Menu

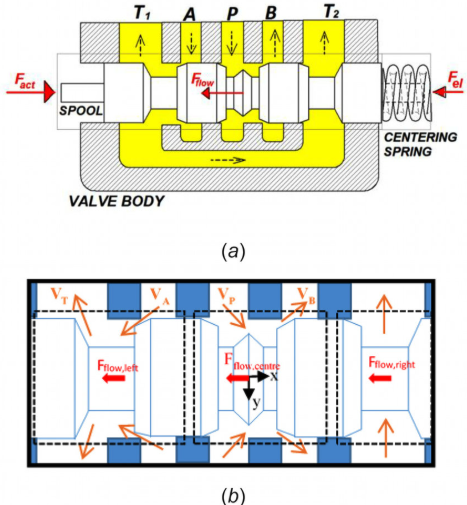

As mentioned earlier, when the pressure difference is fixed, what determines the flow through the passage is the opening size and viscosity. All hydraulic valves achieve their required functions by moving (including rotation) the valve spool within the valve body to change the shape and/or opening size of the flow passage.

So how can we move the valve spool to make it reach the desired position and achieve the required opening?

The valve spool is a mechanical component, a fellow that only recognizes force. It obeys, and only obeys, the principle of force balance:

If all the forces acting on it are balanced, it stops and remains stationary.

If all the forces acting on it are unbalanced, it will move.

Generally speaking, what force controls the movement of the valve spool determines the valve’s function; what resistance forces it encounters and how it moves determines the valve’s performance.

Therefore, to master a valve, in addition to understanding the valve’s structure and opening, it is particularly important to examine: what forces are controlling and obstructing the axial movement of the valve spool, and how does the valve spool move? As mentioned in the previous chapter, common spool valves and poppet valves both rely on axial movement to complete their functions during operation. Therefore, the first concern is the forces affecting the axial movement of the valve spool.

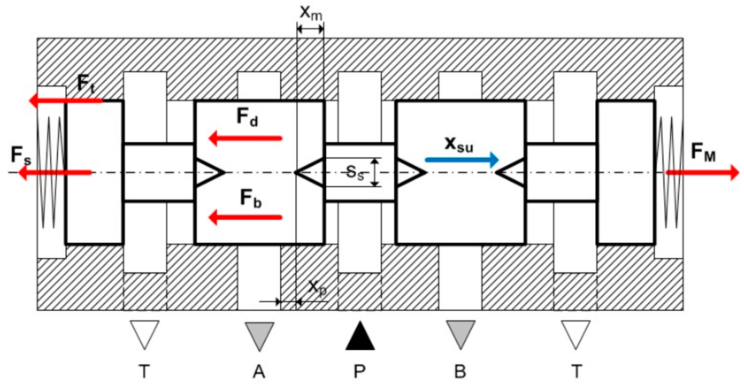

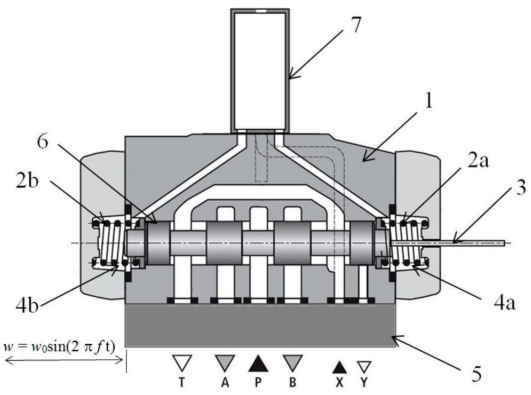

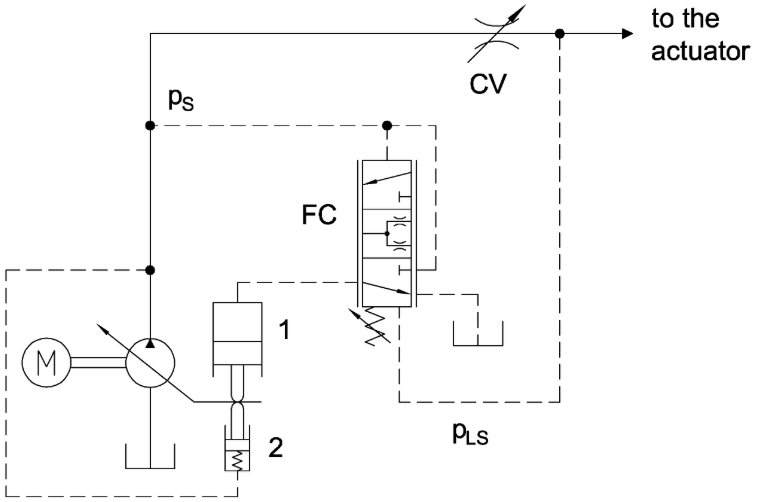

Figure 4-1 summarizes all the control forces and resistance forces affecting the axial movement of the valve spool. Generally divided and broadly speaking, they are roughly as follows.

Moving the valve spool encounters resistance forces. Although undesirable, the following types are unavoidable:

Static pressure force refers to the working condition where the oil relative to the acting surface has no macroscopic flow, or the flow velocity is very small and its effect can be ignored. In this case, the pressure of the oil on these surfaces conforms to Pascal’s principle — equal everywhere. If these forces are unbalanced, they become resistance forces affecting the valve spool’s operation. If handled properly, they become assisting forces, namely various hydraulic actuation, also called hydraulic control: such as pilot valves, differential pressure valves, etc.

Hydraulic forces are additional forces generated when oil flows relative to the valve spool’s acting surface. Hydraulic forces are generally not large; therefore, they only have a noticeable impact on the working range of electromagnetic directional control valves, the flow-pressure characteristics of relief valves, and the regulation of electrohydraulic proportional valves, and need to be examined and studied.

Friction force is related to the valve spool’s movement speed, affected by various factors, and influences the valve’s regulation performance. Friction force is very complex and difficult to calculate accurately, but it can be controlled.

Most valves contain springs, usually installed in the valve in a pre-compressed form. The preload force is set artificially, reflecting the intention of the valve manufacturer or user, and is fixed when the valve spool has not moved. However, because the valve spool needs to move during operation, the spring force generally changes accordingly, often bringing undesirable side effects. So to speak, the spring doesn’t help for free, which is something valve designers should anticipate.

Valve spools all have mass; therefore, all valve spools used on Earth and near Earth are affected by gravity. However, most valve spools have a mass not exceeding 100g, so the gravity they experience does not exceed 1N. Compared with other forces in modern hydraulics, this is generally small enough to be ignored. Therefore, modern hydraulic valves can generally be installed in any direction without considering the influence of gravity, and their performance is basically unaffected. However, the mass of the valve spool cannot be ignored! Because the mass of the valve spool leads to the inertia of the valve spool, and inertia will slow down the change of motion state, somewhat like a resistance force, so it is often called inertial force. In fact, its obstruction to object motion is essentially different from friction force, spring force, etc.: inertia does not affect the resultant force. The inertia of the valve spool will affect the valve and even the dynamic characteristics and transient response of the entire system (see Section 4.9 Transients for details)!

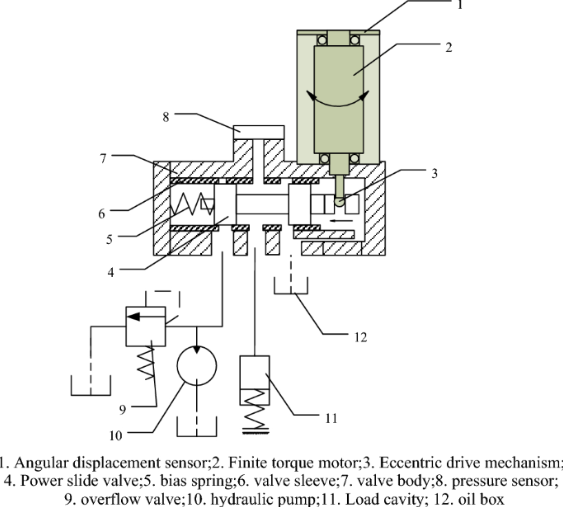

Control forces are intentionally arranged and reflect the operator’s intention. They can be roughly divided into external control and internal control.

External control forces refer to forces introduced from outside the valve to move the valve spool.

Controlled through handles, handwheels, foot pedals, etc.

Driven by a moving component in the machinery.

Internal control forces refer to forces acting on the valve spool inside the valve.

Driven by the pressure of compressed air.

Driven by oil pressure, also called hydraulic actuation.

Controlled and driven by solenoids, torque motors, stepper motors, servo motors, etc. mounted on the valve, also called electric actuation.

Electric control has two meanings in this book: the broad meaning is the control of various components in the system, including pumps, motors, electric motors, etc. In this chapter, it is narrow, specifically referring to the control of the valve spool.

In fact, the actual magnitude of the control force is often determined by the resistance force.

Moving the valve spool encounters all resistance forces, combined together, generally speaking, usually do not exceed a few hundred N. If the control force can be very large, sufficient to overcome the resistance, and the requirements for time and accuracy are not high, there is no need to pay much attention.

For manual operation, valve designers generally set up lever mechanisms based on experience to enable operators to control effortlessly. Because human muscle force can have a very large range of variation, if the resistance occasionally increases for some reason, the operator only needs to exert a little more force, at worst using all their strength, and can always control it.

The driving force of mechanical actuation is even less of a problem.

As for electric control, due to the limitations of volume and power on electric actuators, the output force is often small and may not be sufficient to directly overcome the resistance. In this case, pneumatic or hydraulic assistance is needed.

Hydraulic assistance can generate sufficiently large forces and generally needs to be pressure-reduced in actual use.

Being able to grasp these forces enables one to control the valve’s performance. The extent to which one can predict and control these forces, especially those undesirable but unavoidable resistance forces, reflects the level of the valve designer and manufacturer. Whether the manufactured valve is well-behaved and obedient depends on whether the designer and manufacturer can grasp these forces. Generally speaking, the control force determines the valve’s function — what it can do, while the combined effect of control force and resistance force determines the valve’s performance — how well it does it.