening and the flow passing through the opening.

Spring force is mainly determined by the amount of spring compression (including spool displacement) and can be estimated.

Friction force mainly varies with the moving velocity of the spool relative to the valve body, but is affected by many factors such as positional deviation of machined shapes, gap conditions after assembly, roughness of contact surfaces, lubrication conditions, and oil contamination conditions. Therefore, it is basically impossible to calculate theoretically.

Although gravity may also affect spool movement, relative to other forces in modern hydraulics, it is often small enough to be neglected.

All objects have mass, and spools are no exception. Although the weight of a spool can often be neglected, its mass cannot be ignored when examining the valve’s transient performance. Because, for a solid in translation, its inertia is its mass (rotating spools are currently rarely used, and generally the rotation speed is also very low, so the effect of inertia is not large; the following is only for spools in translation), and inertia hinders changes in motion state, somewhat like a resistance, which is why it is often called inertial force. In fact, the hindrance of inertia to object movement is fundamentally different from friction force, spring force, etc.: inertia does not affect the net force.

Control forces are roughly mechanical, manual, and electrical. When these forces are not large enough or when the control force is insufficient for other reasons, flow force and pneumatic force are also used.

Control force reflects the operator’s expectation, and the actual opening of the spool is reality; there is always lag between expectation and reality. Because the difference between control force and resistance, divided by inertia, is only the acceleration of spool movement. The accumulation of acceleration is velocity, and the accumulation of velocity is the spool’s displacement. Only when the spool’s position changes can the opening possibly change.

The pressure differential across the opening and the opening determine the flow, sometimes also affected by oil viscosity. The flow and the size of the opening determine the flow velocity at the opening, and flow reduces hydraulic pressure, which is the so-called flow force.

The process of the spool moving under the action of these control forces and resistances determines the valve’s transient performance and will affect the system’s transient condition.

For a spool to move from one position to another, from rest to motion, the velocity must increase from zero, which requires acceleration.

Spool acceleration = (control force acting on spool – resistance) / spool inertia.

Therefore, as long as there is inertia, acceleration cannot be infinite, and velocity cannot be infinite either.

Therefore, no matter how light the spool is, movement takes time. Even for on-off valves, although the spool moves relatively fast and the movement time is generally not of concern under normal circumstances, there is still a process. And this process is definitely not uniform velocity.

Its velocity variation with time can be simplified, and the area under the velocity-time curve is the spool’s displacement.

It can be derived that: if it is desired to complete displacement S in time t₁, the maximum velocity needed is

Vₘₐₓ = 2S/t₁

The acceleration needed during the acceleration phase is

a = 2Vₘₐₓ / t₁ = 4S / t₁²

The net force acting on the spool needed during the acceleration phase (i.e., control force – resistance) is

F = ma = 4mS / t₁²

Where m is the spool inertia.

From the formula, it can be seen that the control force needed to overcome inertia (after deducting resistance) is inversely proportional to the square of the time needed to complete, so it should not be underestimated sometimes.

For a greatly simplified spool model, assuming that the thrust F moving the spool comes only from the pressure differential of the oil at both ends of the spool, and all resistances are neglected, then the pressure differential needed is

Δp = p₁ – p₂ = F/A = 4F/πd²

If this spool has a diameter of 12mm and length of 50mm (steel, density = 7.9g/cm³), the mass is approximately 45g. If it is desired to complete a displacement of 5mm in 20ms, it can be estimated that: the acceleration needed is approximately 50m/s² (gravitational acceleration is 9.8m/s²), the thrust F needed is approximately 2.2N, and the pressure differential is approximately 0.02MPa.

If the spool has a diameter of 18mm and length of 100mm (mass approximately 201g), and it is desired to complete a stroke of 8mm in 10ms, then the acceleration needed is approximately 320m/s² (32 times gravitational acceleration), the thrust needed is approximately 64N, and the pressure differential is approximately 0.25MPa.

If the spool movement approximates “uniform acceleration start, rapid braking” (such as moving to a limit position and being stopped by the valve body), then the acceleration needed during start-up can be lower.

But if the movement process approximates “long stroke, with a section of uniform motion,” then higher acceleration is needed, that is, higher thrust.

Actual conditions are generally more complex: overshooting, rebounding, etc.

As mentioned before, after the electromagnet is energized, the increase in current and electromagnetic force is also gradual, with a non-uniform process.

In short, for a spool to move from one position to another always requires some time (although it may be very short). During this time, some other factors are also changing, which determine the valve’s transient performance (such as overshoot in relief valves, starting jump in flow valves, etc.). The valve’s transient performance in turn affects the entire hydraulic system and even the main machine’s transient performance.

In hydraulic systems, except for the oil tank and the return oil line and suction line connected to it which are generally open, from the pump outlet to the directional control valve, hydraulic cylinder, all the way to before the return oil line, it can always be seen as one or several (separated by valves) closed chambers. Hydraulics works by relying on the pressure formed in closed chambers.

When oil with volume ΔV is forcibly pressed into a chamber already filled with oil, the oil pressure will rise.

If the change in container volume caused by the pressure rise is neglected, the relationship between the pressure rise Δp and the pressed-in volume ΔV is roughly

Δp = EΔV/V

Where E is the bulk modulus of the oil, 1000~3500MPa, varying with the oil’s pressure and temperature, etc.

That is, if E is 1800MPa, when the pressed-in volume ΔV is 1% of the original volume V, the pressure will increase by approximately 18MPa.

If the time taken to press in oil ΔV is Δt, then the pressure rise rate during this time is

Δp/Δt = E(ΔV/Δt)/V

To express it more accurately, differential form can be used: because the differential form of ΔV/Δt is dV/dt (i.e., flow rate q), the pressure rise rate is

dp/dt = qE/V

Assuming V=1L and q=1L/min, the pressure rise rate is 1800MPa/min = 30MPa/s, and ordinary containers would probably burst in a few seconds.

The process of hydraulic pressure pushing the spool and opening the flow path (such as the opening of a relief valve) can be simplified, assuming: the effective acting area A of the oil on the spool remains approximately constant; the flow path opening area is approximately πDxₜ (where D is the diameter at the spool opening); the effect of spool movement on spring force is ignored, considering the spring pressure to be approximately equal to the spring preload pressure.

The chamber in front of the spool is closed and filled with oil, pressure pₜ is zero; the spool is pressed against the valve body by spring pressure, displacement xₜ is zero, and the flow path is closed.

When t < t₁, because the chamber pressure pₜ is lower than the spring pressure p₀, it cannot push open the spool, and the flow path remains closed. The pumped-in flow q₀ is completely compressed, causing the chamber pressure pₜ to rise rapidly, with a rise rate of

dp/dt = q₀E/V

Until time t₁, the chamber pressure pₜ reaches the spring pressure p₀.

Because the spool has just started moving and the opening is not large, only part of the pumped-in flow q₀ flows out through the opening:

qₜ = CπDxₜ√pₜ

Where C is the opening flow coefficient.

The remaining flow q₀-qₜ causes pressure pₜ to continue rising, but the rise rate slows:

dp/dt = (q₀ – qₜ)E/V

Until time t₂, the flow qₜ flowing out through the opening equals the pumped-in flow q₀, and pressure pₜ stops rising.

But because chamber pressure pₜ still exceeds spring pressure p₀, the spool displacement continues to increase, only the speed begins to slow.

Until time t₃, chamber pressure pₜ equals spring pressure p₀, and spool displacement stops increasing (ignoring small amplitude movement of the spool due to inertia).

Because chamber pressure pₜ is lower than spring pressure p₀, spool displacement begins to decrease.

Until time t₄, outflow qₜ equals pumped-in flow q₀, and pressure pₜ stops falling.

But at this time pressure pₜ is still lower than spring pressure p₀, and spool displacement continues to decrease.

Until time t₅, chamber pressure pₜ equals spring pressure p₀, spool displacement stops decreasing, but pressure pₜ continues to rise.

The subsequent condition will repeat (similar to t₁ to t₅). If there is completely no friction force or other damping factors, pressure pₜ and spool displacement will oscillate continuously.

In actual systems, there will be some friction force; and the spring chamber is filled with oil, and the oil passing through pipelines to the oil tank will produce hydraulic resistance. The larger the valve opening, the more flow passes through, and the greater the back pressure caused by pipeline hydraulic resistance. These will gradually reduce the oscillation amplitude, and after a period of time, the motion enters steady state.

The above analysis is greatly simplified. Under different friction forces and circuit hydraulic resistances, the pressure variation curve will have different forms.

When directional control valves switch and hydraulic cylinders start, due to the inertia of the piston and load and other resistances, a similar pressure overshoot oscillation process will also occur.

Pressure changes cause flow changes through the opening, which in turn may cause pressure changes – pressure in hydraulic systems is variable!

To describe these variable pressures, GB/T 17446-2012 “Fluid Power Systems and Components – Vocabulary” (identical to ISO 5598:2008) suggests multiple terms.

Using a spring (rubber band) to tie a small ball constitutes a vibration system. Pull the ball downward and release it, and the ball will vibrate up and down for a long time without settling. During this time, the ball’s displacement, velocity, acceleration, spring force received, etc., are constantly changing.

If air friction and other hindering factors are ignored, the force balance equation of the ball is

mg – T = ma = md²x/dt²

Because the spring force T = Gx (where G is spring stiffness), the equation can be written as

d²x/dt² + (G/m)x = g

From this second-order differential equation, the displacement of the ball’s up and down vibration can be derived:

x(t) = C₁sin(ωt) + C₂

Coefficient C₁ reflects the amplitude (depending on initial force); coefficient C₂ reflects the offset of the vibration center (depending on ball gravity mg and spring stiffness).

The angular frequency of vibration is

ω = √(G/m)

From this, the vibration frequency of the ball-spring system can be obtained:

fz = √(G/m) / 2π

From the formula, it can be seen that: the higher the spring stiffness G and the smaller the ball inertia m, the higher the vibration frequency fz.

This frequency is determined jointly by the spring force and ball inertia, and is unrelated to factors such as ball gravity and initial pulling force; even if the amplitude decreases due to resistance, the frequency will not change, so it is called the system’s natural frequency (or self-vibration frequency).

If the unit of spring stiffness G is taken as N/mm and the unit of inertia m is taken as g, the estimation formula is

fz = 1000√(G/m) / 2π

For example, when spring stiffness is 100N/mm, a ball inertia of 50g corresponds to a natural frequency of approximately 225Hz; a ball inertia of 100g corresponds to a natural frequency of approximately 159Hz.

In hydraulic valves, there is often spring force acting on the spool. The situation is similar to the ball-spring system and will also cause vibration. The above formula can be referred to for estimating its natural frequency.

The ball-spring system is suspended in the air, and air resistance during vibration is small, so it will vibrate for a long time; the spool is installed in the valve body, and even without oil there will be valve body friction force, and vibration will weaken quickly.

When the valve body is filled with oil, the oil has elasticity and will still vibrate, only the natural frequency is different.

If the outlet of the spring chamber is made very small, it can produce a damping effect during vibration, and the vibration will settle relatively quickly.

If external force is repeatedly applied to a vibration system following its natural frequency, the vibration amplitude will become larger and larger (similar to swinging on a swing), which is called resonance (or sympathetic vibration) in engineering.

In actual systems, this situation may also occur when hydraulic pressure acts on the spool: the flow output by hydraulic pumps all has pulsation, and flow pulsation will cause pressure pulsation when encountering hydraulic resistance; pressure pulsation is a repeatedly acting external force, and if its frequency is the same as the valve’s natural frequency, it will cause resonance.

Not only when the frequencies are the same, but also when frequencies are close, it will affect amplitude.

If the valve’s natural frequency is fz, external force frequency is f, and external force amplitude is δ, then the ratio of spool amplitude δᵥ to external force amplitude δ is

δᵥ/δ = 1/|1 – f²/fz²|

From this, it can be known:

When external force frequency f is extremely low, spool amplitude δᵥ equals external force amplitude δ

When f is higher than fz, the higher f is, the smaller the effect of external force amplitude on spool amplitude

When f is close to fz, spool amplitude will be very large, and this situation should be avoided

Theoretically, when f=fz, resonance will occur and spool amplitude may be infinite, but this basically will not happen in practice – because:

High-performance systems require in-depth examination of their transient performance:

① How large will the overshoot be?

② Can it keep up with commands? How large will the delay be?

③ How long will it take to recover to steady state?