Menu

Hydraulic systems are found in vehicles, construction equipment, aircraft, manufacturing facilities, medical devices, home appliances, and entertainment venues. These systems use pressurized fluid to transmit power and control mechanical motion across virtually every industry and daily activity.

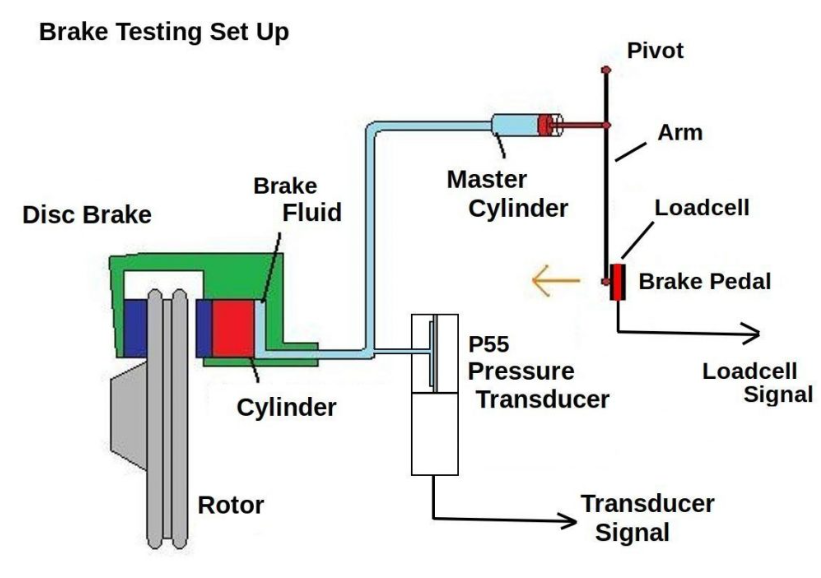

Modern automobiles contain multiple hydraulic systems working simultaneously. The braking system represents the most critical application—when you press the brake pedal, you activate a small piston in the master cylinder that pressurizes brake fluid throughout the system. This fluid travels through brake lines to wheel cylinders or calipers, where it forces brake pads against rotors to stop the vehicle. The hydraulic advantage amplifies your foot pressure by factors of 30 to 40 times.

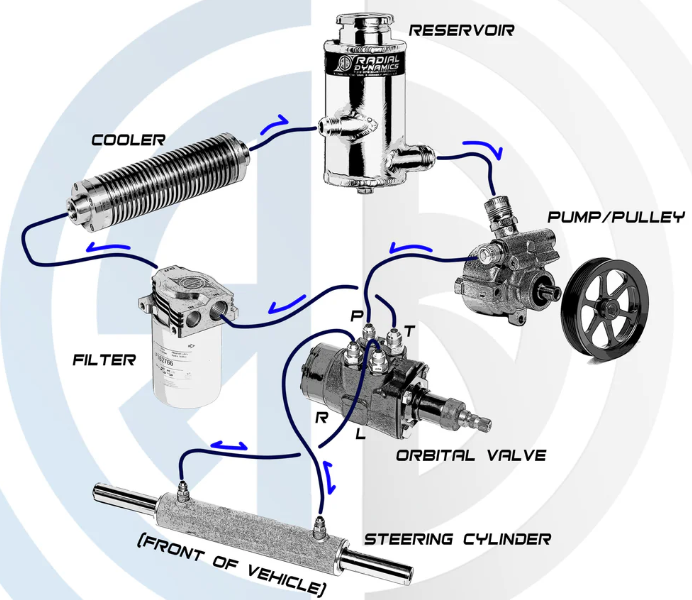

Power steering systems in many vehicles rely on hydraulic assistance. An engine-driven pump circulates pressurized fluid continuously through the steering mechanism. When you turn the wheel, control valves direct this pressurized fluid to either side of a steering cylinder, reducing the physical effort required to turn heavy front wheels. While electric power steering has gained popularity in newer models, hydraulic systems remain widespread in trucks and older passenger vehicles.

Automatic transmissions depend entirely on hydraulic pressure for operation. Unlike manual transmissions that use mechanical clutches, automatics employ a complex network of hydraulic valves, clutches, and servos. Transmission fluid acts both as a lubricant and as the medium for power transmission. The system adjusts hydraulic pressure to engage different gear sets, enabling smooth gear changes without driver input.

Suspension systems in luxury and performance vehicles often incorporate hydraulic or hydropneumatic technology. These systems can actively adjust ride height and damping characteristics. Citroën pioneered hydropneumatic suspension in the 1950s, a technology later adopted by Mercedes-Benz, Rolls-Royce, and other premium manufacturers. The system uses nitrogen-pressurized spheres connected to hydraulic circuits to provide superior ride comfort and automatic leveling.

Aircraft rely heavily on hydraulic systems for flight-critical functions. Commercial airliners typically run three independent hydraulic systems operating at pressures around 3,000 PSI. These systems control the landing gear deployment and retraction, enabling wheels to be lifted into the fuselage after takeoff and extended before landing. The hydraulic cylinders must handle substantial loads while operating reliably in extreme temperature conditions.

Flight control surfaces—including ailerons, elevators, rudders, and flaps—depend on hydraulic actuators for movement. At high speeds, aerodynamic forces on these surfaces can exceed several tons, making hydraulic assistance essential. Pilots’ control inputs trigger hydraulic valves that direct pressurized fluid to actuators, which then move the control surfaces with precision and power.

Aircraft braking systems use hydraulics to bring massive machines weighing hundreds of tons to a stop. The hydraulic brake system on a Boeing 777, for instance, generates enough force to stop the aircraft from landing speeds exceeding 150 knots. Anti-skid systems modulate hydraulic pressure to individual wheel brakes, preventing tire damage during heavy braking.

Space shuttles used hydraulic auxiliary power units as backup systems. Three independent hydraulic systems provided power for flight control, landing gear operation, and other critical functions during launch, orbit, and landing phases.

Ships and submarines incorporate hydraulic systems throughout their design. Steering systems on large vessels use hydraulic ram actuators connected to the rudder. These systems can exert the tremendous force needed to turn ships displacing tens of thousands of tons through water.

Ballast control systems use hydraulic pumps and valves to manage water distribution throughout the vessel. Submarines particularly depend on precise ballast control for depth management and stability. Hydraulic systems enable rapid flooding or emptying of ballast tanks, allowing submarines to dive, surface, or maintain specific depths.

Cargo handling equipment on ships—including cranes, winches, and hatch mechanisms—operates hydraulically. Container cranes in ports can lift loads exceeding 60 tons, made possible through high-pressure hydraulic circuits. Anchor windlasses and mooring equipment also utilize hydraulic motors for reliable operation in harsh maritime environments.

Excavators represent one of the most hydraulic-intensive machines in construction. A typical excavator contains multiple hydraulic circuits controlling the boom, stick, bucket, swing function, and travel motors. The machine’s hydraulic system can operate at pressures up to 5,000 PSI, enabling a 20-ton excavator to dig through rock and lift loads several times its own weight.

Bulldozers use hydraulics for blade control and ripper operation. The blade can be angled, tilted, and raised or lowered through independent hydraulic cylinders. This precise control allows operators to grade surfaces with inch-level accuracy. Track-type dozers also employ hydraulic final drives that convert engine power into track movement.

Backhoe loaders combine hydraulics for both excavating and loading functions. The rear digging assembly operates through a series of hydraulic cylinders, while the front loader bucket uses separate hydraulic circuits. This dual functionality makes backhoes among the most versatile construction machines, commonly found on job sites worldwide.

Cranes depend entirely on hydraulics for lifting capacity. Mobile cranes use hydraulic cylinders to extend and retract boom sections, while hydraulic motors drive the hoist mechanism. Tower cranes, though often electrically powered for hoisting, use hydraulics for trolley movement and boom luffing. The largest mobile cranes can lift over 1,200 tons, with hydraulic systems precisely controlling load movement.

Forklifts utilize hydraulics for mast operation and lifting functions. The hydraulic system raises the load carriage along vertical rails, while tilt cylinders allow the mast to lean forward or backward. Outdoor forklifts operating in rough terrain conditions particularly benefit from hydraulic systems’ ability to function reliably in harsh environments with contamination and temperature extremes.

Aerial work platforms and cherry pickers employ multiple hydraulic cylinders for boom extension and platform positioning. These machines must safely elevate workers and equipment to heights exceeding 100 feet while maintaining stability. Hydraulic systems provide the smooth, controlled motion necessary for safe operation at elevation.

Asphalt pavers use hydraulics for screed height control and material distribution. The screed, which spreads and levels asphalt, adjusts its position through hydraulic cylinders responding to automatic grade controls or manual operator input. This precision enables road surfaces to meet strict flatness specifications.

Road rollers and compactors employ hydraulic drive systems for their drums. Vibratory rollers use hydraulics to create the oscillating force that compacts soil and asphalt. The ability to adjust vibration frequency and amplitude hydraulically allows operators to optimize compaction for different materials.

Snowplows and street sweepers incorporate hydraulic systems for blade positioning and angle adjustment. Snowplow blades can be raised, lowered, angled left or right, and tilted through independent hydraulic controls. This versatility enables operators to clear roads efficiently in varying snow conditions.

Hydraulic presses form the backbone of metal fabrication, capable of exerting forces from 20 tons to over 10,000 tons. These machines stamp, form, bend, and shape metal components through controlled hydraulic pressure. Automotive manufacturers use massive hydraulic presses to stamp body panels, fenders, and structural components from flat steel sheets.

Press brakes utilize hydraulic cylinders to bend metal sheets with precision. The synchronized operation of multiple hydraulic cylinders ensures even force distribution across the full width of the bend. Modern CNC press brakes achieve angle accuracy within 0.5 degrees through precise hydraulic pressure control.

Forging operations employ hydraulic presses to shape heated metal billets into complex forms. The ability to control press speed and dwell time makes hydraulics ideal for forging, where material flow must be carefully managed. Some forging presses operate at pressures exceeding 15,000 PSI to work with high-strength alloys.

Metal shears and punches use hydraulic power to cut through thick steel plates. A hydraulic punch press can create hundreds of holes per minute in sheet metal, with hydraulic systems providing consistent force throughout each punching cycle.

Conveyor systems in warehouses often incorporate hydraulic lifts and tilters. Package sortation facilities use hydraulic diverters to route items to different lanes. These systems must operate continuously with minimal maintenance, making hydraulics’ reliability particularly valuable.

Dock levelers bridge the gap between loading docks and truck beds, using hydraulic cylinders for raising and lowering. When a truck backs up to a dock, the leveler hydraulically adjusts to match the truck bed height, enabling smooth material transfer via forklifts or pallet jacks.

Automated storage and retrieval systems (AS/RS) in modern warehouses employ hydraulic lifts to move pallets vertically. These systems can stack pallets in high-bay warehouses exceeding 100 feet tall, maximizing storage density while maintaining rapid retrieval times.

Injection molding machines depend on hydraulics for both clamping and injection functions. The hydraulic clamping system holds mold halves together against injection pressures that can exceed 2,000 bar. Clamping forces on large machines may reach 4,000 tons, requiring massive hydraulic cylinders.

The injection unit uses hydraulic pressure to force molten plastic into mold cavities. Precise control of injection pressure and speed proves critical for producing quality parts without defects. The hydraulic system must rapidly switch from high-speed injection to controlled pressure holding phases.

Blow molding equipment for bottles and containers uses hydraulics for mold closing and extruder operation. The system coordinates multiple functions—parison extrusion, mold closing, blow air injection, and part ejection—all under hydraulic control.

Modern farm tractors feature extensive hydraulic systems controlling implements and attachments. The three-point hitch system uses hydraulic cylinders to raise and lower mounted equipment like plows, cultivators, and seeders. Draft control systems automatically adjust implement depth based on load sensing through hydraulic pressure.

Hydraulic remote valves on tractors allow operators to control external hydraulic cylinders on implements. A typical tractor provides 2-6 sets of remote hydraulic connections, enabling simultaneous control of multiple functions on complex implements. Hydraulic flow rates can exceed 100 liters per minute on high-capacity tractors.

Front-end loaders mounted on tractors operate entirely through hydraulics. Two lift cylinders raise the loader arms, while a bucket cylinder controls bucket angle. The loader’s parallel-lift design, achieved through precise hydraulic cylinder placement, keeps loads level throughout the lifting range.

Combine harvesters integrate numerous hydraulic functions. The header reel height adjusts hydraulically based on crop conditions. Hydraulic motors drive the threshing cylinder and separation systems. The unloading auger extends and rotates under hydraulic power, allowing grain transfer to trucks while harvesting continues.

Forage harvesters and cotton pickers use hydraulic systems for header positioning and crop processing functions. The ability to adjust machine settings on-the-go through hydraulic controls increases productivity by eliminating adjustment downtime.

Grape harvesters employ hydraulic shakers that vibrate vines to dislodge fruit. The shaking frequency and amplitude can be hydraulically adjusted for different grape varieties and vineyard conditions, minimizing vine damage while maximizing harvest efficiency.

Center-pivot irrigation systems use hydraulic motors to drive wheeled towers across fields. Each tower progresses at a controlled rate, ensuring uniform water application. Hydraulic systems also control end guns and drop spans that extend or retract based on field boundaries.

Hydraulic-powered pumps draw water from wells, rivers, or canals for irrigation distribution. These pumps can move thousands of gallons per minute, with hydraulic controls enabling remote operation and automated scheduling. Variable-speed hydraulic drives optimize energy consumption based on water demand.

Hospital beds incorporate hydraulic systems for height adjustment, backrest positioning, and bed articulation. Manual hydraulic systems use foot-operated pumps to raise or lower the bed, while electro-hydraulic versions employ electric motors driving hydraulic pumps. The height adjustment range typically spans 18-30 inches, enabling ergonomic working heights for medical staff.

Trendelenburg and reverse Trendelenburg positioning—where the entire bed tilts head-down or feet-down—relies on hydraulic actuators. These positions assist with surgical procedures and patient recovery. The hydraulic system must hold position securely, with fail-safe mechanisms preventing unintended movement.

Bariatric beds designed for patients exceeding 600 pounds require robust hydraulic systems. These specialized beds use high-capacity hydraulic cylinders and reinforced frames to safely support and position heavy patients.

Surgical tables employ sophisticated hydraulic systems for precise patient positioning. Electro-hydraulic actuators enable lateral tilt, Trendelenburg positioning, height adjustment, and flexion/extension of table sections. Neurosurgery and orthopedic procedures particularly demand precise positioning capabilities.

C-arm imaging systems use hydraulic counterbalancing to help radiographers easily position the imaging equipment around patients. The hydraulic system supports the C-arm’s weight while allowing smooth manual repositioning. Some advanced systems incorporate hydraulic brakes that automatically engage when released.

Operating room lights mounted on hydraulic arms can be positioned anywhere in the workspace. The hydraulic counterbalance supports the light head’s weight while allowing effortless movement. Spring-assisted hydraulic systems maintain position through friction, requiring no locks or power.

Ambulance stretchers utilize hydraulic systems for load assistance. When loaded into the ambulance, stretcher legs fold automatically as hydraulic dampers control the lowering rate. Loading patients requires minimal physical effort from paramedics, reducing injury risk.

Hydraulic pumps on stretchers enable field height adjustment without electrical power. Paramedics can raise stretchers to working height for patient care and assessment, then lower them for transport. The manual hydraulic system remains functional even when the ambulance’s electrical system is compromised.

Patient transfer devices in hospitals use hydraulic lifts to move individuals between beds, wheelchairs, and other surfaces. Ceiling-mounted hydraulic patient lifts allow caregivers to transfer patients safely without manual lifting, protecting both patients and staff from injury.

Roller coasters incorporate hydraulics in multiple systems. Launch coasters use hydraulic actuators to accelerate cars from 0 to 100+ mph in under 4 seconds. The hydraulic system rapidly extends a cable that pulls the coaster train, delivering acceleration forces exceeding 4 Gs.

Track-switching mechanisms on coasters operate hydraulically, enabling rapid changes in train routing. The hydraulic actuators must move heavy steel track sections quickly while maintaining precise alignment—positioning accuracy within millimeters proves essential for safe operation.

Ride safety restraints employ hydraulic cylinders for automated lowering and locking. When a ride begins, hydraulic pressure locks restraints in position. Multiple redundant hydraulic circuits ensure restraints cannot release during operation, even if one circuit fails.

Drop towers use hydraulic systems or combinations of hydraulic and magnetic braking. After a free-fall drop, hydraulic brakes smoothly decelerate the ride vehicle, providing a controlled stop that’s thrilling yet safe. The hydraulic system can adjust braking force based on vehicle weight and weather conditions.

Stage lifts in theaters raise and lower sections of the stage floor. Large venues may have dozens of individual lift sections, each controlled by hydraulic cylinders. The Metropolitan Opera House in New York features hydraulic stage lifts capable of raising entire set pieces and performers 20 feet above or below stage level.

Orchestra pits use hydraulic platforms that can be lowered for musical performances or raised to stage level to increase performance space. The hydraulic system must operate quietly during performances—acoustic isolation of pumps and motors proves critical in theater applications.

Automated rigging systems increasingly employ hydraulic winches for raising and lowering scenery, lighting, and acoustical shells. Hydraulic systems provide precise position control and can safely handle loads exceeding 10,000 pounds. The system’s variable speed capabilities enable smooth motion for moving scenic elements during live performances.

Camera cranes and jibs in film production use hydraulics for smooth, controlled camera movement. The hydraulic system counterbalances the camera’s weight while allowing camera operators to create fluid motion. Hydraulic damping reduces vibration that would otherwise create shaky footage.

Motion simulators for special effects sequences rely on hydraulic actuators. These systems can reproduce vehicle motion, turbulence, and impact effects while actors perform in front of green screens. Industrial-grade hydraulic actuators provide the force and speed necessary to create convincing motion effects.

Hydroelectric dams use massive hydraulic gates for water flow control. The gates, often weighing hundreds of tons, raise and lower through high-capacity hydraulic cylinders. Tainter gates—common in dam spillways—pivot on hydraulic actuators to regulate water release during flood conditions.

Turbine control systems employ hydraulic actuators for wicket gate and runner blade adjustment. These components control water flow through the turbine, optimizing power generation across varying water flow rates. The hydraulic control system responds in milliseconds to load changes, maintaining stable power output.

Penstock valves that isolate turbines for maintenance operate hydraulically. These valves must close against significant water pressure while handling flows measured in thousands of cubic feet per second. The hydraulic operating system includes accumulators that store energy for emergency closure.

Wind turbines incorporate hydraulic systems for blade pitch control and yaw drive operation. The pitch system rotates blades around their longitudinal axis to optimize power capture or limit speed in high winds. Three independent hydraulic systems—one per blade—ensure redundancy in the pitch control system.

Hydraulic braking provides fail-safe shutdown capability. If electrical systems fail or wind speeds exceed design limits, hydraulic brakes engage automatically to stop rotor rotation. The hydraulic accumulator stores sufficient energy to deploy brakes multiple times without external power.

Nacelle yaw systems use hydraulic motors to orient the turbine into the wind. The yaw drive must overcome substantial forces—a 3 MW turbine’s nacelle can weigh over 70 tons. Hydraulic systems provide the high torque needed to rotate this mass slowly and smoothly.

Drilling rigs employ hydraulic systems for draw works, pipe handling, and blowout preventer (BOP) operation. The BOP hydraulic system represents a critical safety feature, capable of shearing and sealing drill pipe to prevent well blowouts. BOP hydraulic systems operate at pressures up to 5,000 PSI with multiple backup systems.

Hydraulic fracturing pumps inject fluid into underground formations at pressures exceeding 10,000 PSI. Multiple high-pressure hydraulic pumps operate in parallel, collectively delivering flow rates of 100 barrels per minute or more. The extreme pressures and continuous operation demand robust hydraulic components.

Pipeline operations use hydraulic actuators to control valves throughout the distribution network. In emergency situations, hydraulic systems can close isolation valves in seconds, limiting potential spills or pressure releases.

Office chairs utilize gas springs that function on hydraulic principles—though technically pneumatic, they work similarly by using compressed gas instead of liquid. The chair height adjustment lever releases gas pressure, allowing the chair to lower or raise based on the occupant’s weight.

Standing desks with hydraulic adjustment mechanisms provide smooth height transitions. The hydraulic cylinder system balances the desktop weight, requiring minimal force for adjustment. Some models incorporate dual hydraulic columns for wider desktops and increased weight capacity.

Reclining furniture employs hydraulic dampers for controlled motion. The dampers prevent the chair from springing upright when the occupant shifts weight, instead providing gradual, controlled return to upright position.

Vehicle lifts in repair shops use hydraulic cylinders to raise cars 6-8 feet off the ground. Two-post and four-post lifts rely entirely on hydraulics, with safety locks engaging at specific height intervals. These lifts can handle vehicles weighing up to 18,000 pounds.

Floor jacks for tire changes operate through hydraulic pressure generated by pumping the handle. The hydraulic cylinder extends, raising the jack saddle and the vehicle. A release valve allows controlled lowering by metering hydraulic fluid back to the reservoir.

Tire changing machines use hydraulic systems for bead breaking and mounting/dismounting operations. The hydraulic pressure applies controlled force to separate the tire bead from the wheel rim without damaging either component.

Garbage trucks incorporate some of the most visible hydraulic applications in urban environments. The compaction system uses hydraulic cylinders to crush refuse, reducing its volume by 80-90%. A typical rear-loading garbage truck can compact 30 cubic yards of loose trash into about 12 cubic yards of compacted waste.

Front-loading commercial waste trucks use hydraulic forks to lift dumpsters overhead and empty them into the truck hopper. The hydraulic system lifts loads exceeding 3,000 pounds repeatedly throughout the collection route. The automated lifting mechanism eliminates manual handling, improving worker safety and collection speed.

Waste compactors at landfills employ hydraulic systems in crawler tractors that spread and compress refuse. The hydraulic-driven blade pushes waste into place while hydraulic cylinders control blade angle and tilt for optimal material movement.

Construction and heavy equipment sectors represent the largest users of hydraulic systems, followed by manufacturing, agriculture, and transportation. The global hydraulics market was valued at $44.08 billion in 2024, with construction equipment accounting for approximately 19% of market share. Material handling and agricultural applications each represent significant portions of hydraulic system demand, particularly as automation increases in these sectors.

Hydraulic systems demonstrate exceptional reliability when properly maintained, particularly in aerospace and medical applications where failure isn’t acceptable. Aircraft hydraulic systems incorporate triple redundancy, with each system capable of independent operation. Properly maintained hydraulic systems in industrial settings commonly achieve 20-30 years of service life. The sealed nature of hydraulic components protects internal parts from contamination and wear, contributing to longevity. Regular fluid analysis and seal replacement prevent most failures before they occur.

While electrification continues advancing, hydraulics remain essential where high power density and force requirements exist. The hydraulics market projects growth to $57.61 billion by 2032, driven by construction, agriculture, and industrial automation expansion. Electric actuators have gained ground in precision positioning and lighter-duty applications, but heavy equipment continues favoring hydraulics for power density advantages. Hybrid electro-hydraulic systems increasingly combine both technologies’ strengths—electric control with hydraulic power.

Hydraulic systems function across temperature extremes from -65°F to over 400°F with appropriate fluid selection. Arctic equipment uses specialized low-temperature hydraulic fluids, while steel mill applications employ fire-resistant fluids rated for high temperatures. The sealed design protects hydraulic systems from dust, moisture, and contamination that would compromise other technologies. Marine hydraulic systems operate successfully in corrosive saltwater environments with proper corrosion-resistant materials and protective coatings.

Market size and growth data: MarketsandMarkets Research (2024-2025 hydraulics market reports), Straits Research (2024), Mordor Intelligence (2025), Data Bridge Market Research (2025)

Industry applications: Brennan Industries technical documentation, Power & Motion Technology industry analysis, International Trade Administration data

Technical specifications: Bosch Rexroth hydraulic systems documentation, Parker Hannifin technical resources, Danfoss product specifications